Image from Esquire Classic:“Helen Gurley Brown Only Wants to Help” by Nora Ephron, February 1, 1970

In the February 1970 issue of Esquire, an article by Nora Ephron appears in which she writes about the iconic Helen Gurley Brown. Ephron encapsulates Gurley Brown’s controversial reign as editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan magazine as only she could, especially considering that Ephron wrote for the publication and worked intimately with Gurley Brown. Some would even go so far as to say that Gurley Brown discovered Nora Ephron.

The year was 1965, early in Gurley Brown’s tenure as Cosmopolitan editor-in-chief. Hearst executives were already nervous about her stepping into the role. After all, she had no previous editorial or magazine experience. Hearst had been publishing magazines since the 1800s but in the early 60s, subscriptions began to steadily tank. Assuming that Gurley Brown’s attempt to resurrect the magazine would flop, Hearst handed her an impossibly tight budget from which to produce.

The brazen editor went scouting for new talent, talent that she could afford. That’s when she plucked Nora Ephron from near-obscurity. At the time, Ephron was a reporter for the New York Post and was, of course, was already very familiar with Gurley Brown. Two years before the women met, Gurley Brown had published the scandalous bestseller Sex and the Single Girl.

The brazen editor went scouting for new talent, talent that she could afford. That’s when she plucked Nora Ephron from near-obscurity.

Ephron was already engaged to her first husband, Dan Greenburg, so why would a nice Jewish girl, with a nice Jewish guy, want to read the shocking escapades of single women who celebrated sex — casual sex, monogamous sex, naughty sex, and even forbidden sex with married men? But read it she did, and probably — like millions of other women — read it more than once. In Sex and the Single Girl, Gurley Brown wrote about her encounters with older men, younger men, handsome men, not so handsome men. She didn’t discriminate even when her lovers did, as in the case of the antisemitic man she dated who openly condemned her Jewish friends, refusing to socialize or even meet them. But he was great in bed and, in Gurley Brown’s world, which was enough to erase a multitude of sins. One has to wonder how Ephron, a proud, though not observant Jewish woman, felt about all that when the two finally came face to face.

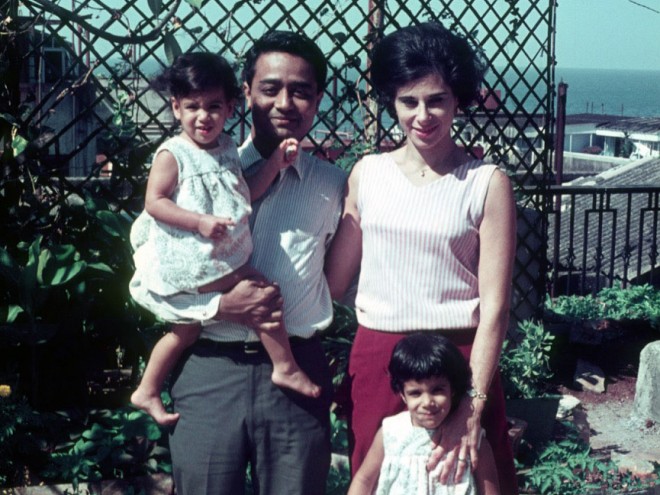

I like to imagine that first encounter: There was Ephron, big toothed, with thick, unruly dark hair — which Gurley Brown must have envied as she always wore wigs to hide her thinning hair. Gurley Brown must have recognized aspects of herself in Ephron who, like Gurley Brown, was smart, irreverent, and not afraid to write what few women would dare talk about. The two women would come to realize that they had much in common. Ephron grew up in Beverly Hills and Gurley Brown in Los Angeles; Ephron’s parents were both screenwriters and Gurley Brown’s husband, David Brown, was an acclaimed Hollywood producer. It was almost as if the two had been circling one another for years and their lives were destined to intersect. I think they must have formed an immediate bond because they weren’t classic beauties, had learned to thrive with their heads, not their looks. And of course, they both had chutzpah.

Gurley Brown gave Ephron a shot at writing her first magazine piece, asking her to do an article on the chorus line at the then-popular Copacabana nightclub. Though Ephron was thrilled at last to get a magazine assignment, by all accounts, she wasn’t all that enamored of the club or the chorus line. But the article gave her a foot in the door and that was the beginning of many articles she would go on to write for Cosmo.

By now Ephron was married and though she wrote for the magazine, she didn’t necessarily want her fellow New Yorkers knowing she was a Cosmo reader. She would commute about town, keeping the cover hidden. Like millions of women, single and married, it was her guilty pleasure.

Setting Ephron, the Cosmo reader, aside, I wonder how Ephron, the Cosmo writer, felt about having her work edited by Gurley Brown. The editor-in-chief was always pushing her writers to dig deeper and commit to paper the very things that her girls (which was how she referred to her readers), dared to think about late at night, all alone, with the lights turned out. Gurley Brown demanded this type of candor from her writers and it shaped some of Ephron’s most notable pieces including, “Men, Men Everywhere But…” whereby Ephron spelled out what it was like to be a gawky, self-conscious single girl amidst a sea of potential male partners. She was also brave enough to volunteer to be the subject of a Cosmo Beauty Makeover. Ephron even poked fun at New York’s upper crust in a piece called “Women Wear Daily Unclothed.” The revered fashion bible was not amused and turned around and sued Cosmopolitan.

The editor-in-chief was always pushing her writers to dig deeper and commit to paper the very things that her girls (which was how she referred to her readers), dared to think about late at night, all alone, with the lights turned out.

From my research, I know that Gurley Brown was a meticulous, hands-on editor. She was famous for shredding Liz Smith’s copy, firing Rex Reed for writing what she called pippy-poo copy and slashing all polysyllabic words with her red pen. I can’t help but think that Gurley Brown did much to shape Ephron’s future writing including Wallflower at the Orgy and I Feel Bad About my Neck. Like Gurley Brown, Ephron was able to strike a balance of irreverence and vulnerability.

Fast forward to 1970. Ephron had already made a name for herself when she sat down with her former boss for the Esquire interview. According to Gerri Hirshey’s biography on Gurley Brown, Not Pretty Enough, the editor-in-chief was ready to come clean, squeaky clean about everything! She even gave Ephron the name and contact information for one of her early conquests. Ephron, exercising better judgment than Gurley Brown, opted to spare the man and his wife from exposure in the article.

Something else struck me as I was working on my book: When one thinks about the classic Cosmo Girl, Nora Ephron is probably about the last person that comes to mind. But in fact, Ephron was exactly who Gurley Brown was thinking of when she took over as the editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan. Gurley Brown, who often referred to herself as a mouseburger, wanted nothing more than to help girls everywhere become their very best selves. That was the spirit behind Ephron’s Esquire piece, and I’d like to think that some of that rubbed off in Park Avenue Summer.

Renée Rosen is the bestselling author of Park Avenue Summer, White Collar Girl, What the Lady Wants, Dollface, and the young adult novel Every Crooked Pot. She lives in Chicago.