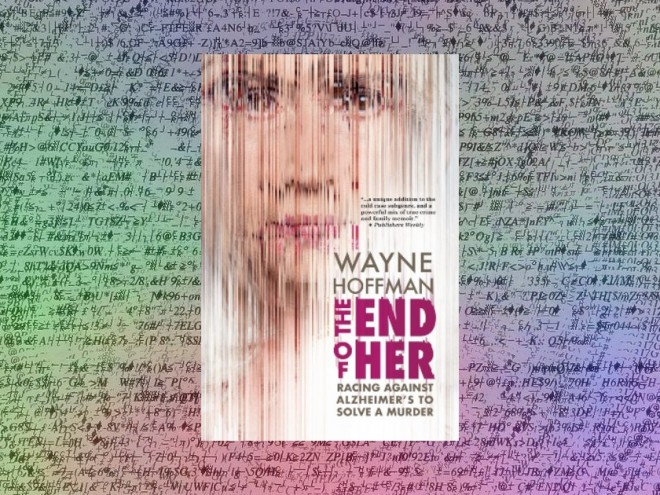

Part memoir and part mystery is how to best describe Wayne Hoffman’s new book, The End of Her: Racing Against Alzheimer’s to Solve a Murder. Utilizing his skills as both a journalist and a novelist, Hoffman recounts his quest to solve the murder of his great-grandmother, killed in her sleep in Winnipeg in 1913, and to share his findings with his mother before her mind is ravaged by Alzheimer’s Disease. In the process, the author’s search for truth explores issues of Jewish identity, the immigrant experience, familial obligation, love, and loss.

The author’s search begins after he tells the improbable story of his grandmother’s death to a room full of journalists. Skeptical himself, but encouraged by his colleagues, Hoffman begins to unpack the story by requesting his great-grandmother’s death certificate. When it arrives in the mail and reads “’bullet wound through the brain — homicidal,’” the author is hooked, and the quest begins.

As The End of Her continues, Hoffman weaves chapters about his mother’s decline and his family history into a single narrative. He includes family trees, photos, and newspaper clippings, both in English and Yiddish, to add to the reader’s interest and understanding. During his investigation, he unravels additional family mysteries and paints a vivid picture of life in Winnipeg’s thriving Jewish community in the periods before and after World War One and the influenza outbreak of 1918. He also explores the relationship between the immigrant communities of Winnipeg and the distrust, antisemitism, and biases that persisted among the groups that settled in Canada.

While The End of Her does not offer the satisfaction of a neatly resolved murder mystery, it does offer the reader a fascinating and well-written story that keeps one’s interest to the very last page. While unproven, the author’s final analysis of the unlikely events of 1913 is compelling. Equally compelling are Hoffman’s motivations for writing this story: to share his family’s rich and unexplored history, to honor his mother and capture her heartbreaking decline, and to understand himself a little better. He is successful in each of these goals and readers are enriched by it.

Jonathan Fass is the Senior Managing Director of RootOne at The Jewish Education Project of New York.

Discussion Questions

Courtesy of Wayne Hoffman

- The narrative that drives the book is sparked by a single photograph. Do you have a photograph that contains entire family stories for you — a picture that would be the beginning of your own book? In an age when we take pictures with our phones and post them publicly by the thousand, are photographs less precious than they used to be? Or is it the opposite: that now, we can create entire narratives from hundreds of photographs, rather than relying on one or two in a photo album on a bookshelf?

- The author travels across Western Canada to see where his great-grandparents lived. Have you ever traveled to the place where your parents — or grandparents, or great-grandparents — grew up? Had your parents told you stories about those places, and did going there change how you pictured them in your mind?

- Being named in a relative’s memory is a recurring theme in the book. Are you named in someone’s memory, or honor? Does it make you feel closer to that person? How much do you know about that person — and do you know more than you would if you hadn’t been named for them?

- The author relies on many sources of information while investigating the events of a century ago: official documents, newspaper reports, relatives’ personal memories. Which of these do you think is the most trustworthy or accurate? The least? Over the past century, have these sources of information gotten more or less trustworthy?

- In the book, the residents of Winnipeg’s North End primarily spoke other languages — Yiddish, Polish — while local police officers and journalists only spoke English. What difference do you think this made in the investigation, from the initial reporting to the inquest? How much do you think this is still an issue today for immigrant communities dealing with authorities, when it comes to reporting crime or seeking justice?

- What role do you think antisemitism played in the murder of Sarah Feinstein? Do you think it played a role in how the crime was handled — by police, journalists, jurors, or the general public? Would that be different today?

- If you knew about a similar event in your own family history — a crime, a tragic event, something that had been covered up — how would you go about finding out more information? If other relatives didn’t want to “dig up the past,” would you do it anyway?

- In the years after the murder, Sarah Feinstein’s family scatters; cousins don’t know each other at all, and even siblings rarely see each other. In an age of social media and instant, inexpensive communication, do you think families stay in closer contact than they did a century ago? What difference does that make for families sharing stories and information about the past?

- Is it important to you to keep in contact with your cousins? Second cousins? Third cousins? Do you make an effort to reach out find more distant relatives, and stay in touch? Why or why not?

- The author’s mother is suffering from dementia, which they later realize is Alzheimer’s disease. How would the story have been different if she’d been suffering from a disease that primarily had physical effects, rather than memory-related ones? What if she’d been perfectly healthy? Would the investigation into the past have happened at all?