Earlier this week, Tova Mirvis wrote about the value of personal writing. Today, she delves into the many memoirs she read before writing her own, The Book of Separation, out later this month from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. She has been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

Before I could write a memoir, I needed to read.

I was primarily a fiction writer and read mostly novels. But before writing The Book of Separation, I decided to spend a year reading only memoir. I asked friends and fellow writers for suggestions. I made lists and assembled a stack of books. I kept a notebook where I wrote about what I could learn from each memoir. How did the author structure the story? How did the author make use of flashbacks? How did the author create a compelling voice?

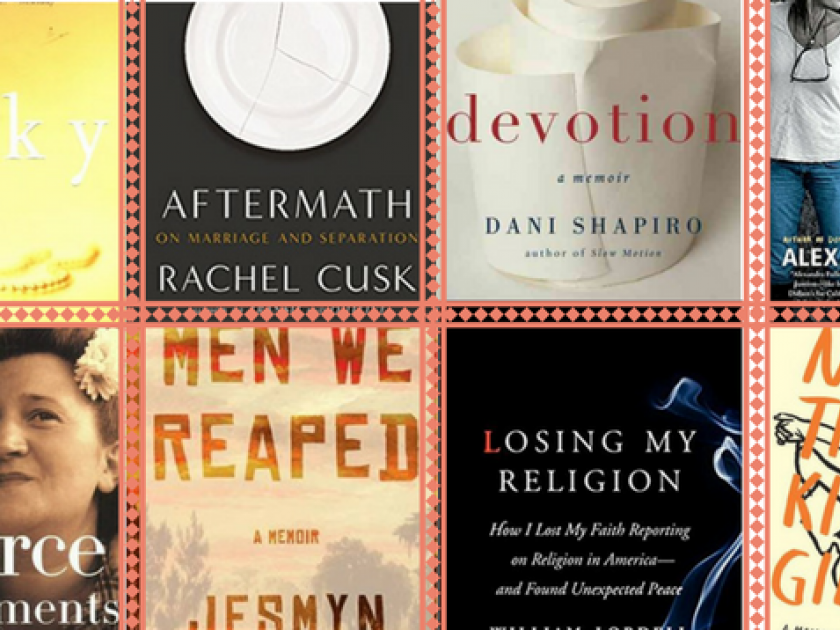

I began by re-reading two of my favorite memoirs: Devotion by Dani Shapiro and Aftermath, by Rachel Cusk. I loved Devotion for its probing questions and compassionate voice, Aftermath for its blunt force honesty. I had turned to these books for comfort as I navigated my divorce and leaving my Orthodox Jewish world, and my copies were well-worn, passages underlined, pages creased.

From there, I set out. Memoirs of childhood. Memoirs of addiction. Memoirs of divorce. Memoirs of coming of age. Memoirs of excursions and adventures. I scribbled notes in the margins, folded down the corners of pages I wanted to return to.

There were books whose stories haunted me – the voice of the writer pained, honest, bold. Reading them, I felt like I understood not just the author’s story but the world around me more deeply: Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped; Alice Sebold’s Lucky; Pang-Mei Natasha Chang’s Bound Feet and Western Dress; Caroline Knapp’s Drinking: A Love Story.

There were books that parceled out wisdom about how to forge a genuine self: Fierce Attachments by Vivian Gornick; Through the Door of Life, by Joy Ladin. My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff was a coming of age story so sure-handed and moving that I devoured it in one sitting. In Cabin, Lou Ureneck turned the process of building a cabin into a pensive, moving exploration of family and growth.

Some books, like Alexandra Fuller’s Leaving Before the Rains Come, I read more than once. This memoir, about Fuller’s divorce set against the backdrop of her African family and upbringing, was lush and piercing. On each page, I stopped to take in a moment of beauty. “In the end, at least in this end,” she wrote, “the world beyond me and the world inside me could no longer exist in the same place and I broke.”

I underlined and underlined.

I was particularly interested to read memoirs of leaving the ultra-Orthodox world, especially Shulem Deen’s searing, masterful All Who Go Do Not Return, and Leah Vincent’s bold, powerful Cut Me Loose. In both, the pain of forging a change and the bravery required to do so was apparent on every page.

These bore much in common with memoirs that explored leaving other religious worlds. Through the Narrow Gate and The Spiral Staircase by Karen Armstrong describe the author’s journey to becoming a nun and then the slow leaving of her convent. What captivated me was her portrayal of the mystery and power of religious faith even as she describes the slow encroachment of doubt. I also loved Losing my Religion by William Lobdell, a Catholic journalist who covered the Catholic sexual abuse cases and whose faith was burned away as a result.

I savored Not That Kind of Girl by Carlene Bauer, which traces her desire to be a good girl inside her Evangelical Christian world, and the process by which she came to question her role there. In this book, the author’s voice jumped off the page and carried me into a world that was both foreign and familiar. “As far as I could tell,” Bauer writes about the official church teachings, “that was the only story told by the officious soul, and the real and true sadness had been excised for a more mellifluous account.…”

I folded over this page. My Orthodox Jewish upbringing in Memphis was a world far from hers, yet I knew the feeling that parts of your experience were not permitted. The particulars might have varied, but the emotional truths landed close to home.

In all these memoirs, I found a common theme: the transformation of the self over time. In many of these memoirs, the author leaves one world and begins to make way for another. The kinds of leavings varied – leaving a religious world, a childhood, a destructive way of being, a former self. But in all, there was a palpable sense of the loneliness that comes with change and departure.

This was a feeling I knew well. In the years of leaving my marriage and religious community, I felt more than anything the sense of the known world receding – the way it looks when you set sail from a fixed shoreline and move into something that is uncertain and unmapped. Throughout those years, I wondered: did anyone around me feel this way too?

The answer, for me, came in these memoirs.

Reading memoir helped teach me how to write memoir. But most of all, my year of reading helped me feel a little less alone in the world. Now, when I look at these books on my shelves, I think of the authors as fellow travelers. These memoirs are books to take with you on the journey across.