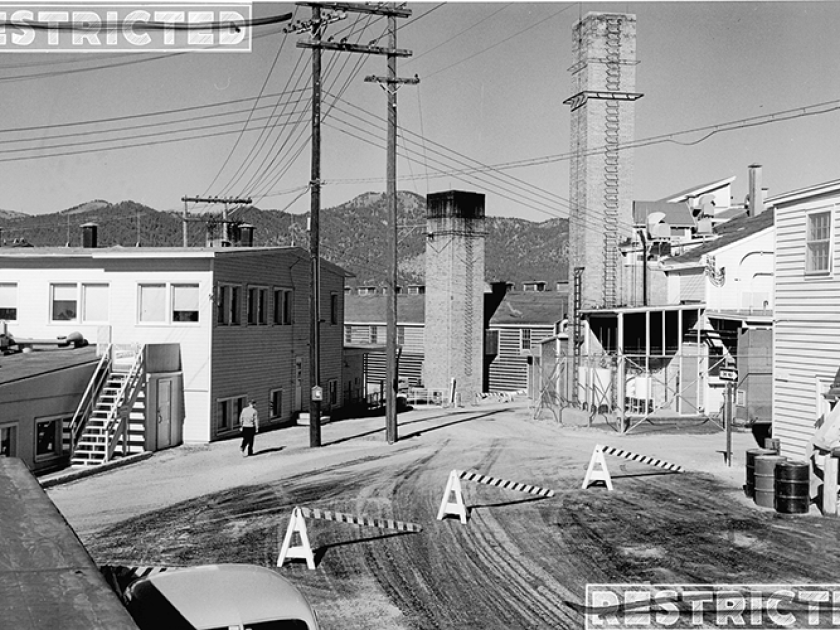

Los Alamos National Lab D Bldg, Boiler House, M and V buildings. United States Department of Energy, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Navigating Jewish identity today can feel like solving a riddle: what is three thousand years old, thrives on tradition, is complicated by political allegiance, and exists on a spectrum between theological and secular?

My novel, The Sound of a Thousand Stars, was inspired by my Jewish grandparents’ legacy. The story predates the founding of Israel, its history of conflict, and the current war. Traveling back in time may not solve today’s polarization, but it can demystify how we arrived here.

It all began in the summer of 1944, when at only twenty-six, my grandfather, Leon Fisher, signed on to contribute to top-secret research that, unbeknownst to him then, would help to build the atomic bomb. As a result of his necessary isolation during his time at Los Alamos, he lost all communication with his Orthodox Jewish family.

A young PhD just at the onset of his career, Leon was recruited not long after graduating UC Berkeley, where he’d enrolled in a class taught by J. Robert Oppenheimer. There, Oppie, as Leon knew him, had gained a reputation for lecturing with his head in the clouds, mumbling in Sanskrit, and forming risky associations. Like many liberal-leaning secular Jews, Oppie was attracted to communist ideologies, and these attachments would ultimately result in his security clearance being revoked in 1954.

To Leon, whose Orthodox family had emigrated from Romania to escape persecution, Oppie defied what it meant to be Jewish. Despite the quotas on faculty positions for Jews, he held a prestigious assistant professorship and established the country’s predominant school of thought on theoretical physics. Oppie didn’t keep kosher. He dined at opulent steakhouses, often treating his graduate students to meals Leon could never have afforded, surrounded by shimmering cutlery. As others have noted in Oppie’s biographies, he strutted around campus with such energy that his feet barely hit the ground. The laws of physics themselves seemed unable to touch him.

But in the decades of my life, in our living room, she was as tightlipped as my grandfather. We knew better than to ask, chewing silently at the dinner table.

In Los Alamos, Leon, the man I knew simply as Zaide, worked on the plutonium trigger of the Fat Man bomb, setting off dynamite behind blast walls and studying sparks and ignition. I only know this now, after sifting through the contents of my grandparents’ safe-deposit box and seeking out their still-living friends before they, too, passed away. My grandparents made the decision never to speak of their time at Los Alamos, even to us, their own family. I have spent years unearthing the meticulously scrubbed details of their lives, specifically the thirty-six months encompassing 1944, 1945, and 1946.

I pored over my grandmother Phyllis’s letters from Los Alamos. In them, she recounts having blindly followed Leon up the winding switchbacks to the isolated, top-secret mesa. Despite the tension it put on their marriage, my grandfather never shared what he was working on with her. Stoically, he reported to work inside a barbed wire – enclosed area, entering a top-secret steel laboratory known only as “Project Y.” Phyllis, whose life was consumed by the red, rocky mesa, swallowed her questions.

That all changed one afternoon when she pieced together what Leon was building. When she was pregnant with her second child, the two were debating baby names. Jokingly, Phyllis suggested “Atomic.” My grandfather stormed out of the room. Apparently, “Atomic Fisher” had been too close to “Atomic Fission.” But even after they confronted the truth of his work, secrecy forbade further discussion. Phyllis went on to deliver a jaundiced and colicky baby. She blamed her depression — a conviction she recorded in diary entries, where she cited her guilt over their contributions to the weapon that changed the world: “The specter of the mushroom cloud would follow us wherever we went.”

In 1985, Phyllis published a book of her letters that was translated into Japanese. But in the decades of my life, in our living room, she was as tightlipped as my grandfather. We knew better than to ask, chewing silently at the dinner table.

Since they’ve passed away, I’ve managed to scrape together a foggy vision of the community in which they resided on the mesa — a conglomerate of Jewish nonbelievers who still went through the motions of celebrating High Holy Days behind barbed wire because tradition is tradition. With six-day workweeks eliminating the possibility of observation of the Sabbath, my grandparents attended ad hoc services at Fuller Lodge. Phyllis wrote humorously about the flavorless matzo shipped up the hill in flatbeds, and her attempt to direct the non-Jewish volunteers who misinterpreted the matzo ball soup recipe, forgoing chicken broth and instead floating matzo balls in warm tap water.

For the members of Jewish Services Committee, who worked so diligently to find workarounds to smuggle prayer books and rabbis into the secret city, it must have felt surreal to gather around the common-room radio and debate conspiracy theories about Hitler’s missing remains — finding out by turns that he had perhaps ingested cyanide and died by suicide, or been killed by an exploding shell in his Berlin chancellery, or was fleeing by U‑Boat to Japan. Likewise, it must have hit differently for Leon in the days and weeks that followed. With Hitler dead and gone, he must’ve wondered who their new target might be.

“The specter of the mushroom cloud would follow us wherever we went.”

My grandfather was simultaneously proud of and wounded by his Jewish heritage. Phyllis had never been Jewish “enough” for his family. At their wedding, Leon’s parents had gaped at the plated creamed chicken, unable to consume the mixture of milk and meat. A San Francisco De Young, Phyllis was so Americanized she celebrated Christmas. But my zaide knew that across the Atlantic, no such distinction would be made for her. At the height of the war, the rumors of Jews being turned into soap and lampshades certainly influenced his choices.

As a child, I remember being confused by the multifarious nature of Jewish identity. I watched my mother, who never ate a bite of pork in her life, hide cans of clam chowder any time my paternal grandmother came to visit. Someone could be too Jewish and not Jewish enough at the same time. So, what might it mean to be Jewish in America today?

Beside me, my three-year-old rolls matzo balls between sticky fingers as we prepare to drop them in boiling water. I haven’t solved this riddle and likely never will. But what could be more Jewish than asking questions?

Rachel Robbins received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is a tenured assistant professor at Malcolm X College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago. A visual artist and two-time Pushcart Prize – nominated writer, her paintings have materialized on public transit, children’s daycare centers, and Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. She lives in Chicago with her husband, children, and Portuguese Water Dog. The Sound of a Thousand Stars is loosely based on her grandparents, who worked at Los Alamos but never spoke of their time there.