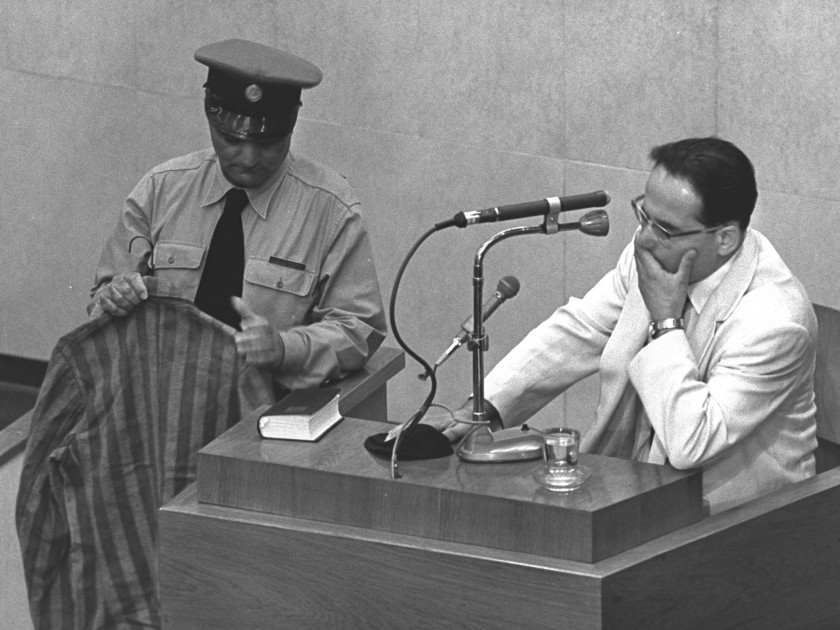

Witness Yehiel De-Nur Katzetnik (also known as K. Tzetnik) testifies during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, 1961.

USHMM, courtesy of Israel Government Press Office

Occupied Words: What the Holocaust Did to Yiddish by Hannah Pollin-Galay assesses the evolution and impact of Khurbn Yiddish — “Destruction Yiddish” — during and after World War II. In response to their experiences in the ghettos and concentration camps, Yiddish-speaking Jews began to use new or altered words and phrases to describe the world around them. These words could be phonically unpleasant, witty, morbid, rebellious, pointed; they encompassed complex reactions to a terrifying reality and its consequences.

Through her research, Pollin-Galay highlights the work of lexicographers and writers who used Khurbn Yiddish in their everyday lives. Each of these figures had different approaches to the study of these strange new words — they looked at the formation of Khurbn Yiddish, the various uses within the community of survivors, and its lasting influence on the Jewish experience.

I had the opportunity to speak with Hannah Pollin-Galay about her writing and research process, the world of Yiddish academia, and her next steps after finishing Occupied Words.

Isadora Kianovsky: I was lucky enough to hear you lecture about your research before reading this book, but I’d love to hear more about how you came to this work. What was your first introduction to Khurbn Yiddish (Holocaust Yiddish)? What drew you to this subject?

Hannah Pollin-Galay: I was listening to hours and hours of Holocaust testimonies in Yiddish as part of my dissertation work on language and oral testimony. I kept hearing words that I didn’t know, weren’t in the dictionary, and didn’t make sense. I also noticed that survivors sometimes shared these words with a special sense of mischief, with a kind of a wink and a nod. I sensed there was something going on with these words. Around that same time, by coincidence, my colleague Amos Goldberg showed me a copy of Nachman Blumental’s dictionary Verter un verterlekh fun der khurbn tkufe (Words and Phrases from the Holocaust Period). I was shocked to find that the quirky neologisms I had been hearing in oral testimonies were listed and explained in this book — that somebody else had heard them, gotten curious, and written it up. I dug a bit deeper and found that there were many more Khurbn Yiddish neologisms that I had imagined, and many other dictionaries like Blumental’s.

IK: What was your research process like for this book? Did you find any element particularly challenging or rewarding?

HPG: My project was driven by three main questions: What were the Khurbn Yiddish words invented? Why did these words matter so much to people (enough for some to dedicate years studying them and writing dictionaries)? And what kind of a legacy did they leave on Yiddish culture? These questions took nearly a decade to address and required me to try out a wide variety of research modes. There were unforgettably fun moments in the process: I sat in a hut off the grid in the Negev in order to read all of Chava Rosenfarb’s 2,000 page trilogy with as few interruptions as possible. I was invited into the kitchen of Sholem Eilati, the son of the lexicographer Israel Kaplan, to look through Kaplan’s diaries and dictionary. There were also months and months of very dry, empirical legwork — like sifting through all of the word search results for certain terms in order to find out if they could be considered Holocaust neologisms or not. Those word searches kept my project honest, so they were worth it in the end.

IK: Was there a Khurbn Yiddish word or phrase that you found especially fascinating to research? If so, what about it intrigued you?

HPG: I probably could have written an entire book about the word shabreven. The word would have struck most Yiddish speakers as funny-sounding gibberish before the war. It was invented (or re-invented) in the Warsaw ghetto to mean, “Taking ownerless property, also stealing.” There’s an obvious contradiction here: How can one word signify both a legitimate way of gaining property and an illegitimate way? All of the things that fascinate me about this word — its bizarre sound, its internal moral contradiction, its mysterious etymology — also fascinated people in the Warsaw ghetto. They debated this word robustly on every level, and in real time. I see the word shabreven as an archive of human desperation, of moral confusion, of a language gone wild — but also of curiosity, inventiveness, and self-reflection.

IK: Out of all the approaches examined in your book, is there one lexicographer or writer that you find yourself agreeing with more than others? Or, rather, if you cannot choose who you think is most “right,” does your own research take shape in a similar way to one of the figures’ that you discuss in the book?

HPG: I wanted the book to be a serious engagement with philosophies of language. I also wanted it to be historically grounded and personal. That was why I invested so much in telling the stories of three lexicographers and two writers — and their impassioned commitments to Khurbn Yiddish. I tried to let major philosophical debates speak through their lives and writings.

If I had to pick, I think that Nachman Blumental had the most expansive and coherent theory of Khurbn Yiddish. He saw word creation as a result of bodily and personal trauma, which then spiraled out into a collective word shift. He also addressed the widest range of questions, such as the encounter of Yiddish with other languages, the geographical spread of words, and the importance of metaphor.

At the same time, each of the other figures I discuss adds some powerful insight to the picture: Kaplan about humor, Spivak about the necessarily political nature of language choices, Rosenfarb about women’s experiences and also about the potential for community building in language, and K. Tzetnik about the importance of making language rebellious, purposefully interrupting polite discourse.

One person who read my manuscript said that I overidentified with the figures I researched. That’s probably accurate. I felt like each of them were my partners in trying to unlock this strange language. In each case, I got to some moment in their writings or their archives where I had to stop and take a deep breath.

IK: How much Khurbn Yiddish has become integrated into the modern day Yiddish lexicon? For instance, would a student like myself learn any of these phrases as part of a twenty-first century Yiddish language curriculum?

HPG: Almost none. Many leading Yiddish cultural figures after the war, like H. Leyvik and Yakov Zerubavel, were disgusted and embarrassed by Khurbn Yiddish. I think this disgust made its way into newspaper editorial policies, which then edited these words out of major standard-bearing publications. There are important exceptions: the creators of the Groyser verterbukh fun der yidisher shprakh (The Big Dictionary of the Yiddish Language), the ambitious multivolume Yiddish dictionary styled after the Oxford English Dictionary, did include Khurbn Yiddish words, with examples, often drawing from Blumental’s work. Unfortunately, that dictionary project ran out of funding after the letter aleph, so their message of Khurbn Yiddish integration didn’t really work.

By contrast, if you want to see Khurbn Yiddish, you can find it all over written or oral testimonies, where the survivor community didn’t edit this language out.

Language is always in motion. I think that the internet, social media especially, expedites changes in language.

IK: Your book describes many of the conversations and philosophies surrounding Khurbn Yiddish, especially post-World War II and with the creation of the State of Israel. Many Zionist institutions, writers, scholars, and opinions pushed against Khurbn Yiddish for various reasons, chief among them being the supposed ruminance on the grotesque, horrid, and tragic realities of the Holocaust. Some lexicographers, such as Israel Kaplan, used humor or sarcasm to counter this, to make Khurbn Yiddish more palatable for both its speakers and outside observers. My question is, through a lens of Khurbn Yiddish, do you think survivors are obligated to make their language — and the stories that that language represents — palatable to those who can never fully understand? Isn’t that the essence of Khurbn Yiddish — to translate the untranslatable?

HPG: Much of Khurbn Yiddish is unpalatable and embarrassing. Organizirn becomes a word for prisoners stealing from one another. Pipel is a young boy forced into sexual slavery. It’s not by chance that Benjamin Harshav, the only international scholar to ever mention Khurbn Yiddish in a major scholarly work, called it “grammatical subhuman stammer vis-à-vis the Master Race.”

But, other aspects of Khurbn Yiddish show wit, resistance, and ingenuity: Yiddish speakers, for instance, invented many faux acronyms to make fun of the Nazi German acronymic fetish. N.D.M. sounds like some Nazi organization, but it actually meant nit dayn mazel, as in “shit out of luck.” Just that term alone is a beautiful show of poetic autonomy. It’s an effort to reclaim the power to mean what you say.

I think that Khurbn Yiddishists — lexicographers and writers — wanted people to remember and bear witness to both of those aspects, the lowly and the witty, which often appear at the same time, and even in the same word.

As an additional outcome, Khurbn Yiddish also breaks down binaries about speakability versus unspeakability. The Holocaust did engender a major crisis in language. However, the result was not silence, but a transformation of language. Victims insisted on finding a way to speak.

IK: I found your chapter on Khurbn Yiddish in regards to female and effeminate bodies so interesting — especially considering that women’s bodies/femininity are still regarded in a similar negative manner by those in power today. Can you speak more about the remnants of this element of Holocaust Yiddish in modern day Jewish scholarship and language?

HPG: Sexualized female bodies are used to warn the Jewish people of moral downfall, or tell of a downfall that has already happened, in a number of sacred texts — from the Book of Lamentations to Ezekiel, and that’s only naming a few. What startled me about the Khurbn Yiddish words relating to this topic was how these age-old motifs came to life and informed the way that people thought and talked during the Holocaust. For me, the answer is not to turn away from the sacred texts that use women’s bodies as a symbol in this way, or to turn away from the Khurbn Yiddish texts that do so, but to widen the conversation and include creative responses to that tradition. I think that this is what Chava Rosenfarb does. She acknowledged and dramatized the Khurbn Yiddish motif of the sexualized woman, with its ancient precedents, but then turned it on its head — adding in female agency, humanity, individuality, and desire.

IK: I see many of the themes in Occupied Words present in our current world — what can we learn from Khurbn Yiddish to influence how we move through a still war-torn and ruptured society? How does it inform our efforts at cultural preservation — the physical, the historical, the social, the linguistic?

HPG: I’m sure that there are parallels in the current Israel-Hamas war, in Hebrew and in Arabic. I could list the Hebrew words that have changed or been added to everyday parlance following October 7th. I am curious to learn about how the war has impacted Arabic. I hope that people are researching or will do research on this.

IK: How has the transformation of language, both academic and colloquial, impacted the way we read and write today?

HPG: Language is always in motion. I think that the internet, social media especially, expedites changes in language. Looking through the lens of today’s American politics, the months July through August 2024 have changed the meaning of the extant terms like “weird,” “coconut tree,” and “cat-lady,” and brought in some new ones, like “AI’d” (which is one of many Trump neologisms). I think memes and twenty-four ‑hour global conversations online enable certain words to become marked, overstuffed with meaning or normalized at a break-neck speed. The COVID-19 pandemic also brought in a whole slew of neologisms, and transformed assumptions about what it means to communicate. Maybe some of these contemporary whirlwind experiences with words can give us a clue, in some minor way, into what it felt like for Yiddish speakers in the Holocaust.

IK: What are some other works you’d recommend to those interested in learning more about this subject?

HPG: Victor Klemperer’s memoir-cum-lexicon of Nazi German, LTI, is a must read. It gives the German version of the Khurbn Yiddish story.

IK: What do you hope a reader who is less familiar with this subject will get out of Occupied Words?

HPG: From what I see, this book speaks to two lay audiences. One is wordsmiths and armchair philologists: if you marvel at the cryptic acronyms and stump words you find in your — or, as in my case, your teenage offspring’s — TikTok account, just because secret codes are inherently fascinating, then this book is for you.

The second is people who are interested in the Holocaust, but need a new way in. There is sometimes an implicit message circulating in intellectual circles , that we already know what we need to know about the Holocaust, and so it is time to move on. This impatience or “off-trend” approach can lead to a dehumanization of Holocaust victims and survivors. Khurbn Yiddish words bring us close to Holocaust experience in a new way, showing less filtered aspects of what they lived through. These sources also demonstrate how much we still don’t know about the Holocaust, especially if something was recorded in Yiddish or it relates to women’s experiences. I think that Khurbn Yiddish can reawaken curiosity towards Holocaust victimhood and, as a result, reawaken empathy towards this episode of human torment.

IK: What does the future of your research look like? How would you say that your book, as well as Khurbn Yiddish as a concept, informs the current status of Jewish literature around the world?

HPG: So many great contemporary Jewish writers and filmmakers now incorporate historical research into their imaginative books and films. Who knows, maybe Michael Chabon will write his next novel with Khurbn Yiddish sprinkled all over it? Or maybe the Coen Brothers will have a ten-minute segment in Khurbn Yiddish? Just saying.

My next project is about nature, Yiddish, and the Holocaust. My aim is to unravel the knotty relationship between Jews, plants, and animals and how that informed their responses to catastrophe. I hope that this will also tell us something about cultural responses to the climate crisis we are currently facing.

Occupied Words: What the Holocaust Did to Yiddish by Hannah Pollin-Galay

Isadora Kianovsky (she/her) is the Membership & Engagement Associate at Jewish Book Council. She graduated from Smith College in 2023 with a B.A. in Jewish Studies and a minor in History. Prior to working at JBC, she focused on Gender and Sexuality Studies through a Jewish lens with internships at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and the Jewish Women’s Archive. Isadora has also studied abroad a few times, traveling to Spain, Israel, Poland, and Lithuania to study Jewish history, literature, and a bit of Yiddish language.