The Ten Largest, No. 9 by Hilma af Klint, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“Whoa,” a coworker of mine said one day in the office. “Listen to this tweet from @KylePlantEmoji!”

We gathered around her desk and she read from her phone: “Fun fact: some people have an internal narrative and some don’t. As in, some people’s thoughts are like sentences they ‘hear,’ and some people just have abstract nonverbal thoughts, and have to consciously verbalize them. And most people aren’t aware of the other type of person.”

“Is that actually true?” we wondered aloud. Most of my coworkers continued, “How could someone possibly think without using words?” — to which the rest of us, myself included, shouted, “Wait, people actually think to themselves in words?”

Given that we’re part of the Jewish Book Council team, it seems natural that — once we stopped goggling at each other in shock — our conversation turned to how our thinking styles affect our experience as readers. I’ve always gravitated toward fiction narrated in the third person, with plenty of visual detail. For the first time, I realized that this might be because it mirrors my own thought process: I picture a scene in my mind’s eye and then search for the words to articulate it. On the other hand, depictions of characters thinking to themselves in complete sentences or blurting out thoughts without meaning used to baffle me. It took effort to verbalize thoughts — how could someone do that by accident? Now I understood that these were not approximations of thoughts but a raw recording of them.

As readers, we have the enormous privilege of seeing the workings of authors’ minds when we open their books. And what about those authors? How do their thinking styles affect the way they write stories and novels? I asked eight of them to find out.

Moriel Rothman-Zecher

At a recent dinner, my sister’s friend announced that he had no mind’s eye.

“What does that mean?” we asked him.

“It means, if I close my eyes, I can’t pull up an image of my mom’s face, or a pine tree, or my childhood bedroom.”

Around the table, all of us closed our eyes and tried to picture those things.

I could, but barely. Each image was faded, wavering. That is, until I started to add in words.

Aquiline nose, graying curls, smiling mouth, anxious eyes.

Roots in the loamy ground, canopy in the summer clouds.

Glass animals arranged on a dark wooden shelf.

There we go.

I’ve realized that I have a blurry mind’s eye, but, perhaps in compensation, hypersensitive mind’s ears. The sounds of words shepherd my wandering thoughts — layer them, expand them. If I close my eyes and think “beach,” I can only vaguely summon up an image of sand and water and sky, like a stock photograph. But as soon as I add in words — fog, cliffs, sleeveless shirt, tangy smoke — part of me is transported, not to a particular beach, but to an amalgam of many different beaches, some which I’ve visited, some only imagined. Now I can not only see better what is before me (turquoise depths, foam, bright shells in the dark grit), but can also sense what is behind me (a squat row of buildings; a family with three small kids walking out of one of them) and above me (harried-looking birds, a military airplane cutting through the blue), and inside me (an old nightmare, a former love, the feeling of pressing my face into my dog’s nape).

There we go.

Dani Shapiro

When I’m between books, I walk through the world with one less layer of skin, a heightened sensitivity to everything around me. I try to be patient, to wait for an idea to present itself. After writing eleven books, I’ve learned that there’s no point in forcing it. When intimations of the next book finally appear, it’s with a sense of absolute rightness. I’m not hit by a single aspect of the book, but a thunderclap of a few seemingly disparate images, or possibly characters, or a landscape, that all seem to speak to one another. Joan Didion described this feeling as a “shimmer” and I’ve always loved that, because it has an element of the mystical to it. It’s as if the invisible becomes visible.

When this happens, I open a new notebook and begin working in longhand. I find it comforting, the tactile nature of longhand writing — the weight of a notebook, the feel of a pen. I scribble in margins, cross things out, make arrows and loops, and slowly a shape begins to emerge. Trusting this shape long before one can have any sense of whether it will ultimately work is the high-wire act.

Allegra Goodman

One day, when my son Elijah was nine, I had to run out on an errand and then circle back to take him to a dentist appointment. I told him we wouldn’t have much time, so he should be set to go as soon as I got back. He looked up from his reading and said, “Don’t worry. I’ll be ready. I’ll have one ear listening to my book and one ear listening for the car.” I smiled at the way he described reading as listening, but I knew just what he meant. I also hear the voices of books — not only as a reader, but also as a writer.

When I was starting out as a writer, I began my stories as little plays. I listened for the voice of my querulous character Rose Markowitz as she drifted in and out of childhood memories. I heard and transcribed the thoughts of her refined art dealer son Henry, and I reveled in the explosions of his academic brother Ed. As I wrote these stories, I read each installment aloud to my parents and sister to check that they heard what I heard.

Later, when I started to write novels, I experimented with narrative voice. In contrast to my satirical stories, my novel Kaaterskill Falls takes an elegiac tone. I heard the book in a voice of retrospect and consolation. My most recent novel, Sam, is from the perspective of a young girl growing up fast. The book begins when Sam is seven, and the opening line is simple: “There is a girl, and her name is Sam.” As Sam’s thoughts become more sophisticated, the narration becomes more complex.

I am a planner and an outliner, but voice is my true guide. When I begin writing, I go to a quiet place so that I can hear my characters and narrators. When in doubt, I stop to consider what my book is saying. Like my son, I bend my ear to the page and listen.

Francisco Goldman

My thoughts are usually all over the place. Whenever I read interviews I’ve given, the truth of that is embarrassingly obvious. I’ve learned by now to accept that I only really experience what people call “thinking” — that is, a sense of concentration and of control over my mind — when I am writing. For me, that has led to an enthrallment, an obsession with, a total commitment to writing and to words. My fixation is not just on seeing how the words I set down will lead to those that immediately follow them, and so on – although that is essential work. My focus is also on my intuition that something is beginning to take shape, far ahead of the words I’ve set down, or buried deep beneath them. That is what pulls me forward.

The repetitive work of wordsmithing takes place in the body as well as the mind — which might be why, when I am on the bike or the elliptical at the gym, words, scenes, and solutions to narrative problems often come to me like movie scenes. And occasionally, when I am deep into a novel, pages of written words scroll through my dreams while I’m sleeping. In the morning, I can remember a phrase or two at most, and sometimes they are like miraculous gifts.

Emily Bowen Cohen

Recently, a librarian told me she encourages reluctant readers by asking them to draw what they think a character looks like; putting the image down on paper inspires the reader to continue to think in pictures. This blew me away — it never occurred to me that anyone reads a book without imagining the story like a movie. I’m a graphic novel creator, and visualizing is essential to my writing process. Case in point: I could not write this piece without including drawings.

I’m working on a new graphic novel right now. The first step in my process was to draw my protagonist. After many false starts, here they are:

To be satisfied with my main character’s appearance, I have to understand their back story. I couldn’t grasp Kelvin’s personality until I visualized their parents. These are Kelvin’s parents.

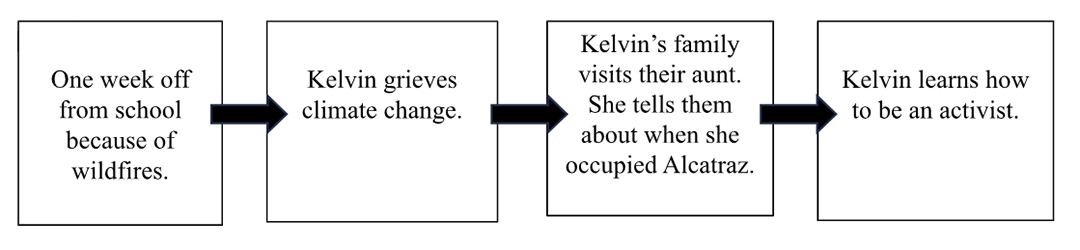

Drawing Kelvin’s family made me fall in love with them. Once characters are alive on a page, I’m passionate about finding out what kind of trouble they might get into. I map out the path of the story like a flow chart. Then I switch around the boxes until they make sense.

I add boxes with more details, take others out, and continue to change the order until I’m satisfied readers can fall in love with the character, too.

Chloe Benjamin

My mode of thinking is definitely verbal. I’ve always been an intensely narrative- and language-based person; even the dialogue in my dreams is absurdly detailed. When I’m thinking about a project, my other senses turn off. It’s easy, therefore, to live in my head.

This obsessive focus can be good for my work, but it hasn’t always been good for me. In a recent issue of my newsletter, I wrote about how chronic pain made me realize that I’d become estranged from my body, and from the fullness of life itself.

I’ve since come to value other ways of being in the world, and I’ve learned how to turn my inner monologue off and on. Once, while taking an Uber home from a writing session at a coffee shop, the weather prompted an idea for a pivotal future scene. It was overcast, with a sense of tension, as though something dangerous might happen. I’d known that this particular scene would be important, but not how I’d execute it, and that atmosphere gave me a way in; I opened my computer and started typing. Many months later, when it came time to write that scene, my notes went in virtually unchanged. I was thrilled, but not surprised: when inspiration is instinctual, I almost always find that it’s right.

For many years, I craved certainty. This is part of why I love stories — explanations! But writing is also where I most embrace mystery. I think of inspiration as a massive iceberg that forms over time: the idea is just the tip that peeks out of the water. No matter how verbal I think I am, the murk of the subconscious is deeper than language. We only know so much about ourselves after all.

Max Gross

Vladimir Nabokov described the initial inspiration for his masterpiece, Lolita, as a little “throb.” I imagine that’s the case for a lot of writers. A story starts with something small and seemingly vanishing — but powerful enough to startle its progenitor. If a plot, or a character, or an idea is truly worthy, then it’s only a matter of time before it consumes the author’s every waking thought.

Many writers start with a character and allow a situation to grow from there — but I prefer to start by thinking about an interesting situation and wondering what kind of person would find themselves in such circumstances. As the character’s edges get sanded down, the plot makes its necessary accommodations. Soon, other characters are elbowing their way into the story. The outline that I drafted when the first glimmer of the idea took hold is far too out of date to be worth revising.

I remember once being called obsessive — and I suppose this is a put-down in reference to ex-husbands or gun collectors. But as far as writing goes, I really don’t know another way.

Iddo Gefen

I sometimes think that the real reason I became a writer is because it takes me a long time to fall asleep at night. Ever since I was a child, I’ve been jealous of people who fall asleep within five minutes; it takes me at least an hour. For years I tried to find a way to pass the time, and at some point I found myself starting to ask “what if” questions about all kinds of things. What if there was a radio that read people’s minds? What if I had a dream that lasted ten years? What if there was a company that could help you find the meaning of life? Each of these questions eventually sparked a story in my collection of short stories, Jerusalem Beach.

I feel like my brain functions differently throughout the day. In the morning, my thoughts are relatively clear and organized, so this is the time I devote to editing or rewriting (although sometimes I break my own rules, and I find myself writing in the morning, too). At night, my thoughts become looser, and I have more room to run wild with ideas for stories. The problem is that I probably forget some good ideas while I sleep. So who knows, maybe I already thought of an idea for a novel that would have won a Nobel Prize, but it got lost in the wonderful moment between being awake and sleeping.

Becca Kantor is the editorial director of Jewish Book Council and its annual print literary journal, Paper Brigade. She received a BA in English from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. Becca was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in Estonia writing and studying the country’s Jewish history. She lives in Brooklyn.