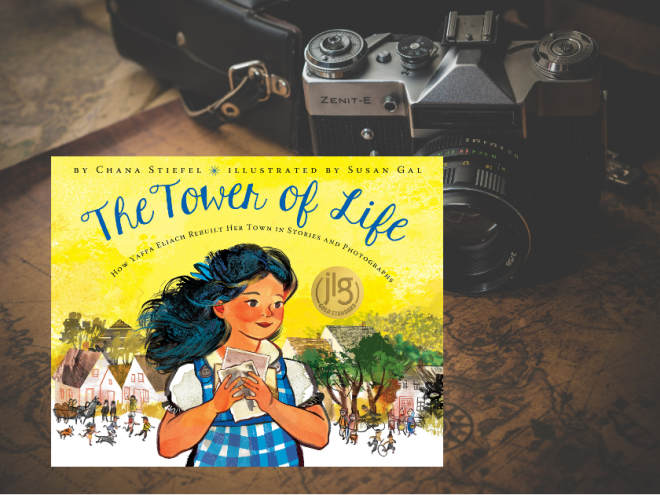

Chana Stiefel’s and Susan Gal’s The Tower of Life never mentions the term “Holocaust,” yet their new children’s picture book about historian Yaffa Eliach clearly represents the antithesis of erasure. Gearing the story to young readers, Stiefel and Gal emphasize the rich legacy of one particular shtetl, kept alive through Eliach’s meticulous documentation and her stunning exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Without denying the horrors inflicted on Europe’s Jews, the book restores the dignity of a lost civilization both by illustrating the past and calling attention to Jewish continuity in the present.

Young Yaffa Eliach is an ordinary child blessed with a loving family and close-knit community. When the book opens, she lives in Eishyshok, a small town situated in present-day Lithuania (formerly Poland). As in other books about the Holocaust for children, there is an elegiac tone abruptly interrupted by the Nazi invasion. Scenes of sledding and skating and trips to the crowded outdoor market quickly become a distant memory as the German army assaults the town, leaving behind destruction and death.

Where another author might principally focus on the family’s prewar observance of Jewish holidays, Stiefel’s approach is more subtle. She foreshadows Eliach’s future by describing communal trips to the cemetery, “where grandparents told tales of their ancestors buried beneath their feet.” These stories are instrumental in “keeping their faith and traditions alive,” and their custom will reappear later, when Eliach devotes her career to bringing her ancestors back to life. Another distinctive part of Eliach’s childhood is her grandmother’s photography studio. People seek out Grandma Alte’s bar mitzvah portraits and Jewish New Year cards, both the products of an American camera. After the war, Eliach will undertake the “sacred mission “of recovering and arranging these profound pieces of evidence for her books and, later, her exhibit.

Eliach’s family escapes from the Nazis, hiding in the forest until the Russian army liberates their home. All the while, Stiefel maintains her focus on the strength they derive from holding on to memories, and the solace Eliach finds in reading, writing, and telling inspiring stories. Although the family’s shelter is tenuous, and they are “cold, hungry, filthy, and frightened,” the book’s message is consistently optimistic. Given that Eliach ultimately triumphed in recreating the past, Stiefel paints a truthful portrait appropriate for those just beginning to learn about the Holocaust.

Susan Gal’s artwork, meanwhile, is both dramatic and accessible, an invitation to look at Eliach’s life with compassion and awe. Children will relate to the young girl in a bright gingham dress playing with her friends, and even to the scene of her desperate family quietly reading together by candlelight in the forest. Other episodes in her life will be less familiar, but Gal’s construction of a continuous visual sequence allows readers to assemble each image into one compelling picture. When the Nazis invade, the pages’ white backgrounds turn deep red, peopled with dark, faceless characters. Using watercolor, ink, and digital elements, Gal combines individual portraits, landscapes, and interiors with interspersed sepia photographs. The result is a complete representation of her subject, much as Eliach achieved in her own scholarship. A vertical two-page spread of the Holocaust Museum’s exhibition on Eishyshok is the culmination of a remarkable life — and of a book that ensures it will not be forgotten.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.