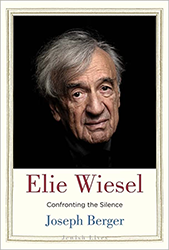

Elie Wiesel backstage before speaking to the United Jewish Appeal Convention, 1988, Photo by Michael Geissinger

Library of Congress

Had there been no Second World War, Elie Wiesel might have ended up as a Hasidic rabbi in a Hungarian shtetl, perhaps revered for his scholarly command of the Talmud and for his mystical understanding of the ways of God.

But the war transported Wiesel to realms no one could have foreseen. In its wake, he became a journalist, novelist, teacher, and orator, writing Night–one of the most essential and widely read accounts of the Holocaust. He became the torchbearer for Holocaust survivors, and won a Nobel Peace Prize for his message that eloquently condemned genocide and persecution everywhere.

How did all that come about? I was drawn to writing the biography Elie Wiesel: Confronting the Silence because of Wiesel’s astonishing accomplishments. But I was also intrigued by the idea that twists of fate, as much as a roadmap of intentions, often determine how our lives unfold.

Wiesel was born in 1928 and grew up in the town of Sighet, which vacillated between Romania and Hungary for much of the twentieth century. His grandfather was a Hasid of the Viznitz sect and Wiesel was beguiled by his grandfather’s piety and Talmudic erudition and sought to emulate him as a child. Wiesel stood out in school for his mastery of Torah and Talmud. As a teenager he was also drawn to kabbalah, showing an early flair for mysticism that colored the novels and essays he would write as an adult. Wiesel’s mother, more cultivated than was typical of Hasidic women, exerted her influence too. (She read secular magazines sent from Paris and Vienna, according to Wiesel’s memoir.)

The cozy harmony of the Jewish community of Sighet was upended during the war when German Nazis occupied the region around Sighet, angry that Hungarian officials were not sufficiently tormenting Jews. The German Nazis then confined Sighet’s Jewish population in ghettoes and ultimately deported them to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Wiesel saw his mother and seven-year-old sister walk off to what turned out tobe the gas chambers. Assigned with his father to a slave labor squad at the Auschwitz satellite camp of Buna, he saw his father starved, sickened, and beaten. After a death march to Buchenwald through snow-shrouded roads in only thin clothes, Wiesel’s father succumbed to his wounds.

Upon Buchenwald’s liberation, Wiesel was a sixteen-year-old orphan. But in an irony of fate that status proved fortunate – he could be included in a train of 400 orphans that General Charles de Gaulle of France agreed to take in. Wiesel was put up in a string of Jewish-run orphanages not far from Paris. When the time came for the orphans to strike out on their own, Wiesel wound up taking courses in literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne, idling in cafes with people in John Paul Sartre’s circle. This gave him the intellectual and literary heft that was to distinguish him.

In the collective postwar reticence about grappling with the Holocaust, Wiesel’s classic memoir Night barely caused a ripple when it was published in 1960.

Also important in shaping him was his desire to join up with the militias fighting for Israeli independence. He was rejected as too frail to be a soldier but assigned to work at the newspaper of the Irgun, one of the militias. That’s how he became a journalist, a career he pursued for the next twenty-five years that gave him a foundation to write more extensive prose, including seminal books like The Jews of Silence, focusing on the persecution of Soviet Jewry, and Souls on Fire, about Hasidic masters, and also a dozen novels.

In the collective postwar reticence about grappling with the Holocaust, Wiesel’s classic memoir Night barely caused a ripple when it was published in 1960, selling about a thousand copies a year. But the so-called miracle of the Six-Day War of 1967 set off a tidal wave of Jewish pride and a fervor to plumb Jewish identity and the Holocaust itself. Wiesel overnight became a popular speaker and Night the text that seemed to most vividly and eloquently capture the horrific experience of the camps.

Wiesel was in a way anointed as the torchbearer of Holocaust survivors when President Jimmy Carter (seeking to help his re-election campaign by mollifying a Jewish community angered by his sale of advanced military jets to Saudi Arabia) created a commission to consider building a Holocaust monument of some sort in the nation’s capital. He appointed Wiesel as its chairman. Wiesel got the committee off to an inspired start with a decision to build an educational museum focused on the murder of the six million, but he did not have the management skills to actually construct the museum.

Nevertheless, it was he who was called upon in 1985 to protest President Ronald Reagan’s decision to lay a wreath at a military cemetery in Bitburg that, it was soon revealed, contained the graves of forty-nine members of the Waffen SS, the Nazi unit which had perpetrated some of the war’s worst atrocities. Again, by a stroke of fortunate coincidence, two weeks before the Bitburg visit Reagan was to hand Wiesel a Congressional Medal of Achievement at a White House ceremony. With TV cameras recording, Wiesel responded to receiving the medal with a discreet but powerfully plainspoken rebuke of the planned Bitburg visit:

“That place is not your place, Mr. President,” he said at the speech’s memorable climax. “Your place is with the victims of the SS.”

A year following the worldwide headlines about the White House confrontation, Wiesel was informed that he had won the Nobel Prize for Peace for being a “messenger to mankind.” Although there were many other worthwhile reasons for him to be so honored, many analysts saw the Bitburg episode as finally goading the Nobel committee to award the prize he had long richly deserved for his work and words.

The Nobel was something of a Hollywood ending to a life seared by tragedy. Yet it was the cinematic and branching arc of Wiesel’s story that also filled me with confidence that a biography of this brilliant, momentous man could find an abundance of readers.

Joseph Berger was a New York Times reporter, columnist, and editor for thirty years, and he continues to contribute periodically. He has taught urban affairs at the City University of New York’s Macaulay Honors College. He is the author of Displaced Persons: Growing Up American After the Holocaust and lives in New York City.