Miss-Art, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When I shelved my law career to become a writer, the most common advice I was given was “Write what you know.” I’ve always preferred “Write what you want to know.” Write about the things that horrify or fascinate you. Write about the things that anger you, or that you struggle to understand.

I write to make sense of the things that scare me: war, intolerance, violence, and hate. My father was a Holocaust survivor, so it makes sense that all my novels feature a teenager fighting to live a life of their own choosing. It makes sense that what fuels my writing is fear.

I only came to learn my father’s Holocaust story when I was in my thirties and he’d been diagnosed with ALS. My father had disconnected from the past as a way of moving forward. He’d kept his story — and his camp number, which he’d covered with a tattoo of a flower — hidden from us, because in Australia, he didn’t feel like a number anymore; he wasn’t a victim. And maybe he never mentioned the camps because he didn’t want that chapter of his life to be our personal inheritance. Maybe, instead of passing on his trauma, he wanted to gift us resilience, hopefulness, compassion, and pride.

But now he was dying, and it was time for him to tell us his story. Time for us to learn what he’d seen, and how he’s survived it. The telling took nine nights, over twenty-five hours. There was no question he wouldn’t answer and, three years later, when he could no longer speak and was forced to type his thoughts on a keyboard that spoke for him, he continued to answer my questions — questions that changed our relationship.

Revenge is nice, but change is better. And who better to target than teenagers, who are still working out who they are and what sort of world they want to live in?

Just before he died, I promised I’d tell the world what had been done to him. I kept that promise when The Tattooed Flower was published in 2006, but something continued to draw me back to the past. Fear. What happened to my father when he was in the camps scared me, and it made me angry. The fact that nothing had changed and we were still hurting each other two decades on scared me too. And what do you do with all that fear and anger? Revenge is nice, but change is better. And who better to target than teenagers, who are still working out who they are and what sort of world they want to live in?

So, I set about writing Inkflower, a novel about a girl who finds out her father has six months to live and a secret he hasn’t told her about his time in Auschwitz. My father’s Holocaust story was inspiring, despite the trauma he endured. It was full of resilience, rebuilding, resistance, and strength. All I had to do was reimagine it for a young adult readership.

Taking myself out of the story and creating sixteen-year-old Lisa Keller freed me to dig deeper and create someone more conflicted about hearing her father’s story. Someone who could learn to love and accept herself and let people in. I had Lisa do the things I wish I’d been brave enough to do, like washing and feeding my father. I’d been scared so I’d avoided it. Lisa was scared of her father’s frailty too, but I made her push through that fear. She’s me, but she’s braver.

Being a teenager, Lisa isn’t afraid to feel things deeply. When you are sixteen, everything is momentous and unbearable. And so, for the first time since my father died, I gave myself permission to feel the shock of his diagnosis, and the pain of losing him. To sit with his Holocaust story and unpack it. To hold that fourteen-year-old boy’s hand and come undone.

Inkflower was a hard book to write, but there was so much that made me smile: finding a buried video testimony and a family I’d never met; sharing the lessons my father had taught me; and giving my father back his voice. He’d had it stolen twice, once by the Nazis and once by ALS. Writing Inkflower was a way for me to help him reclaim it.

My father taught me that we have to talk about the things that scare us before we can change them — a task that seems especially urgent now. And so, I’ll keep writing about the things that scare me, in the hope that one day I can transform them into something healing, something that moves us closer to a world in which we all feel safe. I think my father would like that.

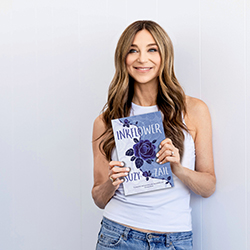

Inkflower by Suzy Zail

Suzy Zail has worked as a litigation lawyer, specializing in Family Law, but now writes full time. Among other titles, she has written her father’s story, The Tattooed Flower, about his life as a child survivor of the Holocaust. Her novel, Playing for the Commandant, about a young Jewish pianist at Auschwitz who is chosen to play for the camp commandant, was a 2015 USSBY Outstanding International Book and was honored as an exceptional book for use in social studies classrooms in the Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People List 2015.