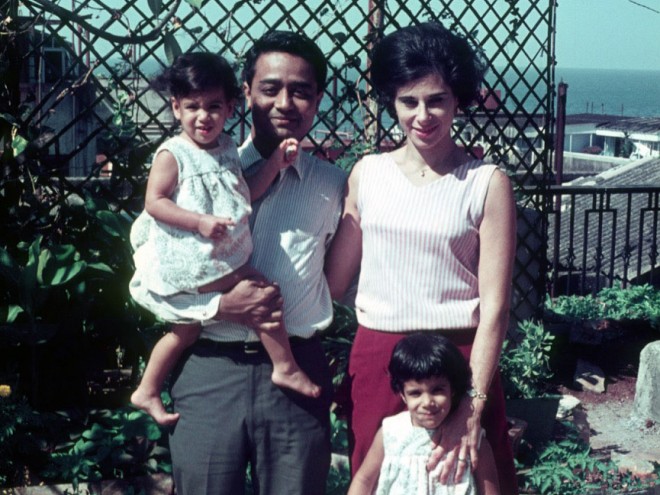

Photo courtesy of the author

With one thousand dollars in her pocket, my mother went on a European tour in June 1957, when she was twenty-three years old. She took a ferry to England and caroused across several continents. Her parents kept fifty pages of letters she wrote to them during this time, which tell a story of the writer she could have been had she lived the life she expected. She went on to teach in New York City for ten years, before giving up this job when she met my very handsome father. They shipped off to upstate New York where he had a job, and then she moved with him and my older sister to Germany for seven months and finally to India for seven years.

During that time, she became less sure of herself. While in Bombay she taught some, but not enough, and eventually became depressed. By the time she returned to the States, in 1973, her teacher certifications were outdated and she couldn’t get a job in New Jersey after being out of full-time teaching for so long. She settled into her domestic life, wrote a few incisive articles on art, taught herself to become a pro cook, listened to the radio, obsessed over the O.J. Simpson trial, decorated, gardened, took my sister and I to plays, art exhibits, the symphony, and the opera.

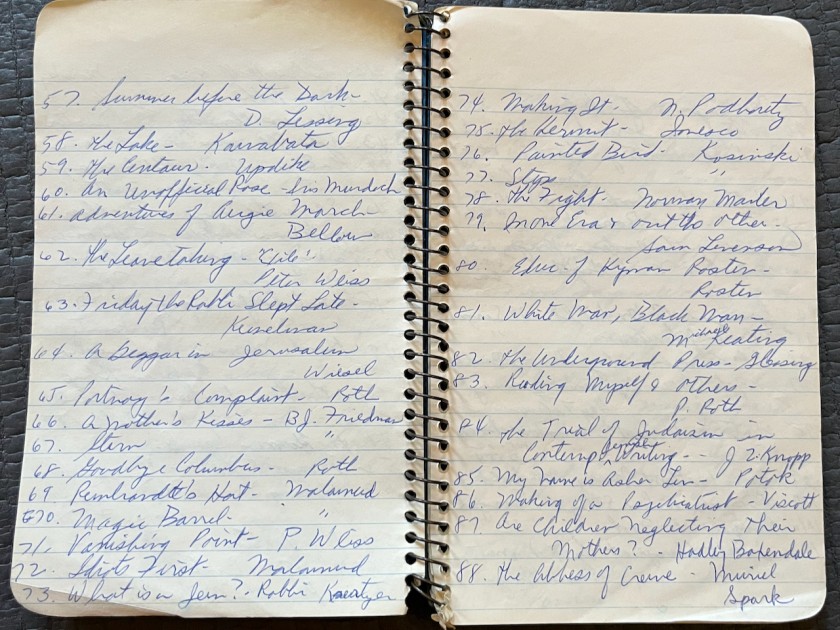

Eventually, she began teaching English as a second language to Russian Jewish immigrants she met in New Haven, Connecticut, and that seemed to sustain her. But what really kept her going were books. The year after she returned to the States, she started a notebook listing the books she read from 1974 to 1985. So many are Jewish authors — she wouldn’t just dip in, but would go on a kick and read their entire oeuvre. Here are entries fifty-seven through seventy-three:

The Summer Before the Dark, Doris Lessing

The Lake, Yasunari Kawabata

The Centaur, John Updike

An Unofficial Rose, Iris Murdoch

Adventures of Augie March, Saul Bellow

Leavetaking, Peter Weiss

Friday the Rabbi Slept Late, Harry Kemelman

A Beggar in Jerusalem, Elie Wiesel

Portnoy’s Complaint, Philip Roth

A Mother’s Kisses, Bruce Jay Friedman

Stern, Bruce Jay Friedman

Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth

Rembrandt’s Hat, Bernard Malamud

The Magic Barrel, Bernard Malamud

Vanishing Point, Peter Weiss

Idiots First, Bernard Malamud

What is a Jew? Rabbi Morris N. Kertzer

She read sleuthing and literary books, and seemed to be searching for a sense of what it meant to be Jewish after living in places where it was rare or problematic to be so. She had an electric intellect, and if she had not become so depressed, she would have made a great critic. Judging by the books she read, I believe she had a shot at producing a family novel written with verve, attitude, and wit. I like to think that she wrote those books into her mind and they fit her personality and saved her life. Malamud and Roth, it turned out, became writers I loved, too.

Author’s mother on May 30,1954, age twenty

My perception of my mother has changed over the course of the twenty-three years since she died. Something shifted after I read the unfettered and eloquent letters she wrote while touring Europe and experiencing the fullness of an independent life for the first time. She had an easy, informal style and a psychological acuity that is rare for a young writer, but it is her startling exclamations, as she sailed into a new life, that altered my connection to her. Here are some of those letters — a novel, in my mind.

Nice, Sunday

Oh, is this magnificent country. You two would absolutely revel in this climate and scenery. We got to Nice two hours late because of some accident on the way between two other trains. Well, the last few hours on the train were wonderful because we role all along the coast, from Marseilles to Nice. Tall, waving palm trees, a beautiful sea, and an irregular coast line were breathtaking. I’m sitting in a park now right off the famous Promenade des Anglais, which runs along the Mediterranean for miles. Went swimming yesterday; the water was an emerald green; and just the perfect temperature. Had a Jewish supper last night — real chopped liver. What a city Nice is. The shops everywhere are expensive and luxuriously beautiful. It’s not a commercial tourist town, like other places I’ve seen, even though the joint is hopping with Americans. The hotels are mostly white, not more than five stories and nothing as showy as in Las Vegas. It’s really all it’s “cracked up to be.” The sun is hot and it stays out till about 8 at night. Today we relax on the rocky beach; tomorrow to Cannes and Antibes. Tuesday to Monaco, and Wednesday we’ll see. Probably leave here Wednesday night or Thursday.

Only a Brooklyn girl would be this excited to find chopped liver. What’s unusual is the way she starts and ends this paragraph — “Oh” and then the inversion, with the verb first. Everything is recorded — the accident between two other trains is barely mentioned before she moves on. It is a delicate and writerly way of telling more of the story than we will ever know. The wreck happens quietly in the background, just as Mrs. Ramsey dies and World War I comes and goes in Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, and similar to the way that in Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon, polite conversation is happening at the table but World War II has arrived.

Here is a second passage, on her way out of Sweden, that feels like the funny-true stereotypes that Roth knots himself into. She was glad to be rid of the Swedes, who she found “too passive, dull, uninteresting, and phlegmatic. Not intellectual at all.” As she planned her trip to Berlin, she had a few ideas about Germans:

What other people don’t do when traveling the Germans know how to do. They’re always on the go; they deprive themselves of almost all food save black bread, cheese, or butter and bread; and, of course, milk. They go by bicycle over places that others find too difficult to traverse. They never feel sorry for themselves.”

For a while, she loved Ernest Hemingway and said she ate up all of his books. I remember her talking about seeing the bullfights. She didn’t tell me the whole story, and she sensed the oppression there:

I abhor seeing the varieties of uniforms all about me — on the trains, the streets, the buses, the restaurants, the theatres, the hotels, the beaches…I’m losing interest in things Spanish you can see. Another thing too: in Valencia, I went with my Dutch friends to a big bull fight at their grand Plaza de Toros. You can imagine my excitement at seeing one at long last, since it’s something that’s intrigued me for a long time — ever since reading Hemingway. Another letdown! Brutal, blood, and just ridiculously futile…why??? “Why” is all I could say after it was all over. All the pomp and glory became tragically absurd to me. You should have seen the excitement, the mobs of people scurrying about after it ended. It looked like a wild passion-ridden mob racing about all around the large plaza. We were literally swept along with the crowd.

The other fifty pages of her letters are a riot, full of snark, joy, and exclamatory moments of welcomed experience, dinner with foreigners, visits to museums, sitting in on a murder trial, riding a motorcycle, browning on beaches, and going to bakeries to collect her beloved French bread, butter, and milk. She stayed in hostels, learned Swedish and collected Berlitz books, went to Shakespeare plays and Wagner operas, befriended everyone, vomited off the side of the steamer. She created a traveler’s tale, a comic novel in letters, a chronicle of a hostel-to-hostel journey in the 1950s; she raged about the state of America, and felt buoyed talking politics or philosophy and going on dates. She thought about going on the lecture circuit. Life did not get in her way.

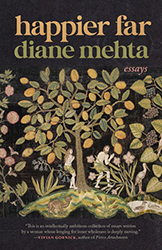

Happier Far by Diane Mehta

Diane Mehta was born in Frankfurt, grew up in Bombay and New Jersey, studied in Boston, and now makes her home in New York City. Her second poetry collection Tiny Extravaganzas is out with Arrowsmith Press on Oct 15, 2023. Her essay collection Happier Far comes out in 2024. New and recent work is in The New Yorker, Virginia Quarterly Review, Kenyon Review, American Poetry Review, and A Public Space. Her writing has been recognized by the Peter Heinegg Literary Award, the Café Royal Cultural Foundation, and fellowships at Civitella Ranieri and Yaddo. She was an editor at A Public Space, PEN America, and Guernica. Her latest project is a poetry cycle connected to The Divine Comedy. She is also collaborating with musicians to invent a new way of working through sound together.