By

– August 15, 2012

In 1972 Mauricio Rosencof, a Uruguayan union organizer, writer and political activist, was captured by the military authorities and jailed for 13 years, 11 of them in a three-foot-by-six-foot cell.

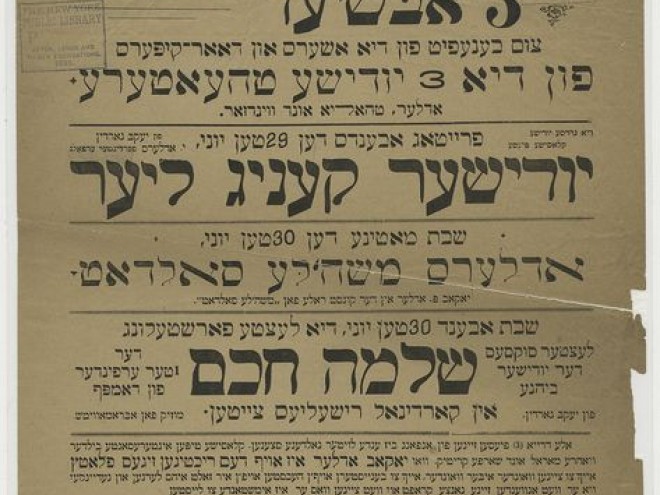

Tortured, isolated and deprived of writing materials, Rosencof wrote in his head, beginning with the letters that never came. Years earlier, the postman’s visits to his family’s house in Montevideo had brought news from the relatives still in Poland. After 1936 no more letters came. From his own living death Rosencof writes these letters, creating the numbing and increasingly horrifying news from Treblinka.

Rosencof — Moishe — had also been isolated in his own family. After the death of his teen-aged older brother, Rosencof’s mother seldom spoke or smiled; the dinner table was a place of silence. In prison Rosencof breaks open that silence, writing to his father — Papa, Viejo—-to fill in all that was unsaid between them and to forge the links and the love that connect the Poland of his grandparents — people who existed only as photographs — to him and his daughter and granddaughter, “because wherever we are, we’re together.”

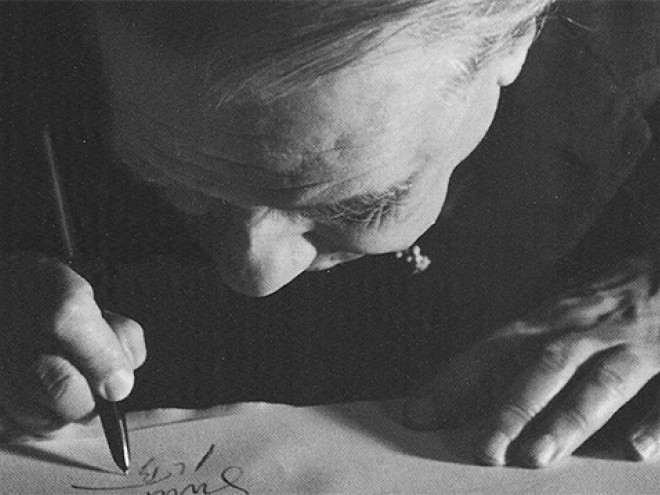

Written in 2000 and only now translated into English, The Letters That Never Came is described as an “autobiographical novel,” but it is a book that does not fit easily into a category. An eloquent meditation on suffering and survival, on the “screams that don’t die,” it is a searing indictment of any human being anywhere who lifts a hand to brutalize another. Gloss., photo.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.