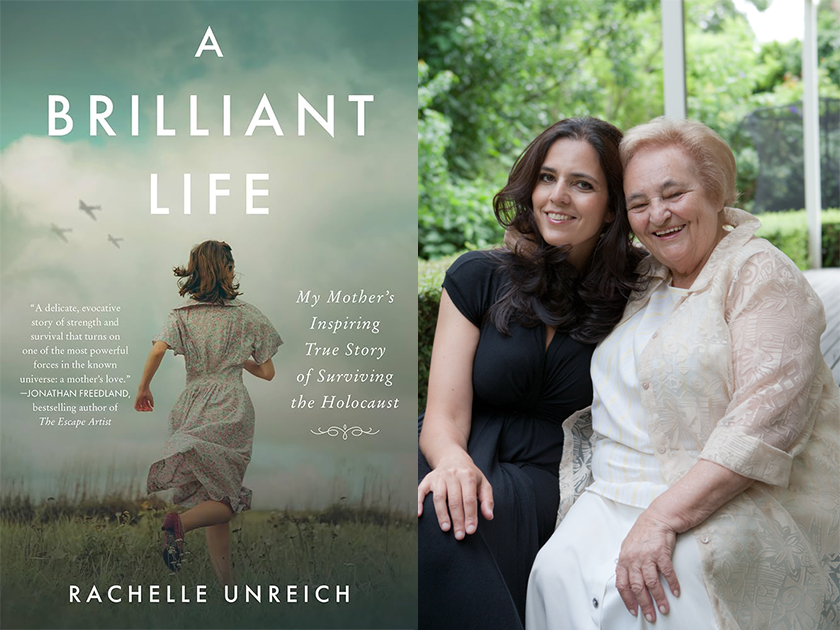

Rachelle Unreich and her mother, Mira, Photo by Vicky Leon

All photos courtesy of the author

At the heart of the memoir I wrote about my mother, Mira—A Brilliant Life: My Mother’s Inspiring True Story of Surviving the Holocaust—was a series of interviews I did with her in the last six months of her life.

I didn’t plan to interview my aging mother, whose stories I thought I knew so well already. She was an enthusiastic conversationalist, which is not to say that she talked all the time, but rather that when questions were posed to her, she would compose her answers impressively. She did not ramble or go off topic; instead, her stories contained entire worlds rendered with the most evocative details. My mother’s memories floated around in my own head for some time after our interviews. There was the time her father, Dolfie, prodded her shy mother, Genya, to sing in front of an audience, prompting twin spots of blush to color her cheeks — “like paprika,” recalled Mira. Or the story of when her two brothers played a game of cops and robbers that devolved into fisticuffs, making Genya cry — the only time her children had ever seen her do so. They would never fight again.

Mira and Rachelle

But it turned out, I didn’t retain Mira’s stories as well as I had initially thought. Although I knew she was born in a tiny postage-stamp of a village, Spišská Stará Ves, in Czechoslovakia in 1927, I could summon up only the sketchiest of details about how she lived there. She was twelve when war broke out, and seventeen when she was sent to the first of four concentration camps that she would endure — among them, Auschwitz. As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, I knew that I had a responsibility to remember her stories accurately.

Still, despite the fact that I’ve been a journalist for three and a half decades, it wouldn’t have occurred to me to interview her at the end of her life if my brother hadn’t suggested it. Mira was eighty-nine, and ovarian cancer had robbed her — and us — of so much. Gone was her singsong voice, which her children were so accustomed to hearing in phone calls each morning. It was replaced with a flat drawl, and that flatness permeated every other part of her. The light behind her eyes was dimming; the pallor of her skin had lost its shine. Every day, the things that I’d thought were her trademark — her vibrancy, her color, her joy — faded more and more.

At first, I was interviewing her to distract her, not to gather material. And so I started casually, maybe even carelessly. “What did you eat for breakfast when you were little?” I asked. “Did you have any pets?” But soon my questions became more nuanced. “What did your parents try to teach you? Did they have a good marriage?” I had never known any of my grandparents, since all four of them were killed during the Holocaust. But the more Mira talked, the clearer the picture that emerged. My maternal grandfather, Dolfie, was not only practical and resolute, but also a gifted violin player with a mellifluous voice. When he sang traditional hymns on the Sabbath, said Mira, “the walls would be shaking.” She told me that she could not have imagined any concert ticket rivaling the music that was performed in her dining room on those evenings. My maternal grandmother, Genya, was soft-spoken but maintained a quiet determination. Her secret talent lay in sewing, in her ability to combine fabrics and colors to create garments of great originality and beauty. Decades later, Mira would inherit this gift, and her love of clothes would lead her to be feted for her wonderful style. Once, when she was in her thirties and living in Australia, Mira wore a tightly fitted black dress to a ball held by a Jewish organization. It had a giant bow that covered almost the entire back of the dress. For years afterward, people would come up to her and tell her how beautiful she had looked.

Sometimes, we spoke about what happened to her during the Holocaust. There were many segments that I knew already, since she had completed three recorded testimonies by then. But somehow, by sitting down with her and listening — really listening — I heard these stories differently. Our conversations had knitted a new intimacy between us, and I now knew not only what she had been through in her life, but also who she was as a person, and how she felt. It made me wonder: how often do we neglect to find out who our parents really are? I had not done this with my father, and I think about all the questions I might have asked him. What did you hope for in life when you were growing up? What did you most regret? What was the lesson you most wanted to pass on to me? What is your favorite memory of the two of us together?

I wish someone had taught me earlier everything I eventually learned from interviewing my mother. Once a person is gone, there is no filling in the gaps. Finding out who a person truly is — not just who they are to you — will enrich you, and will allow you to cobble together the jigsaw puzzle pieces of your own life. For example, by speaking this way with Mira, I understood why she had responded to my adolescent crushes with faint discouragement. I realize now that she did not understand them; perhaps she was even scared of them. She had missed out on her entire teenage years, and had no inkling of what they could have been. For the first time, I could look back on my own time as a teenager who thought her mother didn’t understand her, and I could forgive myself, too.

I hadn’t known that I could fill my mother’s final months with something poignant and meaningful, and — much to my amazement — something dotted with real joy. So much of that time was ugly: the medicine she had to take, the wretchedness of her illness as she deteriorated. But, as I wrote in my book, A Brilliant Life: “Through the veil of her sickness, past the nausea and her swollen belly and her achiness, we were sharing moments of such beauty, I would feel dazzled by them afterwards. It was as if we had somehow managed to sneak off and have a mother-daughter holiday, one where we had spent the days laughing and crying and, most of all, loving each other fiercely.”

Mira and Rachelle in 2000

Photo by Andrew Lehmann

Rachelle Unreich has been a journalist for thirty-eight years, including seven years in New York and Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in publications including Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, Rolling Stone and the Sydney Morning Herald, and she has been published extensively in the United States, UK, South-East Asia and Australia. She lives in Melbourne, Australia.