Memorial to the Martyrs of the Deportation, Paris. Photo: Daniel Fryer

The great theologian Karl Barth once said, “It may be that when the angels go about their task of praising God, they play only Bach. I am sure, however, that when they are together en famille, they play Mozart and that then too our dear Lord listens with special pleasure.” What a lovely and apt image for a composer christened Theophilus — a name in which both God and love are inseparable — better known, of course, as Amadeus.

As program director and announcer for Miami’s late, lamented classical radio station, WTMI-FM, I especially enjoyed choosing music for the month of January — the month in which Mozart was born — starting out the year with Mozart’s first piano concerto, both the day and the music filled with promise. Every succeeding day in January, I played another piano concerto on the air. Finally, I would announce his Twenty-Seventh Piano Concerto on January 27, Mozart’s birthday.

It’s his last work in the form and a masterpiece in its own way. The serene middle movement is filled with a wintry beauty, reminiscent of the line from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73: “Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.” Perhaps the elegiac tone resonated every time I heard it on the composer’s birthday only because I knew that by December of the year he completed it, Mozart would be dead.

Long before the music died on WTMI, I had moved on, leaving behind my radio voice to find a writing voice. When I was researching my novel, I learned of another event that had taken place on January 27, almost two centuries after Mozart was born: the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945. Much of my book is set against the backdrop of Notre Dame, but behind the cathedral’s soaring towers is a memorial that sinks into the ground. At the Deportation Memorial, a bronze circle is chiseled with the words: “They went to the end of the earth and they did not return” — a reminder of the dark shadows that underpin the City of Light.

As I delved into the dark years when Paris was under Nazi occupation and Jews were being rounded up, it was a shock to realize that Mozart’s exuberant Thirty-Sixth Symphony, the Linz symphony, was written for a visit to the city where much later his fellow Austrian, Adolf Hitler, would spend his formative years. When the world subsequently learned of the horrors of the concentration camps and came face-to-face with the unthinkable number — six million — it seemed that art, music, and language must all be rendered mute. What words, images or sounds could be equal to the task of confronting the scale of the Shoah?

What words, images or sounds could be equal to the task of confronting the scale of the Shoah?

Yet art, music, and language were also acts of resistance for those swept up in the Shoah. The concentration camp at Theresienstadt (the German name for the Czech town of Terezín) was where the musical luminaries of Prague were herded, as Joža Karas writes in his book, Music in Terezín 1941 – 1945. They performed, they conducted, and they composed. Survivors credited music with saving their lives, which was literally true in cases where their skills kept them from being sent “east,” a euphemism for certain death in one of the extermination camps.

At one of the performances at Theresienstadt, Rafael Schächter conducted Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem. The Catholic mass for the dead was a controversial choice for those held in a Jewish concentration camp and even more so when presented at a gala performance hosted by Adolf Eichmann for the Red Cross. But it was also an act of resistance; as Karas points out, the Jews were openly condemning the Nazis in the words of the Dies Irae, which they sang:

Lo! the book, exactly worded,

Wherein all hath been recorded,

Thence shall judgment be awarded.

When the Judge his seat attaineth,

And each hidden deed arraigneth,

Nothing unavenged remaineth.

Theresienstadt was a Potemkin camp, a show put up to deceive the Red Cross and the rest of the world about how Jews were really being treated. But in other camps, even where the prisoners knew they were facing certain death, they continued to write, draw, and compose. In a recent 60 Minutes segment, Italian pianist and composer Francesco Lotoro recounts how he has been gathering, completing, and performing all the music he can get his hands on from the concentration camps. To him, this is not just the music of the inmates, but also their “last testament.” Although many perished, their music lives on. It is a call to memory: never forget.

Although many perished, their music lives on. It is a call to memory: never forget.

But it seems we are in danger of forgetting. Grim echoes of the past are everywhere: Jewish graves defaced by swastikas in Alsace, deadly attacks on synagogues in the States, primary school children participating in a horrific Auschwitz-themed ballet in Poland. The words of writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi are chillingly pertinent: “It happened, therefore it can happen again … It can happen, and it can happen everywhere.”

This January 27, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, dignitaries from around the world will gather to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. I will watch the live broadcast of the ceremony. I will also think of Karl Barth, who defied Hitler and loved Mozart, as I listen to the Twenty-Seventh Piano Concerto by the composer ‘beloved of God.’ But in the ensuing silence, what will continue to reverberate in my mind are the words: Never again, never again, never again.

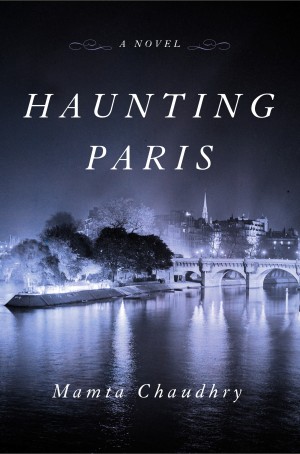

Mamta Chaudhry’s writing has been published in the Miami Review, The Telegraph, The Statesman, and Writer’s Digest. For many years she worked in television and classical radio at stations in Calcutta, Gainesville, Dallas, and Miami. She and her husband live in Coral Gables, Florida, and spend part of each year in India and France. Haunting Paris is Chaudhry’s first novel.