The Jewish Club building in Riga, Latvia, 1938

I decided it was time to investigate my Nana’s guarded past in 2017, when my son was exploring universities. She’d died when I was thirteen, taking her childhood secrets about growing up in Russia with her to the grave. Nana never spoke about why she’d concealed her Judaism when she came to Canada. When my great-grandmother, Sophie, died (she had immigrated after WWII), Nana didn’t even let my mother attend the funeral; she didn’t want her knowing Sophie was buried in a Jewish cemetery.

I could understand why Nana hid her Judaism when she arrived in Montreal, Canada, in 1938. Signs proclaiming, ‘No Blacks, No Jews, No Dogs’ were posted all over the city. The fascist National Unity Party, based in Montreal, was gaining steam under Adrian Arcand, who called himself the ‘Canadian Fuhrer.’ In 1939, Canada – like the US – turned away the St. Louis, a ship carrying 900 Jews seeking refuge from the Nazi regime. These events marred Canada’s history and Nana’s relationship with herself and her faith.

After my first child was born in 1993, armed with a notebook, two pens, and a long list of questions, I visited Nana’s older sister, Nucia, in search of answers to my questions. Nucia was an irritable chain-smoker with glaucoma who’d somehow outlived Nana by twenty years; she did not share my desire to comb the past (but she did inspire the character of Miriam in Daughters of the Occupation). In fact, she was highly suspicious of my motives. Eventually, she opened up and I left with twenty pages of notes. I also managed to get several photos of Nana as a child, many with an unidentified young man posing with the family. These images would prove to be crucial later on, pointing me in the direction of Latvia.

The first thing I noticed, when I re-examined these photos in 2017, were the names, ‘Dvinsk’ and ‘Dunaburg’ written in the corners. An online search revealed these were previous names of Daugavpils, a southeastern city in Latvia. In a subsequent census search, I learned four compelling facts. First, two of my great-grandparents, Sophie Pressman and Max Talan, lived in Daugavpils in the late 1890’s with their parents and siblings. Next, they were married in Riga in 1905, the same year they moved – bizarrely – to Siberia. Third, Max had a younger brother, Yossel, who was murdered in Riga during the Holocaust, along with his wife and two children. Finally, a number of other relatives perished or vanished during the war.

I saw my son and niece looking at the tombstone with my mother and thought, here we are, three generations together in a Jewish cemetery. We’ve broken the silence.

Author’s grandmother, father (Max Talan, seated) with Jossel Talan peeking over her shoulder. Photo courtesy of the author.

Nana never spoke about living in Riga or any family in Latvia. Yet there she was, smiling in photos with people whose names she seemingly erased from her past. Nana’s silence made me pine for what had been lost and drove me to dig deeper, to understand the people who’d shaped her identity— her parents, Max and Sophie Talan. To do this, I had to go to the country where my Jewish roots were sown. Latvia.

______

In October of 2018, I arrived in Riga, Latvia, eager to walk in my ancestors’ footsteps. It was the first time I’d set foot in a former Soviet-occupied country. Immediately, I saw how Riga was a city full of contradictions; bleak, Soviet-era apartment blocks rose on one side of the Daugava River, and elaborate Byzantine and medieval buildings flanked the opposite side.

After checking into my hotel, I met with Ilya Lensky, director of the Jews in Latvia Museum. He was able to fill in several areas of family history for me. Max and Jossel Talan were successful merchants in Riga, based in the prosperous section of the city where they had lived. Because of Max’s involvement in the Bolshevik Revolution — a march through Riga on January 13, 1905, that turned into a massacre with seventy people killed — he was exiled to Siberia. He likely married Sophie the same year so she could travel with him. That’s why Nana was born in Siberia. A devastating exile ironically saved the family from being among the 93,000 Jews murdered in the Latvian Holocaust. I was born because my great-grandparents were exiled.

This revelation was hard to digest. These twists of fate made me feel part of something larger than myself. For the first time, I truly saw how I was created by decisions made by the people who came before me.

______

The following afternoon, I was at the National Archives sifting through a stack of old photo albums and documents, assembled using ancestry details I’d sent months earlier. But everything was written in either Russian or Latvian. The stern-faced archivist made it clear she didn’t have time to help, though she did say the twenty-six people she’d included were my relations, all of whom perished in the Holocaust. This gutted me. I was beginning to understand why Nana didn’t talk about Riga or the family she’d left behind (as political exiles, they were allowed to visit Latvia).

I took photos of the documents. Headshots, passport stamps, and Cyrillic text. I was able to pick out a few handwritten names: Schlomo and Ruven. Jossel. My skin prickled when I realized Jossel Talan, my great-grandfather’s brother, was the mystery man standing beside Nana in old family photos.

______

That afternoon, I made my way to the Jewish ghetto, which , during WWII, housed 30,000 Jews within sixteen blocks. I asked the museum attendant if he could look up Jossel’s ghetto address while I toured the museum.

The museum is a former ghetto house, its walls still covered in newspapers for insulation against the arctic wind — one room on the ground floor and a loft above. Thirteen people were crammed into this shack, without running water or indoor toilets. I was struck by a wave of nausea at the thought of Jossel and his family living in such inhumane conditions.

Back at the entrance, the museum attendant explained that Jossel’s twenty-one-year-old son, Ewsey, didn’t die in the Rumbula forest or in the ghetto. He was seized by the Nazis, along with other young, Jewish men, and forced to dig up graves of Latvians killed by the Soviets. The Nazis photographed these men with the bodies, and proclaimed they were responsible; this blatant propaganda was used to ignite a pogrom against the Jews. Ewsey was shot on July 21, 1941, in the Central Prison courtyard. Nobody knows where he’s buried. The attendant also said he didn’t know whether Jossel, his wife, and daughter perished on November 30 or December 8 in the Rumbula forest.

During the Rumbula massacre, 26,000 Jews were murdered over two days in a manner and scale equal to Ukraine’s Babi Yar, yet Latvia’s Holocaust is not part of the traditional narrative. Both massacres employed mobile death squads — Einsatzgruppen — to shoot Jews in pits. Both took place in the Soviet Union in 1941, before gas chambers were used. And – because Stalin famously refused to sort the dead based on ethnic origin – victims of both massacres weren’t acknowledged as Jews until 1991, after the fall of the Soviet Union. Stalin refused to admit Jews were being targeted. By his logic, if he’d fought antisemitism, then the Soviet government would be supporting the basic premise of Nazi ideology — that Soviet rule was the rule of Jews.

Latvian Jewish survivors, however, have not forgotten the trauma they endured. Every year, they travel to Riga to honor those murdered and to speak out against antisemitism. Meanwhile, another group of people have held an annual parade since 1990 to honor Latvia’s SS Legion, created in 1943 and controlled by the Nazis. Jewish groups worldwide have condemned the event, saying it celebrates Hitler and collaborators involved in the destruction of the Jewish community during the Holocaust. In 2022, hundreds took part — including veterans revered as heroes who fought the Red Army for Latvia’s freedom.

Still, the Latvian Holocaust remains unknown globally. This riled me, especially when I stood before the mass graves at Rumbula to honor and remember those murdered. That was the moment the seeds for Daughters of the Occupation were planted.

When I returned home, I took my mother, son, and niece to see Sophie’s grave in a Jewish cemetery in Montreal. Two menorahs, carved into the top corners of the stone, proudly declare my great-grandmother’s faith. I thought of Riga and the mass graves; Jossel and his family; Nana, alone with her secrets. I saw my son and niece looking at the tombstone with my mother and thought, here we are, three generations together in a Jewish cemetery. We’ve broken the silence.

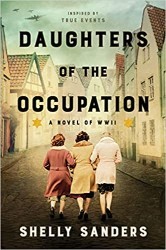

Daughters of the Occupation by Shelly Sanders is out May 3rd 2022

Shelly Sanders is the author of Daughters of the Occupation (Harper, 2022), a Canadian bestseller for four weeks. The novel is inspired by the discovery of her Jewish roots as an adult, and by her grandmother’s family, many of whom were murdered during the Latvian Holocaust. Carol Memmott, of the Washington Post, says this “haunting novel refers not only to the victims of Latvia’s Holocaust but also to their descendants, who carry the trauma of their ancestors.”

Shelly is also the author of three Young Adult historical fiction novels (The Rachel Trilogy, Second Story Press); the first received a Starred Review in Booklist, and two of the three were named Notable Books for Teens from the Association of Jewish Libraries.

Follow Shelly on Twitter @shelly_sanders and on Instagram: fictionbyshellysanders