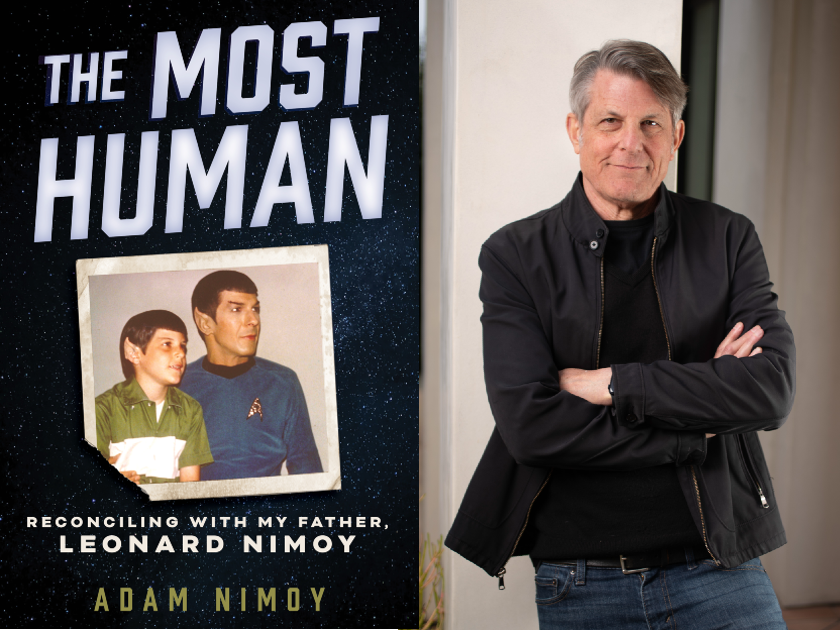

Author photo by Jonathan Melnick

“The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” This famous quote uttered by Star Trek’s Mr. Spock was one of the main threads of my conversation with writer and filmmaker Adam Nimoy, son of the actor who played the beloved character. In his memoir, The Most Human: Reconciling with my Father, Leonard Nimoy, Adam Nimoy describes his lifelong attempt to connect with his father, a man so revered by the public but often detached and troubled at home. Two men, both struggling with substance abuse, both going through divorce and new marriages, both trying to do what was best for their children. The Most Human is just that — an incredibly human story, teaching us how to accept the people in our lives for who they are, imperfections and all. For the benefit of those in his life, Nimoy had to learn how to accept people as they are. This memoir lovingly details the intertwined lives of two men, Torah, and intergenerational healing.

Isadora Kianovsky: Thank you so much for meeting with me and for sharing this really powerful story of your life and your experiences with your father. Opening up about family in particular is so personal and intense for a lot of people, and especially you because your father was so well known as an actor, a character, and a public figure. It has been really interesting to hear about all sides of this iconic person. I want to start off by asking what inspired you to write this memoir? Was there a specific event or moment that led you to get started on it?

Adam Nimoy: I produced a documentary on my dad, For the Love of Spock, in 2016. It was something that I was creating with my dad to celebrate Spock, specifically. I came up with the idea because 2016 was the fiftieth anniversary of the original air date of Star Trek. When my dad died in 2015, it became clear by the outpouring of emotion about him that we needed to include not only the life of Spock, but the life of Leonard Nimoy: the actor, the humanitarian, the Renaissance man. And while we were making the film, many people who were involved or who I was talking to and consulting with were pretty emphatic that I should also be focusing on a third aspect of my father’s life. And that was my journey with him, my relationship with him. Because it started off as very problematic when I was young. It blossomed into a lot of conflict when I was getting older and I was pretty much lost in a cloud of marijuana smoke. And my dad was deep in his alcoholism, which fueled a lot of the conflict between us.

And then he went sober. I found twelve-step recovery, too, and we were able to — using the tools of recovery — find a way to reconcile with one another to the point where we had a very close and loving relationship the last years of his life. One of the examples was when we went back to Boston in 2013 to chronicle his memories and really to emphasize the trajectory of his life from the son of Ukrainian Russian immigrants.The trajectory of coming out of that West End tenement of Boston and becoming this iconic figure that’s known all over the world. In the twelve-step meetings I go to, we share what our journey of recovery is, and that’s been the defining relationship of my life. And when I share that story, I get a lot of people afterwards who come up to me and say, “I’m experiencing the same thing. Thank you for sharing your experience with your dad, because I’m going to call my dad tonight and see if I can find a way to reconnect.” It’s a story that resonates with people because it’s a human story, it has nothing to do with my father’s celebrity.

So I really felt that I wanted to write something. I’ve always been a writer. I started off kind of resisting the Leonard aspect of it because I wanted to do something that was of my own. But Leonard’s story is my story as well. We’re deeply intertwined with one another. I also talk about my recovery and relationship to my mother, my ex-wife, my children — in particular, my teenage daughter, Maddy — and how recovery helped me with those relationships.

But the key — the granddaddy, the mother of all resentments or difficult relationships that I had — was with my dad, and because it resonated with people, it felt like I should just delve deeper into it in the book and share that part of my story.

IK: Thank you. It really was such a powerful look, and I think a lot of people, like you said, could relate to it. I think people don’t always talk about these resentments or family dysfunctions. But I think it is something that people need to know, that everyone has their own struggles with family and that doesn’t make it wrong, or the relationships bad. It just means that they need work and time.

You mentioned you’ve always been writing, but I know you’ve done a lot of work specifically within the realms of film and television as well. Is there a reason that you specifically wanted this story to be told as a written memoir?

AN: My journey was really about creating my own path and my own identity. I had the ability, the interest, and the drive to get through college and law school. I thought that was going to be it for me. I wanted something that was intellectually stimulating and of interest. But it became clear to me after seven years of law practice that it was not going to be that stimulating for me. There’s a lot about practicing law that is very rote and mundane — you’re going to be working isolated at a desk all day. The fact is that filmmaking is a much more collaborative art form, and I wanted to do something that was more creatively stimulating for me.

I’ve been journaling all my life. There’s dozens of journals back here that I’ve collected. I did want to, in essence, follow in my father’s footsteps, to express myself creatively — and storytelling, which, for me, is tied to the Bible, it’s tied to the Old Testament. Spectacular storytelling in terms of Torah. So, when I came around to wanting to write the memoir, particularly in terms of my dad, it was another way of processing what my experience was with him. This is the thing about art, and I learned this from my dad, and in other classes about storytelling — the more specific you are about relaying your experience, the more vulnerable and honest it is, the more universally it resonates with other people It’s not therapy, but it’s not too far away from therapy. Because you are going through these things, these episodes, in your mind, and you’re looking at them and you’re trying to understand — what is the significance of these episodes, which episodes should I include? How much do I tell about my dad and what do I not say anything about?

I do spill some blood on the page in my book. But I’m not telling everything. I’m telling what I think is important, but also being mindful of the fact that my father is revered by millions of people all over the world. They don’t want to hear him being trashed. There’s purpose to what I’m doing. I tried to portray some of these problems I had with my dad as fairly as I could without pointing fingers and laying blame, because recovery is really about focusing on our own contribution to the problem. I do still want to be honest about some of the things that happened, because it makes the reconciliation that much sweeter and more powerful. And that is really the point of the book.

IK: To me, Star Trek has always existed within the realm of family. My grandma is a massive fan – Mr. Spock, of course, being her favorite character. It’s through her that I came to know the show and its impact. Star Trek is so deeply intertwined with your own family life, so I am curious if you want to talk a little bit more about the contrast between the global perception of Star Trek, Spock, whatever that means to you, versus your own personal experience. What was that shift like?

AN: It’s interesting that a lot of people talk about the intergenerational experience of watching Star Trek with a parent or a grandparent. It’s a wonderful thing when you can share and find something that you can connect to with other generations in your family. I did it with my son in terms of music; I mean, I just brainwashed that kid and now he’s traveling all over the world in a rock band. And I connected with my dad in terms of his work because I was a sci-fi-fantasy fan to begin with. So when Spock came around, I was old enough to know exactly what was happening and how exciting it really was. (Thank God I was old enough to know that.)

But in terms of the other ways that Star Trek and Spock resonate in the world, the philosophy behind Gene Roddenberry’s vision is one of a positive future: humankind is going to be okay; we’re going to achieve [and] overcome some of our challenges on planet Earth, and we’re going to ally with other planets and continue on through the galaxy spreading the word that we should all get along. It’s a big umbrella, which, for me, is the tradition of Judaism: that we should all be tolerant of one another, that we should welcome the stranger and take care of the widow, the orphan, and the poor. That’s what Torah is to me.

IK: Tikkun olam.

AN: Tikkun olam—heal the world. It’s that simple. Star Trek just furthers that message, and that is what appeals to so many other people who are fans of the show. Spock in particular – it’s this whole idea of being the outsider. I hear this again and again. That Spock is different. Spock’s the nerd in all of us, you know, the outcast, the weirdo. And I’ve had that experience very much myself. That is Spock’s experience. Because the thing that my father reminded me of very late in his life, while we were making the documentary: Spock is the only officer on the Enterprise’s bridge who was from another planet. And as a result of that, his objective for his character was how he can integrate himself for the good of the whole, to give the best of himself. And it works, I mean, he really does give everything he has for the benefit of the mission. He’s always dedicated and loyal to the crew and the captain.

But this is what people don’t really know or understand: that is Leonard’s story. Because Leonard was born on the streets of Boston, a tenement neighborhood comprised of Russian Jews, Irish and Italian Catholics. His parents came as immigrants, out of desperation for a better life. So his objective for the trajectory of his life is much like Spock, as an outsider. How can I integrate myself with society as a whole? How can I give the best that I have to offer of myself and achieve success within that society? And that is what inspired him and drove him to pursue his dream. He had to struggle and survive on his own. So when the role of Spock came along, he knew exactly how to play that role, because it was the story of his life.

IK: I’d like to go back to some of the things that you mentioned about Torah, storytelling, and Jewishness, and how this all relates. Your book is a story about intergenerational links and patterns, and I thought it was so fascinating how you traced it all the way back to the beginning, this parallel between your father being Abraham and you being Isaac during the Akedah. Could you speak more on how you use this motif and how the use of biblical allusion in your story influences your own Jewish experience?

AN: In recovery, we are taught not to take anything personally. That people do things for different reasons even the stuff that happened with my dad. My mom would say, “As hard as he is on you, he’s hardest on himself.” And that, when my dad would get difficult, more often than not it was because something else was going on with him.

In Torah, we do take things personally. It’s our story. It says you were slaves in Egypt; you were at Sinai; when you received the Ten Commandments in the presence of Moses, in the presence of God. That surpasses all the generations. That’s you and me. We were there. And if we don’t take it personally, then we don’t really harvest the incredible impact of what it means to be on this planet. We bring all of our intergenerational experience with us to this given moment — the good and the bad. And that is really what I’m trying to touch on, because The Most Human is not a book specifically catered to the Jewish community, but I am a Jew and I am steeped in Jewish tradition, as was my father.

And there are instances where my life is an echo of what’s happening in Torah: The Binding of Isaac is that story. I felt, sometimes, when we were in conflict with each other, like I was there on the bier with the wood, tied up. The binding of Isaac is the binding of Adam. So it’s not just the binding of Isaac, it echoes on through the family tree.

So this is the question of our tradition: how do we break the cycle? Where’s my free will? God gave us free will; Torah is the manual on how to use it. And for me, the answer to all of these questions came through the miracle of twelve-step recovery. We can’t change the past. We can recreate it and what it means. Rabbi Mark Borovitz, with whom I study Torah, once told me, “When you make amends to your dad, you’re making amends for Abraham and what happened with Isaac. You’re making amends for all of us.” It’s that powerful. And you have to see it that way because then everything becomes more meaningful, more symbolic.

This is one of the many ways that Jewish tradition has informed my life and my writing. And the other thing going through my mind is the role of women in Torah — in Exodus in particular, it’s the women who set the story in motion. That is what’s happening in my book, because I needed the challenges of relating to my Jewish mother, my ex-wife, and my teenage daughter. I needed to learn how to use my recovery tools in repairing my relationships with them in order to be ready for the mother of all resentments and troublesome relationships, that of my father. So there’s so many echoes. And that’s why I love studying Torah.

In Torah, we do take things personally. It’s our story… And if we don’t take it personally, then we don’t really harvest the incredible impact of what it means to be on this planet.

IK: You mentioned the relationships with the women in your life, specifically your mother, your ex-wife, your teenage daughter. I thought that the way that you wrote about these three relationships in particular were really important. Anyone who’s been through divorce in some way can sort of see themselves in what you write about. It’s not an easy thing to discuss publicly, but I thought you were really insightful. Writing the book, you spent a lot of time trying to also understand what the people in your life were feeling in any given complicated situation. Can you speak a bit about the experience of writing about these intimate relationships?

AN: The divorce thing is tricky because it’s also a challenge about recovery. The focus has to be on yourself. I had the benefit of the following: My ex-wife Nancy and I agreed that what was best for the kids was really going to be the objective. And we had a lot of skirmishes; there was a lot of back and forth. Nancy’s a very strong willed individual, and I’m attempting to be even handed about the way I write these things. These are things I learned from other memoirists and other writers, which is to just give the information. Don’t pass judgment, don’t point fingers. Just state the facts with specificity, and let the reader draw their own conclusions. It’s more powerful and more effective that way, and you don’t insult anybody’s intelligence.

So, that’s what I tried to do with Nancy. And some of it’s flat out comical — I read all these passages to her, and I asked, “Are you okay with that?” In my book, there’s that situation with the police. Nancy said, “I gave him a piece of my mind…” And I went, “Can I include that?” She goes, “Yeah, you better include it!”

In terms of divorce and any interpersonal conflict, it is the objective of recovery that we have some sort of serenity in our lives The serenity prayer is, “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change (i. e. other people), the courage to change the things I can (that is me), and the wisdom to know the difference. Amen.” It’s a prayer that basically says, “Show me how to accept them and change me.” And acceptance is not approval. I’m never going to change my ex-wife. I’m never going to change my old man. I have to change myself. When you change your own behavior, everything around you starts to change. And that’s really what it came down to with my dad. I can’t take on Leonard Nimoy. There’s just no way. He’s too powerful, because was always a tough kid from the streets of Boston. There was nothing that was going to stop Leonard Nimoy from his success. And he’s loved by millions of people all over the world. My dad changed when I just said, “I accept you. And I’m going to make an amends for my part that you think is why our relationship is so screwed up. I’m going to just make the amends and leave it at that.”

IK: You took responsibility and made amends for your part of it, and your father followed suit in the ways he could. And I thought it was beautiful — bringing you to Shabbat services to give you a moment for yourself during a very difficult time, and being more involved with your family towards the later years. I thought it was a wonderful way to discuss how we all play our own part in every relationship.

AN: It’s not easy, because I’m strong willed too and I just want to prove that I’m right. But I was told, number one, to go make the amends to my dad. We call it “fake it till you make it.” Just take the action and the feeling will come. We have a choice, to be right or happy, but sometimes you just can’t have both. I know I was right about my dad. I know what happened with me and him. In the end, it didn’t matter.

IK: I think it also goes back to what you were saying before — the character of Spock gave all of himself for the betterment of the crew. You were saying that so much of Spock’s character is like your father’s own life, but I think you also really embody those same values. You did it for the betterment of your own life [and that of your loved ones]. I didn’t know that much about recovery before reading your book, and I think I gained a lot of insight about it, and again, it’s not something that everyone talks about. So it’s interesting to see how it affected each area of your life and helped you learn how you wanted to go about interacting with others.

Spock is a character deeply influenced by your father’s Jewishness, as seen in the Vulcan salute, as well as the general idea of Spock being considered “different.” You write about this in your book, but I am curious to hear more about some other ways Jewishness played a part in your relationship with your father or your perception of him.

AN: My parents were raised by Orthodox parents, but they were not as observant. I think it’s a little bit of a retaliation and rebellion on their part, to change the way they wanted to go through the world. There was just an unspoken connection to Judaism and Jewish tradition. My dad loved the fact that he knew Yiddish, and he was reading all these Isaac Bashevis Singer books. He was very steeped in Jewish tradition. I spent a lot of time in shul with him and I liked that. It was one of the ways I was able to connect to my dad. He did take me to Beit T’Shuvah, a congregation but also a residential addiction treatment center, and that did change my life because I’m there every Friday night now. I mean, I’m a board member there. That’s a part of my recovery; it’s a big part of my community. So, in that way, he gave me that gift.

I want to live in the moment. The now. This is a part of the legacy of Leonard that you mentioned in your initial questions, about understanding my father and his legacy through the process of writing the book. The fact of the matter is, legacy is the impact of a person’s life. The thing that’s really interesting for me, and it dovetails again with Torah and what we were just talking about: the conversation about legacy came up over dinner at my dad’s house. My stepmother asked me, “Do you ever think about what your legacy will be and what is the impact of your life?” And I said, “Well, quite honestly, I’m just struggling with living in the moment.” And my father said, “Good answer.”

Because Leonard was all about being in the moment, being on set, being in the character. What do I do next? Not resting on your laurels, constantly exploring, constantly pushing the envelope, and bringing our tradition with us. This is why the lessons of Torah infuses the moment for me. Leonard was very much about this; every great artist, I believe, is this way about living in the moment. And that is the true legacy of what my dad stood for — to me — as an artist.

Now, the other aspect is family. My father talked about the fact that early on in his life, all he cared about was career and his work. That was always the priority to him. Second, to nothing, not even the family. Later in life, it switched for him. And he acknowledged that the most important thing to him in terms of his legacy really is his dedication to family. That is squarely in our Jewish tradition. Like with my ex-wife: I had Passover with her and both of our extended families, all under the same tent together.

And that’s my father’s legacy on a personal level. He never set out to make this pop culture icon, it was never his intention. His intention was to give everything he could in the moment to that character, to bring him to life, to be specific about how he played that character. And in that specificity, it happened to resonate — his legacy is that the world still knows, and will always know, Spock.

IK: Is there any significant memory or moment that didn’t make it into the book but that has stuck with you?

AN: There are two things that came to mind immediately. When I was very young and they were making Star Trek, I was on the set, and I had my father sign autographs. In retrospect, I can see in my mind’s eye how powerful the moment was. He signed these two things and he said to me in typical fashion, “That’s enough. No more pictures.” And then he went all introspective into thinking about the scene and the work he was going to do that day, all into Spock. I was there with Spock. I was with him! To be there with this character who is my father, but is not my father, in full makeup and full wardrobe. And I’m just a ten year old boy on a soundstage. It’s just an amazingly powerful moment for me, knowing now how much that character has resonated with the world. So that, in memory, is a very powerful thing — again, I’m not changing the past, but I am recreating it, infusing my memory with more meaning.

The second thing that came to mind was something that happened about a year before he died. I happened to be watching this two-parter episode of Star Trek entitled “The Menagerie,” it’s a phenomenal episode and my dad is just incredible in it. And I went to his house for dinner and I said, “Dad, I just watched ‘The Menagerie’ and you were outstanding in that show.” And he said to me, “When we got to that episode, I was really on my game.” These moments are important because these are the ways I connected to my dad. I didn’t have the visceral lovey-dovey connection that I have with my own kids. And when I had my kids, it became more apparent to me of what I had missed with my own father. But the things that I did have, I cherish now, and I really hold on to very tightly. And that’s what I’m sharing with you.

[We then chatted more about book and film recommendations for a while. But, of course, the Zoom timer was running out, and we had to end the interview.]

Isadora Kianovsky (she/her) is the Membership & Engagement Associate at Jewish Book Council. She graduated from Smith College in 2023 with a B.A. in Jewish Studies and a minor in History. Prior to working at JBC, she focused on Gender and Sexuality Studies through a Jewish lens with internships at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and the Jewish Women’s Archive. Isadora has also studied abroad a few times, traveling to Spain, Israel, Poland, and Lithuania to study Jewish history, literature, and a bit of Yiddish language.