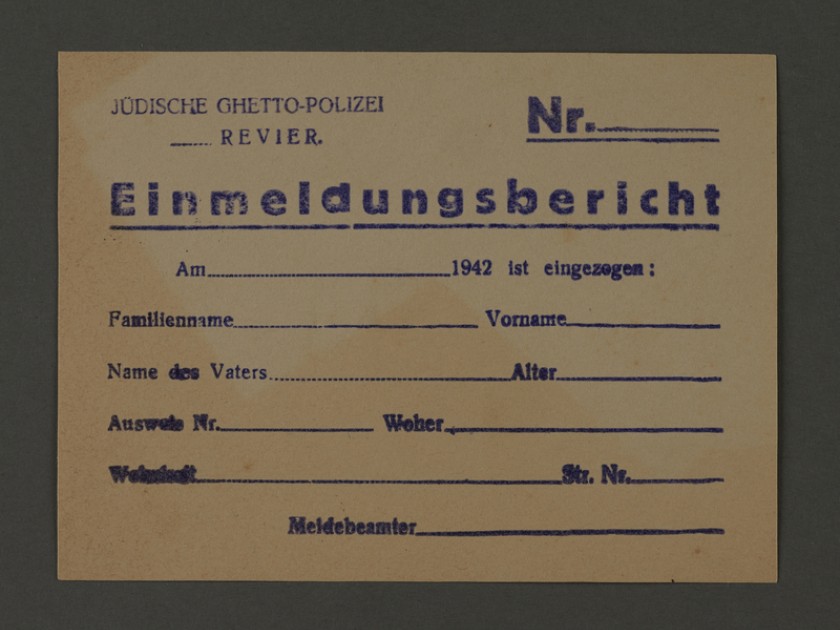

Jewish police registration form from the Kovno ghetto, 1942

What a turbulent life awaited that baby born in the Kovno ghetto! Her name was Elida, which in Hebrew means “nonbirth.” Her parents, Dr. Jonah and Tzila Freidman, chose that name in defiance of the ban on childbirth that the Nazis imposed on Jews in Lithuanian ghettos. In this sense, she was a “forbidden” child.

I was twelve when I first met Elida. She came to our family in Haifa from Vilna (Vilnius) in the late 1950s. She was a willowy girl, her eyes dark and sad, with an eagle-like nose, prominent chin, and wavy black hair. She wore plaid dresses that covered her arms and knees. Elida said little, and when she spoke, she spoke Yiddish.

I don’t remember how she was introduced to me, what she said, or what the other children of the family told me about her. We did not yet know about the horrors of the Holocaust. Whatever we knew we garnered from the whispers of adults. These pieces of information did not add up to a full story. She came to us from Vilna with an elderly couple, and I understood they were her parents. But it wasn’t clear to me why she was living with one of my aunts and not with her parents.

Several months after her arrival in Haifa, there was a mysterious commotion. The adults often whispered to each other in Yiddish. The subject of their conversation was Elida, but none of them told us, the children, anything about what was happening. Contributing to the unsettled atmosphere was the fact that my uncle Lazar, my mother’s brother, came from America, followed by his wife, Toibeh. They often spent time with Elida and pampered her with plenty of presents. A few months later, I was informed that Elida was going with them to America.

A few days after she left, I saw a newspaper spread out on the table at our house. Perhaps my parents purposely left it there for me to read. The headline was the story of a strange alliance between two jews in the kovno ghetto. The article was about a pact made between my uncle, Lazar Goldberg, and his cousin, Dr. Jonah Freidman, who swore to adopt each other’s child if only one of them survived the war.

A few days after she left, I saw a newspaper spread out on the table at our house. Perhaps my parents purposely left it there for me to read. The headline was the story of a strange alliance between two jews in the kovno ghetto.

This article sowed the seed of Elida’s story in me. I was obsessed with her name: Elida, the “forbidden” child. I clung to every bit of information I gathered about her and my uncles, and about the Holocaust. I chose to study history at the university because I wanted to understand what had happened.

Many years after the war, Elida and I met again and developed a strong and loving relationship. We first reconnected in June 1973 when she came to Israel as an immigrant, a married woman, and a mother of three children. I couldn’t know how her story would end.

About ten years ago, I set out on a journey of thousands of miles to Lithuania and the United States. Conducting dozens of meetings and interviews, I became immersed in the memories and pain of my family members. I tracked down documents, certificates, court records, drawings, and letters in Elida’s handwriting. I read books about the periods and events of her life. I incorporated the information that I gathered into the plot of this book and shaped Elida’s character as I understood it. I chose to tell the story of her life as a biographical novel.

I understand that some of my family members experienced the events differently. I apologize if I have hurt their feelings by telling the story in a way that diverges from their memories and understanding of the story. In this book, I tell the story of Elida, my cousin, as I experienced and internalized it over the years. I hope the book will immortalize her in the hearts of its readers.

Excerpted from The Forbidden Daughter. Copyright © 2021 by Adam & Eve Agencies (1995) LTD. Reprinted here with permission from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.