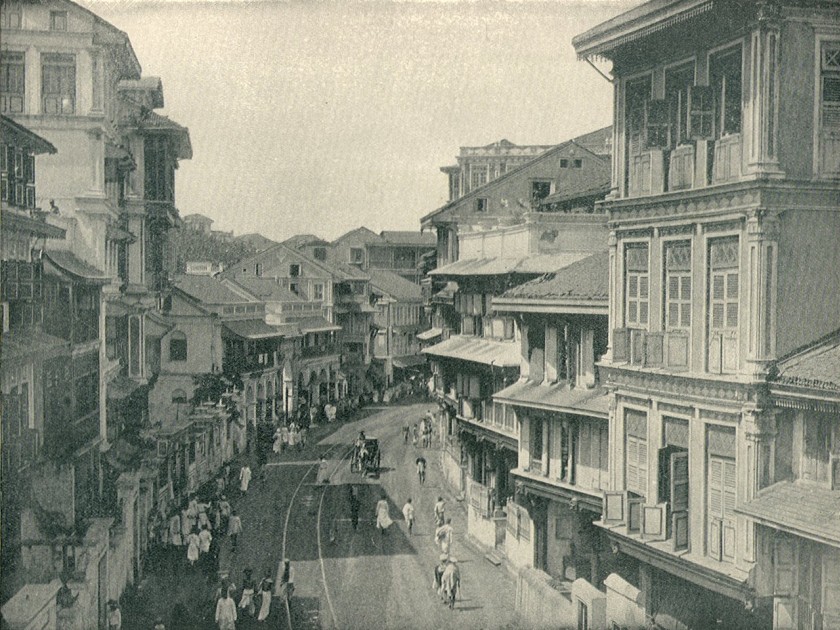

Bombay, 1890

Facing persecution, discrimination, and violence in the world, Jews have found safety in India for over 2,000 years. In Kochi, Mumbai, Pune, Kolkata, and Delhi, men proudly donned kippahs on their heads. Kosher shops displayed Magen David in their windows with zeal. Street signs pointed the way in Hebrew. Is it any wonder, then, that when fleeing the Nazis, five thousand Jews sought refuge in the land of sandalwood, silk, and peacocks?

And yet, it was a surprise to me. I’d never heard of Indian Jews.

As an Indian American writer of historical fiction, I begin with research about the time period, the people, and the political climate of my story before layering in elements from my imagination. My upcoming novel, Six Days in Bombay, inspired by the free-spirited, scandalous 1930s painter Amrita Sher-Gil, led me to research her life and work in both Europe and India. I found out that Sher-Gil’s father was an Indian scholar and her mother was a Hungarian Jew. I wanted to weave this into my novel and modeled the character of Mira Novak after Sher-Gil, but I altered Novak’s parentage to a Czech Jewish father and a Hindu mother. Since the real Sher-Gil family had moved from Europe to India, the fictitious Novak family needed to relocate from Bohemia (as the Czech Republic was known in 1937, the year the novel takes place) to Bombay (now Mumbai). Now I had to answer this question: why would a Czech Jew move to Bombay in 1937? Down I went into a rabbit hole about the history of Jews in India.

Renowned Indo-Judaic scholar Dr. Nathan Katz has written extensively about three distinct communities of Jews in India. The Cochin Jews, believed to be the oldest group, were merchants and traders, dealing in commodities like timber, coral, and spices. They’d settled along Kochi in Southern India, working the land, running coconut plantations, and specializing in the building trades.

The Baghdadi Jews, so-called because they spoke Arabic and Persian languages, bought and sold textiles, jute, and indigo. Joseph Sassoon wrote about his famous Baghdadi Jewish family (The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire) who amassed copious wealth exporting opium and cotton to China for the British before branching out into building ships and factories, and founding hospitals, schools, and libraries along the way.

Fleeing persecution from the Galilee region, the Bene Israel community were initially farmers, carpenters, and oil pressers in India. Many went into the British Military and were given government roles during British rule. A few in the community entered politics.

Each of these communities have lived in harmony in India. Jews assimilated into the majority citizenry while maintaining a distinct cultural identity. They learned the local languages, adopted traditional cuisine and dress and contributed to the region’s economic and social progress. At the same time, they built synagogues, ritual baths, kosher butchers and bakeries, Jewish Community Centers and Hebrew schools. Dr. Katz was astounded by the ease with which these Jews moved about in India, as comfortable in their Jewishness as in their Indianness. He found no word in Hindi for antisemitism. It made him wonder: what would it feel like to be a Jew without the fear of persecution?

At a time when Hindu and Muslim women were forbidden from performing in public, Jewish women became national icons in Bollywood.

Despite their minority presence in India — some estimates put the Indian Jewish population at 30,000 and others at 50,000 at its height — they had a large influence in certain cultural arenas, most notably in India’s film industry. At a time when Hindu and Muslim women were forbidden from performing in public, Jewish women became national icons in Bollywood. Indian audiences couldn’t get enough of silent-era stars like Sulochana (born Ruby Myers), or talkie stars Pramila (born Esther Abrahams), Uncle David (David Abraham), and Nadira (born Florence Ezekiel).

In his film Shalom Bollywood: The Untold Story of Indian Cinema director Danny Ben-Moshe highlighted Jewish talent behind the camera as well: writers, directors, cameramen, musicians, and producers. Indian Jews traveled to Hollywood to learn film techniques and brought their skills back to Bollywood. By 1930, Jewish executives were running six of the eight major studios.

Today, only 5,000 Jews remain in India. But in the 1937 world of my novel, the Novak family is thriving in Bombay and we see the vibrant Jewish community they join in India. Amrita’s father abandoned his prosperous Czech glassworks factory for the safety of Bombay and her eight synagogues before Hitler could storm Prague Castle. Mr. Novak has raised funds to build a new synagogue and coaxed the lovely Sulochana (Ruby Myers) to perform the ribbon cutting ceremony. In contrast, the father of Mira’s childhood friend — Petra Hitzig — believed his business dealings with the Germans could save his family from being sent to a concentration camp. However, his decision has tragic consequences as the Hitzig family find themselves being deported to Terezin; in real-life 75,000 Czech Jews were displaced and forced into this camp.

In Prague’s Pinkas Synagogue I came upon a small room filled with drawings of young children from the Terezin camps. A young woman there had rounded up scraps of paper, chalk, and pencils to keep the children busy, drawing happier times in their lives: a birthday celebration, a family dinner, an afternoon at the playground with their friends. In Six Days in Bombay Petra Hitzig became that courageous and hopeful woman. My vision blurs even now, thinking about those children — the drawings depicting birthday cakes and happier times.

My new novel, Six Days in Bombay, draws on the history of the Second World War, as well as 2,000 years of Jewish culture and community in India. Weaving together these stories of resistance, survival, and luck across time and continents, these characters offer up a piece of Jewish history too often overlooked.

Six Days in Bombay by Alka Joshi