Language and witnessing are inextricably linked. The world changes, and in turn, our words change with it. With each passing year, new slang is added into our collective lexicon; one can even tell somebody’s age by the kinds of words and phrases they use, the songs they sing, the events and trends they reference.

Now take this concept and place it within the context of catastrophe. How does collective trauma inform the words, phrases, and ideas we use in our daily lives? We saw this with the coronavirus pandemic: suddenly, our daily conversations included vocabulary such as “social distancing,” “KN95 masks,” and “I got the ’rona” (that one courtesy of TikTok). Our lives were entirely different from what they had been just months earlier. And our conversations, our understanding of the shared experience we are all going through in the wake of the pandemic, are still very much in flux, changing every day.

______

Occupied Words: What the Holocaust Did to Yiddish by Hannah Pollin-Galay examines the phenomenon known as Khurbn Yiddish (“Destruction Yiddish”) through archival work conducted from within the ghettos and camps, academic philosophies and scholarship, and creative writing. The book chronicles the various efforts made during and after the war to monitor and analyze the changing Yiddish language.

What is Khurbn Yiddish, exactly? During the Holocaust, Jews in occupied regions were subjected to unfathomable brutality, suffering, and inhumanity. Many felt that prewar Yiddish did not have the capacity to accurately convey their new reality; what words could possibly describe the conditions of the ghetto, the way Nazi officers treated Jewish prisoners, and the destruction of an entire culture? Thus, the language changed along with the people who spoke it. New words and phrases were coined, old words and phrases were repurposed with new meanings, and smatterings of German, Polish, and other languages found their way into Yiddish vocabulary. One prime example is the verb organizirn. Before the war, this word meant what one would expect — to organize. But during the war, it took on a new meaning — to steal from other prisoners. To “organize” goods for one’s own survival. The very nature of this word changed depending on who used it, and in what context. Sometimes, “organizing” was seen as a negative act, and sometimes it was considered “a synonym for activism, courage, respectability … ”

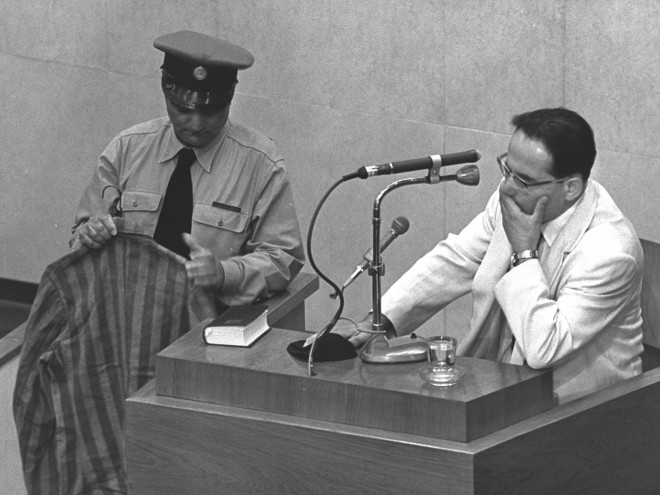

Pollin-Galay looks at the various ways in which this new form of Yiddish was recorded, categorized, and recollected by highlighting a number of lexicographers and writers, noting how the use and purpose of Khurbn Yiddish differed for each. The lexicographers — Nachman Blumental, Elye Spivak, and Israel Kaplan — all had different approaches to their study of Khurbn Yiddish, but each made invaluable contributions to our understanding of the language’s progression and lasting impact on Holocaust memory. Blumental believed that “peoplehood depended on language,” and through that, not through biology or ethnicity, were Jewish survivors connected. Spivak focused on the productivity of language, how it can give way to political and cultural change. Kaplan employed the use of humor and sarcasm to find agency in the face of Jewish suffering and demoralization. Meanwhile, the writers K. Tzetnik and Chava Rosenfarb folded Khurbn Yiddish into their personal writing. K. Tzetnik — whose pen name is derived from the Khurbn Yiddish word for “prisoner” — was rebellious with his use of the language. He utilized Khurbn Yiddish as a means of protest, of refusing to return to normalcy. In contrast, Chava Rosenfarb was focused on the communal impact of the language. She incorporated Khurbn Yiddish into her poetry and prose as a way to demand responsibility from witnesses to the Holocaust — both survivors and bystanders — as well as to influence future generations to “overcome [their] apathy and ‘teach people how to love.’”

Not everyone supported the use of Khurbn Yiddish; some people thought it an ugly language, an extension of the opinion that Yiddish was simply a lowbrow offshoot of German or an uncultured alternative to Hebrew. Why pepper the language of victims with Nazi-uttered words? Why permanently alter Yiddish to reflect the tragedy so many were trying to forget?

Occupied Words masterfully assesses how the meaning of the words we use changes based on context. Weaving Khurbn Yiddish words into the text, Pollin-Galay demonstrates the evolution of the Yiddish language as if in real time. Her use of sources from the twentieth century to the present reminds us that, just as language is ever-changing, so too is our discourse surrounding it. The book emphasizes that we must bear witness to the events happening in the world around us in whatever way we are able. They should impact how we speak, how we act, how we interact with one another. We are changed, whether we like it or not, and our language reflects that.

Isadora Kianovsky (she/her) is the Membership & Engagement Associate at Jewish Book Council. She graduated from Smith College in 2023 with a B.A. in Jewish Studies and a minor in History. Prior to working at JBC, she focused on Gender and Sexuality Studies through a Jewish lens with internships at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and the Jewish Women’s Archive. Isadora has also studied abroad a few times, traveling to Spain, Israel, Poland, and Lithuania to study Jewish history, literature, and a bit of Yiddish language.