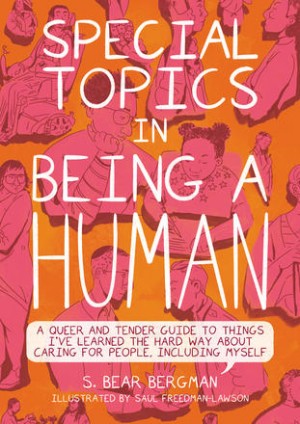

Today, in honor of International Transgender Day of Visibility, we hear from S. Bear Bergman. Bergman is an author, storyteller, and educator working to create positive, celebratory representations of trans lives. Recent or current projects include two fabulous children’s storybooks featuring trans-identified kid characters, a performance about loving and living in a queer/ed Jewish family titled Gathering Light, teaching pleasure-positive trans/genderqueer sex ed, and his sixth book Blood, Marriage, Wine & Glitter (Arsenal Pulp, 2013). He is blogging here today for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

For a while, just as Transgender Day of Remembrance was getting established as an observance, a competing movement emerged. That competing movement, well-intentioned but wrong-headed, had the following idea:

For a while, just as Transgender Day of Remembrance was getting established as an observance, a competing movement emerged. That competing movement, well-intentioned but wrong-headed, had the following idea:

“Trans Day of Remembrance is a sad and depressing situation. We mope around mourning our murdered community members, and if that’s our only public observance it makes non-trans people think that transgender lives are only and ever nasty, brutish, and short. Instead, let’s take the day and make it celebratory! We’ll have a dance and a film screening and maybe a sexy party!”

Communities battled over this, and the source of the battle was people’s feeling that mourning and celebration were opposite to one another. With some time to reflect, I have been able to understand that this is a way that my Jewish values inform and infuse my understanding of the world so completely that sometimes it takes a while for me to notice why I don’t quite grasp some piece of mainstream, Christian-inflected, thinking.

Coming from a tradition in which the prayer we say for dead people mentions exactly nothing about death but has to be said every day for a year, and whose mourning rituals involve both profound self-abnegation and constant food and family, it’s no wonder I might be slow to understand. Jewish mourning is complex and communal; it invites us into a long contemplation of the dead person and their place in the world, now emptied.

For the record, I stand philosophically with those who wanted Trans Day of Remembrance to remain a separate observance, in November. I supported the creation of a separate day to celebrate the lives and achievements of transgender and transsexual people: International Transgender Day of Visibility, in March. I don’t think TDOR is a good day for a drag ball or a cross-campus kickline. It’s a day to remember who we’ve lost: mostly trans women, and of those mostly trans women of colour, who have been brutally murdered because someone heard something or saw something that outed her as trans. But since we don’t usually know the people we’re mourning – never all of them and usually not more than one of them – it becomes difficult to celebrate. We don’t have a sense of what space they’ve left behind; we can’t celebrate the dead. All we can do is add glitter and attempt to look cheerful.

When my Grandpa died, we sat shiva for him. I was grieving and behaved like grieving people tend to: mercurial and slightly irrational. I wasn’t hungry at all until I was ravenous, I was crying except when I was feeling so grateful to be with my family and friends. I heard new stories about him and told stories that were new to other people; I gorged myself on bagels and lox on the back deck with my brother well past dark after not having eaten all day. I accepted and wore the cufflinks of his that grandmother gave me, and wore them with satisfaction, and rubbed my thumb over them repeatedly as I tried not to cry. I held hands with my grandmother a lot, and tried to cheer her up enough to get her to eat a little. We talked about the recently-dead, and how he would have felt about each food or person or circumstance, practicing our past tenses and taking a lot of deep breaths.

By the end of the week, we were all doing a little better. I had told all my favorite stories about him (should we meet in person, ask me about my Grandpa and the kippers a week before D‑Day) and missed him both less and more. I had mourned and celebrated, both.

In my most recent book, Blood, Marriage, Wine & Glitter, there’s a chapter about Chanukah and Transgender Day of Remembrance, about resistance and sadness and joy. Since writing the book, I have started to understand both why and how both observances are more complicated than a dichotomy of “this is the happy trans observance” and “this is the sad trans observance,” even though that’s how they’re sold to the public. In fact, Remembrance must include not just the fact that our sisters and brothers are dead but who they were, what they wished and loved and made, what they left behind and how we are enriched by it. And Visibility must include who is dead and why, and who will miss them and how we are responsible to those people they’ve left behind.

All of these stories are complicated; our observances must be complicated to be appropriate and relevant to our work. Otherwise, we’re stuck in a happy/sad dichotomy that serves nothing. This year, on International Transgender Day of Visibility we have much to celebrate: the emergence of Janet Mock and Laverne Cox as role models in the national scene, successful court cases in several US states and Canadian provinces that give young people the right to participate in activities in their identified gender, new artistic work by writers and artists from across the gender spectrum and beyond its reach, and much more. And we also have things to mourn, ranging from legislative defeats to community suicides. There has to be room for all of them.

All of these stories are complicated; our observances must be complicated to be appropriate and relevant to our work. Otherwise, we’re stuck in a happy/sad dichotomy that serves nothing. This year, on International Transgender Day of Visibility we have much to celebrate: the emergence of Janet Mock and Laverne Cox as role models in the national scene, successful court cases in several US states and Canadian provinces that give young people the right to participate in activities in their identified gender, new artistic work by writers and artists from across the gender spectrum and beyond its reach, and much more. And we also have things to mourn, ranging from legislative defeats to community suicides. There has to be room for all of them.

Today, for International Transgender Day of Visibility, I am happy to be out as a queer, transsexual Jew, as a husband and father and daughter, as a person who is working professionally to increase understanding and awareness about transgender issues and hopes someday to do himself right out of a job. If you’re able, join me in observing ITDV by seeking out the cultural or artistic work of trans-identified people where you live — and making a note, in November, to say the names of our transgender dead aloud in shul during the week of Transgender Day or Remembrance. It may be that we can separate our celebration from our mourning, but I don’t believe we should.

Read more about S. Bear Bergman here.

Related Content: Jewish GLBT Reading List

S. Bear Bergman is an author, storyteller, educator and the founder and publisher of children’s book publisher Flamingo Rampant, which makes feminist, culturally-diverse children’s picture books celebrating LGBT2Q+ kids and families. He writes creative non-fiction for grown ups, fiction for children, the advice column Asking Bear, and was the co-editor (along with Kate Bornstein) of Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation. These days he spends most of his time making trans cultural competency interventions any way he can and trying to avoid stepping on Lego.