This stunning, compulsively readable debut memoir tells the story of T Kira Madden’s coming-of-age in the swampy, surreal world of wealthy Boca Raton, Florida. Despite her privilege wrought from her father’s shady dealings in gambling and stocks, young Madden faced crippling loneliness and insecurity. Her drug-addled parents were frequently neglectful, strung out to what Madden calls “the other place.” Though wealthy enough to attend preparatory school and own four horses, Madden fed herself little but canned soup as a child. Her father rarely spoke to her and called her “son.” It’s no wonder that despite his physical presence for substantial portions of her childhood, Madden felt fatherless. As a teenager, she fell into codependent friendships with other “losers” who lacked solid parental support. They found a sense of control in drugs, eating disorders, and sex, both enabling each other in toxic behavior and being a loving family.

It sounds like an average “poor little rich girl” story. But Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls is much more than that, taking tropes and rendering them with an undying sense of compassion. The details of Madden’s early memories are startlingly vivid in a way that suggests she was in a persistent state of high alert, every pain etched in her brain forever. But for every mention of a terrifying drug overdose or her father leaving her at a baseball game, there are stories of her mother’s delicate removal of lice from her daughter’s hair or her father’s early teaching of magic tricks. Madden loves her family fiercely and in spite of it all, we never doubt their deep-down love for her.

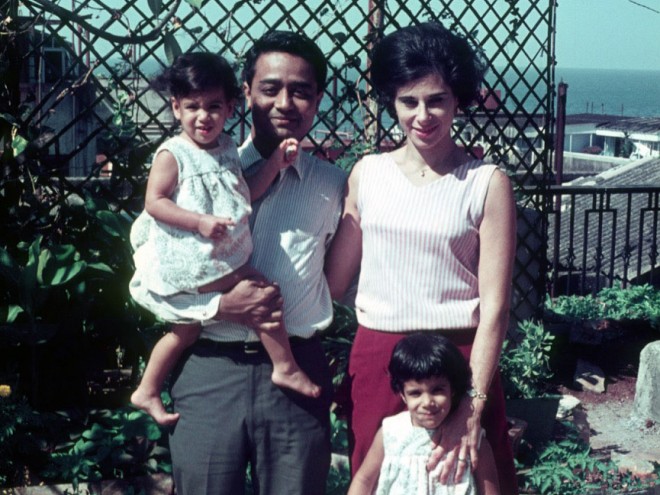

Madden delivers this all in lyrical prose as glittery as the book’s whimsical cover. More of a collection of linked essays and vignettes that jump around in time than a chronological narrative, the book treads into the murky nature of, as Joan Didion put it, the “stories we tell ourselves in order to live.” Madden gropes through the shadows of memory and research to uncover family secrets and determine who she is as a biracial (her mother is Chinese-Hawaiian and her father is white Jewish), queer girl. She tries to understand how it all fits together in order to, as she wrote in the acknowledgements, create a representational text for other children who rarely see themselves reflected in the media. But there are always loose strands. There’s invariably more — more secrets, more people, more joy and sorrow — to be uncovered. It’s a testament to Madden’s brilliance that she can take that lesson, frustrating as it might be, and still render a sense of narrative completeness from it.

Madden’s father died when she was twenty-seven, which became the catalyst for this memoir. But what security and completeness (both narratively and emotionally) she has, seem to rest most firmly on the women in her life. As good as the first two-thirds of the book are, it really shines in the final third, when Madden steps back and, through family research, DNA testing, and interviews, shows the full lives of the women in her family. These women and the tender connections between them will enable the tribe to live for a long, long time.