Author photo by Jordan Engle

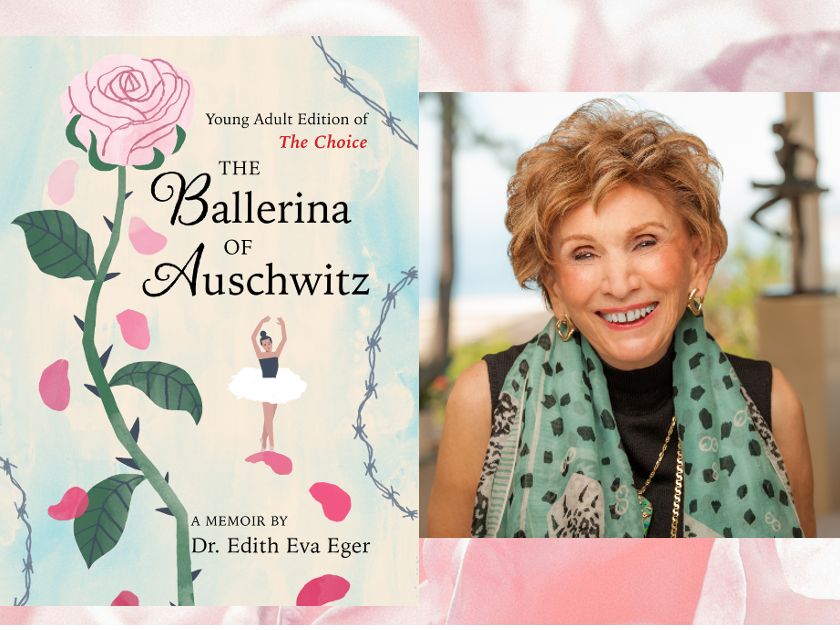

In 2017, Dr. Edith Eva Eger’s monumental memoir The Choice came out, detailing her survival in Auschwitz and her life after the war as a renowned psychologist. The Ballerina of Auschwitz is the young adult edition of Dr. Eger’s memoir, and the author describes it as “the book I wish I could have read when I was sixteen.” JBC’s Michal Hoschander Malen spoke with Dr. Eger about writing this book and revisiting this time in her life, her work as a psychologist, and her outlook on life.

Michal Hoschander Malen: How have you maintained a positive attitude in the wake of your experiences in Auschwitz? What gave you the strength to move forward?

Edith Eva Eger: I once worked with a beautiful couple whose child had died. Both parents were deep in grief, struggling to stay connected — with each other, with their living children, with life itself — in the wake of such a devastating and unexpected loss. It was as though their child died … and they died, too.

I faced a similar reckoning after the war. In healing from the horrors I experienced I also had to grieve what didn’t happen: my parents would never see me graduate from college or become a mother; they would never meet my future husband or dance at my wedding; they would never celebrate holidays with my children or grandchildren. Sometimes the feeling of loss was so absolute and excruciating that I didn’t want to keep living.

Yet I realized that if I gave up on life, it wouldn’t do my parents any good. It wouldn’t bring them back. The best way to honor them and ensure they didn’t die in vain was to make my life stand for something. To find meaning and purpose — and joy — in being alive.

This happened first in small ways: tasting cheese and salami and fresh-baked bread; hearing my sisters play music; feeling my own body relearn how to dance.

In beginning to savor tiny, everyday pleasures, I became more open to life itself. I became curious. I stopped asking, “Why me?” and began to wonder, What will happen next? I fell in love again. After all that death, I resumed the rhythm of life.

I tell my patients, “Pay attention to what you’re paying attention to.” Think about your thinking. If you think about fear, you’re going to have more fear. If you think about all the ways you’ve been let down, you’re going to experience more disappointment.

While there’s no healing in minimizing our pain, we always get to choose whether to focus on what we’ve lost, or on what we have. The violence of the Holocaust was senseless. And I survived. And I choose to embrace the gift of life.

MHM: The Ballerina of Auschwitz is the young adult adaptation of The Choice. Did you have a different perspective when approaching the material and writing for this audience?

EEE: Ballerina is the book I wish I could have read when I was sixteen.

I wrote this memoir from the point of view of my teenage self, yet there’s also a sense in which I wrote this book to the younger me. To the girl who was falling in love for the first time and seeking to find her place in her family and the larger world. To the girl whose life was interrupted. Who stood in the bitter cold, waiting her turn in the selection line, and wondered, “Does anyone know I’m here?”

To that young girl, that long-ago me, I say, “You made it! You’re free!” And to the youth of today, facing hardships and challenges of their own, I say, “If I can do it, so can you.”

Writing Ballerina helped me see that my story of atrocity is also a love story. As I experienced the worst of humanity, our capacity for unspeakable darkness and cruelty, I also experienced our capacity for hope and connection. My story begins and ends with love — familial love, romantic love, self-love.

MHM: What do you hope young people will gain from reading The Ballerina of Auschwitz?

EEE: I hope young people will harness the freedom of choice in their lives. And I hope they will embrace their brilliant, one-of-a-kind uniqueness.

I used to think that being strong meant getting as far away as possible from my painful past. I tried for decades to outrun it, suppress it, deny it. But in becoming a psychologist and helping others heal, I realized that if I was running from my own past, I was still a prisoner.

Young adults know all too well that there’s so much in their lives they can’t control. We can’t choose what happens to us, but we can always choose how we respond. There’s nothing more empowering than choices. I want my young readers to know that the more choices they have, the less they will be a victim of anyone or anything.

In this capacity to choose we find our freedom — and our authenticity. I want my young readers to know: There will never be another you.

We can’t choose what happens to us, but we can always choose how we respond. There’s nothing more empowering than choices.

MHM: Could you speak about the experience of revisiting your incredibly powerful and influential memoir to create The Ballerina of Auschwitz?

EEE: Here’s something I didn’t expect when I started writing my first book: It was harder for me to write The Choice than to survive Auschwitz. In Auschwitz, all I had to do was get from one moment to the next. To write, I had to feel all the feelings.

As I worked on Ballerina, I had to feel it all again. I wrote in present tense — this is what I ask my patients to do when they tell me about a traumatic or painful experience, to tell it as though it is happening now. When we remember in this way, we aren’t in our heads, intellectualizing, talking about the past. We’re reliving it in a visceral, immediate, embodied way.

We can’t heal what we don’t feel. While The Choice incorporates my life as a psychologist, and allowed me to reflect on trauma and healing through a professional as well as personal lens, Ballerina has been therapeutic in a different way, bringing me even closer to the years just before, during, and after the Holocaust.

I also wrote Ballerina with a greater sense of my own mortality. When my sister Magda, with whom I survived Auschwitz, died (at age 100!), I realized that if there was anything else I wanted to share with my beloved readers, the time was now. It felt right for me — the great-grandmother, and renowned psychologist — to give the floor to young Edie, to say to that girl brimming with life and possibility, “Tell me more.”

MHM: You have said that you think it is important for people to visit Auschwitz. Why do you feel this is important? Do you think today’s rising atmosphere of antisemitism changes the perspective of visitors to the site?

EEE: Antisemitism wasn’t a Nazi invention. Prejudice against Jews existed long before Hitler, and it didn’t vanish with the perpetrators of genocide. Anyone can be taught to hate. In this age of social media influence and disinformation campaigns, we are particularly vulnerable to rhetoric that exploits our fears and grievances, and magnifies our perceptions of difference and division. We have to take active steps to broaden our perspective, to see things from multiple points of view.

We also need to be proactive about disrupting stale patterns of thinking and behavior. We tend to repeat patterns in our lives, even when the patterns may be self-destructive. (This is why I ask my patients, “Are you evolving or revolving?”) If we are going to disrupt self-defeating patterns, the first step is to recognize them. This is true in individual therapeutic work — and it’s true for communities and societies. We say,“Never again,” but these words are meaningless without action. If we don’t want to repeat the mistakes of the past, we have to summon the courage to face what happened and to choose differently.

One of the most chilling things I realized after the war is that had I been born German and gentile, I would have made an ardent Hitler Youth. I was so hungry to belong, so idealistic. All that human yearning could easily have been manipulated and harnessed in support of hate.

Visiting Auschwitz forces us into an uncomfortable yet vital recognition: that could have been me. I could have been a prisoner — or a captor.

We’re taught to hate. We’re born to love. It’s up to each of us to reject hate and reach for our birthright: love.

MHM: How do you use your experiences and your life story to help others process trauma? What makes it possible for survivors to “move on” and lead a productive life?

EEE: I learned this the hard way: There’s no freedom in minimizing what happened, or in trying to forget.

In a sense, we never “move on” from trauma. The horror I experienced eighty years ago is still with me. I have nightmares and flashbacks. There are days when I feel angry, when I miss my parents beyond words, when I struggle to remember that I’m safe. Yet in the ongoing work of coming to terms with what happened, I’ve discovered that Auschwitz was my greatest classroom. I found inner resources I never knew I had. One of the fundamental principles I use in my therapeutic work is that our worst experiences can also be our best teachers.

In my own healing journey I discovered that the prison the Nazis put me in was much easier to escape than the mental prison I constructed for myself after the war. In my second book, The Gift, I examine the prisons we make in our minds, and how to free ourselves from the self-limiting beliefs and behaviors that keep us captive.

Time doesn’t heal; it’s what you do with the time. Ultimately, all therapy is grief work. It’s in giving up the need for a different past so that we can embrace the gift of life: all that we have, and all that is possible.

MHM: What are some of the books you have read that have influenced and shaped your outlook on life? Are there any books you read as a young adult that have stuck with you over the years? Or, are there any books you think young adults should read?

EEE: The book that literally changed my life, giving me the courage and permission to talk about my past and illuminating freedom of choice as my most essential personal and therapeutic framework, is Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. It’s brilliant and exquisite — a must-read. I also highly recommend Erich Fromm’s Escape from Freedom and The Art of Loving, and Martin Buber’s I and Thou.

As a teenager, I was a voracious reader. I loved philosophy and psychology — my high school book club read Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams—and I appreciated books, even fiction, that brought history to life. It’s so essential to be able to imagine our way into others’ experiences. This is how we learn empathy and compassion, and defeat black-and-white thinking.

Reading also taught me how to be comfortable in an inner world, a place that became my refuge in Auschwitz, a place I still visit for nourishment and inspiration.

To be a writer myself, and to help my readers cultivate their own inner worlds and resources, is a dream come true and a gift beyond compare.

The Ballerina of Auschwitz: Young Adult Edition of The Choice by Dr. Edith Eva Eger

Michal Hoschander Malen is the editor of Jewish Book Council’s young adult and children’s book reviews. A former librarian, she has lectured on topics relating to literacy, run book clubs, and loves to read aloud to her grandchildren.