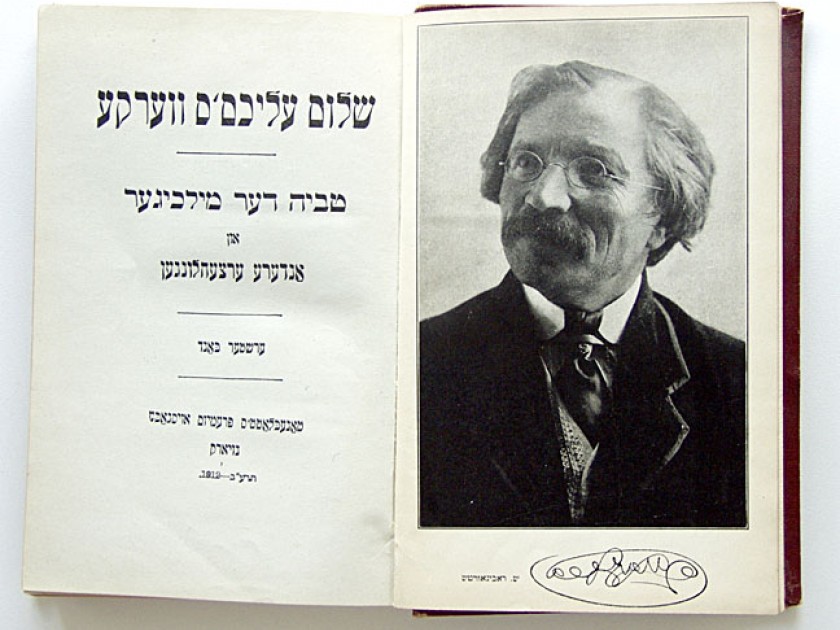

Curious about Tevye’s lesser known daughters, the four left out of the theatrical adaptation of Fiddler on the Roof, I picked up an old volume of Sholem Aleichem’s The Railroad Stories. The rich, humorous language of this Yiddish storyteller (in translation), evoked the familiar warm feeling for Tevye who, while recounting his troubles, comes across also as a lay philosopher.

Then I stumbled upon another short story in the collection, “The Man From Buenos Aires.” This time, the shady, sleek character who brags about his business success in Buenos Aires, but never reveals the nature of his enterprise, left me feeling queasy — just as the author had intended.

I understood what business brought this fellow his riches. Sex trafficking.

By association, my mind returned to a day in 1995, at the International Women’s Conference in Beijing, when an elderly Filipina told the audience about her past suffering as a “Comfort Woman.” She had been one of many thousands of girls captured by the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII and forced to serve the sexual needs of its army.

The tiny woman with bowed legs had an operatic voice. The interpreter spoke her words through the headphone, but what I heard was the Filipina’s cry in a lyrical, high-pitched voice that, without the aid of a microphone, reverberated in the hall as the woman recounted the indignities, torture, and injustices she had suffered. Her exquisite voice imprinted in my head the tragic story of all subjugated women.

Her exquisite voice imprinted in my head the tragic story of all subjugated women.

Reading Shalom Aleichem’s story now reignited those synapses in my brain. I had been faintly aware of a blot in the past of Jewish immigration to Argentina, some of whose members had engaged in pimping and prostitution. I recalled that in 2007, on my third trip to Buenos Aires, I had visited the new Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA,) the imposing building that housed all Jewish organizations, (after the previous one had been bombed in 1994, killing eighty-five people and injuring hundreds of others). I ambled into the library, where I chatted in English with the librarian. However, when I asked her casually about “the Jewish prostitutes and pimps,” she suddenly forgot her English.

Talia in 1996 in Buenos Aires, demanding the government’s investigation into the 1994 AMIA bombing.

Indeed, the idea of Jews involved in such activities was so foreign to our own perception of peoplehood that even Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founder and its first Prime Minister, had once said, “We will fulfill our dream of being a normal people when we have our own thieves and our own prostitutes.”

I put aside Shalom Aleichem’s thought-provoking 1909 story and turned to modern-day Google. Within minutes, I was printing out mountains of documents about Zwi Migdal, the legal union of Jewish pimps headquartered in Buenos Aires that had operated with impunity for seventy years. All I could think about was the girls and women caught in the nets of lies and false promises of marriages and jobs, lured from the shtetls to “the golden America.”

It had always been clear to me why Fiddler On The Roof avoided showing on stage the truly brutal horrors of the hundreds of pogroms: men’s beards torn off with the skin, pregnant women’s bellies slashed open, children’s heads bashed against walls. The lure of America, given these ongoing vicious persecutions in Europe, was clear.

I took my pile of printouts to a beach in Boca Raton, FL, where I enjoyed a warm winter and a cool drink, but as I read the articles, my skin prickled with dread. Suddenly, against the roar of the ocean rose the haunting voice of the tiny Filipina, crying to be heard, to be remembered, not to be judged and stigmatized by what had happened to her. Upon returning to her village, she had been shunned. Sullied, she could never marry, which in her society was the only way for a woman to be fed and housed. Unlike many of her fellow sex prisoners, she did not commit suicide then, or later. Instead, her spirit carried her to old age while she continued to seek an apology from the Japanese government, who steadfastly refused to admit this war crime.

In my head, the woman’s cries became the wails of the Jewish women victims I was now reading about. Once broken by unimaginable torture throughout the weeks-long ocean-crossing, they were forced into prostitution. At its height, Zwi Migdal employed 30,000 Jewish women across South America (even reaching New York’s Lower East Side), netting $50,000,000 profit a year.

It wasn’t hard to imagine what I would have chosen had I lived in a shtetl during those awful times and a well-heeled stranger showed up with the promise of a wonderful life in America. Wouldn’t the optimistic Tevye, too, send one of his daughters had they met that conniving man from Buenos Aires?

Wouldn’t the optimistic Tevye, too, send one of his daughters had they met that conniving man from Buenos Aires?

Her misfortune would have doubled when she found herself shunned by her own people. The upstanding Jews of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay turned their backs on the teenage Jewish victims, and the benevolent societies, on which we Jews pride ourselves, shut their doors in the faces of the prostitutes and their children. The upstanding Jews refused to bury the sullied women in their cemeteries, as though the dead, too, could be contaminated by their impure lives.

Having lived at the edge of society, never viewed as victims, these girls and women were purposely forgotten, as later manifested by the silence of the librarian.

But that was not how I, with my twenty-first century’s sensitivities, viewed them. In finding the human spirit beneath their painted faces, indecent clothes and crude solicitations, I wanted to honor their suffering and swallow the redemptive cure of truth-telling.

It took enormous courage to plunge into this complex tale. I had always avoided writing or commenting publicly about anything bad relating to Jews; we have plenty of enemies to do that. It took further courage to take the emotional journey into the dark world of the sexual slavery of — according to my research — between 150,000 to 220,000 Jewish women victims of Zwi Migdal. But Sholem Aleichem’s story, forever lumped together with Tevye’s stories, gave me permission, and the haunting pitch of the Filipina that turned into a Jewish keening chorus compelled me to forge on. I crawled under the skin of Tevye’s daughter in order to bring compassion where none had existed before for these poor souls.

Talia with women of different parts of the world taken at her UN presentation in March 2007 about infanticide in China.

In the years it took me to feverishly pen the novel, a greater mission emerged: we, Jews, cannot change the past, but we can learn a lesson from it. By way of Tikkun Olam, we can honor these girls’ and women’s suffering by helping today’s victims who, 120 years later, are still lured by the same methods into the same tragic fates.

We must find the courage, or the voices of today’s victims will be silenced too.

Novelist Talia Carner has authored six historical and psychological suspense novels that shed light on social indignities and unexplored historical events. Both The Boy With The Star Tattoo and The Third Daughter were named Finalists by the Jewish Book Council in the Book Club Categories. Formerly the publisher of Savvy Woman magazine and a lecturer at international women’s economic forums, Carner turned from trailblazing projects centered on women’s issues to fighting for Israel’s image. Born in Israel, she lives in New York and Florida.