Image by Courtney Gooch

If you’d asked me, when I was a girl, whom I planned to dress up as for Purim, I might have blinked. No one ever asked that question. I would be Esther, of course. Who else was there?

Esther was the obvious heroine of the story. The orphan turned queen turned savior of her people, which were our people, after all. So many unlikely fates and she had nailed them all! Oh — and the book was named after her. Every girl wanted to be Esther.

Beyond the main plot points, there was the matter of her character. She was virtuous, we were told. She was loyal. And she was brave — so loyal and so brave, that to save her people from genocide she dared approach King Ahasuerus without invitation, declaring: Ka’asher ovadeti ovadeti. And if I perish, I perish.

Who could beat that? Not Haman’s wife, certainly. And not the only other female character in the story: Vashti. Vashti, to begin with the most obvious strike against her, was banished almost as quickly as she appeared. Also, she seemed to be a prostitute — based on the costumes of whoever played her in the spiel — or else a leper. Either way, she was bad, and she was bad in the ways that Esther was good. Instead of virtuous, Vashti was wanton. Instead of loyal, disobedient. Instead of brave, well, it was unclear. Was it cowardice that made her refuse to parade naked in front of Ahasuerus and his friends at their party? Or was it simply a rebellious streak? Either way, she had rejected his demands. She had suffered the consequences. And her ouster paved the way for Esther — good, pure Esther; so what did Vashti really matter anyway, beyond serving as a foil for our heroine?

Either way, she was bad, and she was bad in the ways that Esther was good. Instead of virtuous, Vashti was wanton. Instead of loyal, disobedient. Instead of brave, well, it was unclear.

As a kid, all this made sense to me, not because I’d given it a lot of thought, but because I had been told the story so many times from one vantage point — the one that still dominates conventional Purim celebrations today.

Still, I thought about Vashti. There was something about her story that I didn’t quite buy, though I could not yet say what it was, or why.

Years later, I decided to investigate. And what I found, as I returned to the Book of Esther and began to read widely in the commentary, both contemporary and ancient, was that when you really looked at the text, the Esther-Vashti dichotomies that had been inculcated in me did not seem to grow in any natural or rational way from the story. Put another way, the story I’d been told about the story did not seem to match the story itself.

Wait a second, I thought. Ahasuerus is asking Vashti to do something indecent. How could she possibly agree to that, as queen? And isn’t her refusal an act of virtue? A very brave act of virtue? Why, then, has she been demonized for it? And wait a second. All these virgins Ahasuerus gathers. They’re essentially a harem. Which makes Esther a concubine. Which makes her decision to forego the other concubines’ elaborate makeup procedures more interesting. Could it be that she was hoping, even praying, that she would not be chosen as queen?

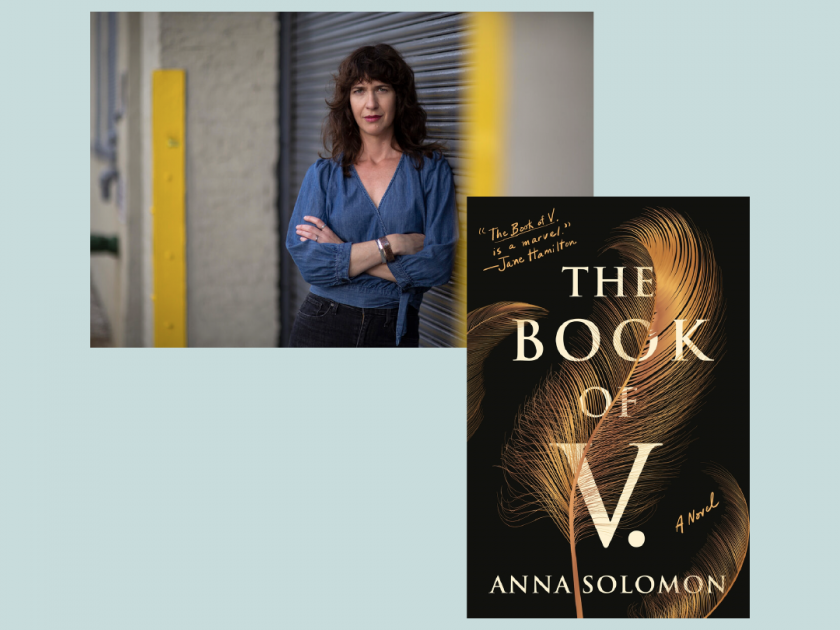

These questions and many more drove me to write my new novel, The Book of V., which reimagines and reinterprets The Book of Esther in much the same way that Michael Cunningham’s The Hours did with Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. In one thread you meet the teenaged Esther in ancient Persia and see not only what happens to her and to Vashti but how the biblical text came into being. In another you meet Vivian Barr, a senator’s wife in 1970s Washington, D.C. who is banished in much the same way as Vashti. And in the third, you get to know Lily Rubenstein, a second wife (like Esther) and mother of two in 2016 Brooklyn who is struggling with her intellectual and sexual desires, and trying to learn to sew to make Purim costumes for her daughters. The three women’s stories intertwine, and eventually collide in the present day.

I wrote The Book of V. for everyone, and I was thrilled when early readers who were totally unfamiliar with The Book of Esther said they didn’t feel they missed a beat. But I’m also eager to hear from readers who do know the biblical story. I wonder which references to the original you’ll catch, which characters will resonate most, and how reading the book will influence the way you experience Purim next year. I’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us on Facebook, our JBC Book Club page, or chat with us on Twitter @JewishBook and @SolomonAnna.

Anna Solomon is the author of Leaving Lucy Pear and The Little Bride, and a two-time winner of the Pushcart Prize. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in publications including The New York Times Magazine, One Story, Ploughshares, Slate, and more. Coeditor with Eleanor Henderson of Labor Day: True Birth Stories by Today’s Best Women Writers, Solomon was born and raised in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two children.