Who can laugh at a time like this?

It’s a question I ask myself multiple times every day, particularly in these nerve-wracking times. It’s an especially awkward one, considering that my profession is “comedy writer.”

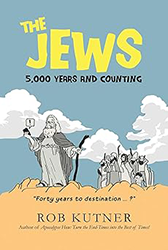

This question froze me in place as I sat before my keyboard on October 7, 2023. I was in the middle of writing The Jews: 5,000 Years and Counting, my new book, a comedic look at the entire history of the Jewish people. Working for late-night hosts like Jon Stewart and Conan O’Brien, I was conditioned to write hundreds of words a day but now it took me nearly a month to be able to come up with one sentence.

And yet, it is hardly the first time in our history when we Jews — especially the tummlers, badchanim, and various other shticksters — have faced this question.

Their response, just like mine, ultimately became: what other choice do we have?

And it’s a question that surfaces in a literal and legal sense this week, as we celebrate Purim — a holiday in which we are commanded to feast and party, centered in a month in which we are commanded to turn grief to joy.

Yeah, so what? I can hear the skeptics crowing. We’re commanded to do a lot of things. Many of us don’t. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to the new H&H popup to eat a bacon-egg-cheese bagel sandwich.

Well, to them I would respond that deliberately cultivating Jewish joy — quite truly laughing in the face of despair — is vital to our people’s making it through whatever this is. Even if it’s just to the next this to come along. And let’s face it, there’s going to be one. Then another.

But as Rabbi Tova Leibovic-Douglas writes: “This practice – choosing joy despite difficult circumstances – is a core part of why our people have not only survived but, in many ways, thrived through the generations.”

I remind you that Purim is a holiday that arose from a situation in which the Jews were framed as a threat to society and it was determined that they needed to be eradicated. This all took place in ancient Persia, modern-day Iran, where the leadership wanted to wipe Israel(lites) off the map. Sound familiar?

And yet, it gave rise to the famously most uproarious and comedy-driven annual tradition on the Jewish calendar. How did that come to be?

At the end of Megillat Esther, the ascendant eponymous queen ordained that Jews commemorate our near-miss from annihilation through a few concrete mitzvot, which we still observe: helping the needy, supporting our communal centers, and sending gifts to friends and loved ones. And, of course, retelling the story behind the holiday.

But that’s just the thing. How do we bring this old story alive, in that dramatic and immersive way that we’ve mastered for Passover, Sukkot, and Hanukkah? Queen Esther’s decrees, and subsequent Rabbinic law, didn’t take up this pedagogical challenge, outside of rules on how/when/where to read the Megillah, and that we should get really drunk (which is not necessarily a guarantee of happiness!).

So that’s where Jews historically stepped up with the Purim spiel. We may think of these loud, outrageous, irreverent restagings of the story of Esther, Mordechai, and Haman (I’ll pause) as a relatively recent “Hey kids, temple can be fun too!” concession to modernity. In fact, Purim spiels date back over 500 years, a tradition kept during some of the most harrowing chapters of Jewish history.

Finding a way to laugh even amidst the tears is how we stay Jews.

The earliest documented “Purim spoof” actually dates back to fourteenth century Italy, when Kalonymos ben Kalonymos, a rabbi (and apparently, nepo baby) wrote a Talmudic parody called Masekhet Purim. In the sixteenth century, the Venetian Jews — sequestered in the first example of a ghetto, kept from leaving by armed guards, and severely restricted in life and livelihood — penned a comedic poem recounting the story of Esther. How could they laugh at such a time? The Jewish answer is: how could they not?

Other parodies of Jewish texts, from the liturgy to the Haggadah, began to appear in the Venetian ghetto, united by the theme of drunkenness and a recurring mock-prophet character named Bakbuk (Hebrew for bottle). Already there was an expansion from merely “humorously recounting a sacred story” into “opening the floodgates of addressing tragedy through laughter.”

Soon after, Italian Jews began dramatizing the story by burning, and sometimes attacking on horseback, effigies of Haman, accompanied by trumpet blasts. Not exactly hilarious, but also not exactly the Mourner’s Kaddish either.

In the seventeenth century, the tradition of the Purim spiel— sometimes a lavish stage production with wardrobe and original music — began to take off across Europe, even as numerous unspeakable things were being done to Jews. Even as they were trapped, geographically and otherwise, in misery.

Perhaps the most arresting example, though, of a Purim spiel staged in the face of horror was the one put on by the Bobover sect of Hasidic Jews in 1948. Still reeling from near-decimation by the Nazis, this sect cobbled together memories of the spiels they used to put on in Bobowa, Poland, and reignited the tradition — one that continues to this day.

As you may have gleaned by now, I personally have a passion for Purim spiels. When I lived in New York City, I used to recruit professional writers and actors to mount an annual show I called “The Shushan Channel,” which played in New York City Jewish venues for eight years. Since moving to Los Angeles, I’ve been helping make elaborate ones at my own shul for the past decade and a half. Yes, even through those times. Especially.

And that’s the spirit in which I wrote my funny book about Jewish history. Now. You heard me.

Because, as absolutely horrifying as the moment we seem stuck in, looking at the bigger picture of all of Jewish history can be existentially therapeutic. It reminds us that we’ve been through different horrors, many times, and we’ve always made it through.

Looking at all of this, living through this, with an eye towards irreverence, subversiveness, and digging hard within ourselves to unleash joy — that’s how we’ve made it. Taking the long view of Jewish history is critical to the continuation of Jewish history. And finding a way to laugh even amidst the tears is how we stay Jews.

The Jews: 5,000 Years and Counting by Rob Kutner

Rob Kutner is an Emmy-winning comedy writer and bestselling author who has written for The Daily Show, Conan Marvel, and too many Purim spiels to count.