When I started writing a novel inspired by a true-crime murder, I didn’t expect it to lead me to think about forgiveness. I began really with the opposite: a divorce that spiraled out of control, brutal family dysfunction, and a sinister murder-for-hire plot.

The news story first caught my attention because I had a very tangential connection to the person who was murdered. I was horrified as soon as I heard the news, and went down the rabbit hole of coverage springing up around it. Initially there was speculation that the murdered man — a law professor at Florida State — might have been killed by a student unhappy with a grade, or by a colleague who disagreed with his theories of constitutional law. Then, the articles would go on to note that he had been embroiled in a contentious divorce. As soon as I read that, I felt like I had arrived at the story’s beating heart.

For years after this murder, I followed the news as members of the ex-wife’s family were implicated and eventually arrested. I consumed everything I could: The regular coverage in Florida newspapers, and all the true-crime YouTube videos that cropped up. Eventually a Dateline special and a popular podcast were produced surrounding the murder. But I always came away from these dissatisfied; so much information about the forensic investigation and the eventual legal proceedings was readily available but I wanted the human story.

How could this seemingly ordinary family (allegedly) have done such a horrible thing? How could a divorce escalate so badly? No Dateline special could tell me what the family members thought about as they fell asleep the night before they committed this crime, or what they felt when they looked in the mirror the next day. What cold-blooded calculations, what terrible blind-spots, what haunting dreams, what eviscerating regrets clouded their thoughts? No matter how much I googled, I would never gain access to their inner lives, to their souls.

How could this seemingly ordinary family (allegedly) have done such a horrible thing?

The only way to come close to an answer was to use this real story as a springboard and imagine my way inside. I might not have been able to capture what really happened, but in a novel, I could go in search of larger truths about family love and loyalty, about blinding anger and dangerous escalation. In order to do so, I needed to write from the point of view of the family members who conspire to commit the murder; they might have been the least sympathetic but to understand the story required me to ask what pain did they suffer, what excuses did they construct? Most of all, I had to wrestle with why my characters couldn’t soften or forgive.

What made it so tragically impossible for them to turn back?

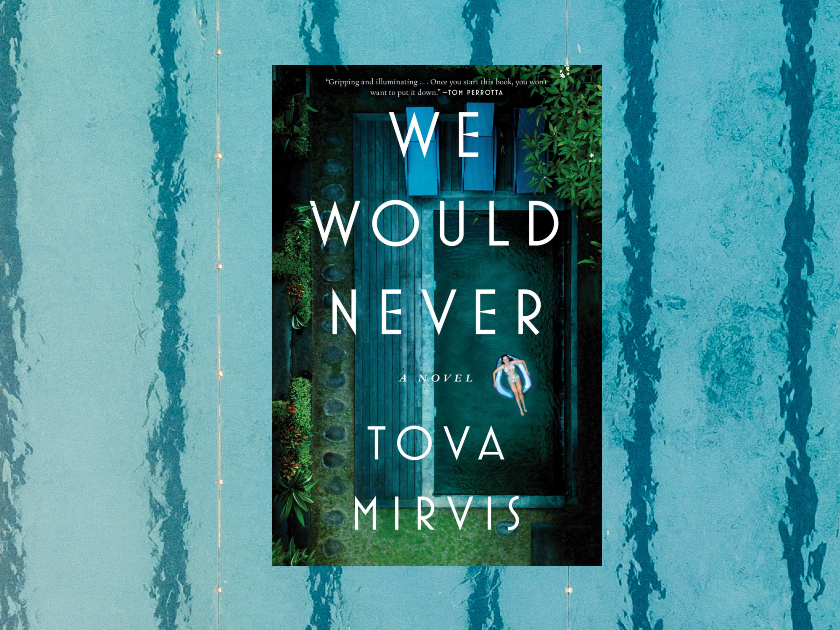

In some sense, I had to offer my characters a kind of forgiveness, even if they had been so incapable of doing that themselves. Though I knew what they were intending to do, at least at the start of the book, they hadn’t yet done it. I had to treat them as being in possession of a free will where they could still back down. And as much as I abhorred their potential actions, I had to see what made them sympathetic and human. “For the drama to deepen, we must see the loneliness of the monster and the cunning of the innocent,” the memoirist Vivian Gornick wrote in her book The Situation and The Story, and I thought about this every day as I wrote We Would Never. Could I excavate that loneliness? Could I flesh out that pain?

This kind of empathy lies at the heart of writing fiction. To write fiction is to let go of the need to judge and condemn. So much of my urge to write stems from the desire to understand what it’s like to be someone else — not the surface layer but the complexities beneath. Sometimes that urge arises from a frustration with the real world where all too often we are presented with scrubbed, curated facades. This doesn’t mean we will always like what we find, but to inhabit another point of view is not to excuse; to imagine is not to endorse. Nor is it a zero sum game — to be willing to gaze at the loneliness of the monster need not diminish our empathy for the victims. But it does put us at risk of seeing in the monster a sliver of humanity, and in doing so, the monster is no longer quite as distant from us. In order to create relatable characters, I had to let myself see parts of myself in them. What kind of anger might I be capable of? When have I hardened myself rather than been willing to forgive?

This kind of imaginative empathy lies at the heart of forgiveness more generally as well. Real forgiveness — not just perfunctorily accepting an apology — is often a long, multi-layered process, and there are of course things that cannot be so easily forgiven. But when we are really able to forgive, it requires that same willingness to look at the larger story, to imagine the experience of someone else, and even in the most painful of moments, be willing to see one another’s humanity.

We Would Never by Tova Mirvis

Join us for a conversation with Tova Mirvis and Dan Slater on March 31st at 7p.m. ET at The Jewish Museum! This Unpacking the Book event will delve into portrayals of crime and criminals in America. Through their works of fiction and nonfiction, we can trace how changing conversations about crime are a reflection of the broader world we live in today. Moderated by writer and podcast host, Stephanie Butnick.