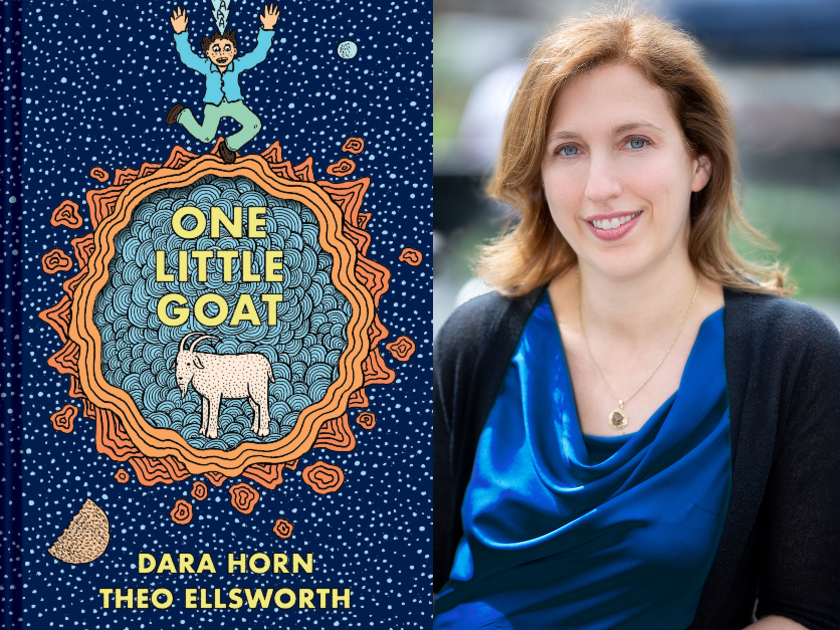

Emily Schneider spoke with acclaimed author Dara Horn about her new graphic novel, One Little Goat: A Passover Catastrophe. Illustrated by Theo Ellsworth, this fantastic tale begins when a child misplaces the afikoman, setting in motion a voyage through Jewish history and one family’s past.

Emily Schneider: Dara, I’m going to start by asking you what may be an obvious question. You have a very successful and acclaimed career as a novelist and a public intellectual writing about a range of subjects. What motivated you to write One Little Goat, a graphic novel of interest and concern to both children and adults?

Dara Horn: I actually first thought of this idea a number of years ago. I was on a road trip with my family in California, with my four children, and we stopped at a comic book shop. My kids are all into this kind of thing. And one book that they came home with was a very, very thick graphic novel by this cartoonist, Theo Ellsworth. They were fighting over this book throughout the whole trip! I borrowed this book from them, and I was just enchanted by the artwork. And at that point, an idea I’d had for a graphic novel sort of came roaring back to me. I could see how it could come to life, now that I saw an artist whose work I really appreciated. And I looked this artist up; I knew nothing about him. He’s a pretty acclaimed indie comics artist. Theo Ellsworth, lives in Montana. He’s probably not Jewish. This is a kind of deep in the weeds idea for someone who doesn’t know much about Passover. I cold-emailed him, said, “Hi, I love your work. I’m a writer. Here’s an idea. It’s a little hard to explain.” And he was totally game. But the deeper question that you’re asking is, why would I do this when I’m really writing for adults my whole career? This is an idea I’ve been thinking about since I was a child. I’ve always been fascinated by the seder and how it is much more similar to other seders than it is to other days of the year. When you’re at the seder table, it’s much more similar to being at a seder table ten years ago than it is to something that happened the week before. And it feels much more connected through time than space. This is something I’ve been fascinated by since I was a kid — the idea of Jewish life and texts being a portal to a past that we really shouldn’t have access to is something that I’ve written about in all of my books. All of my books are some version of this. This is simply the most direct version.

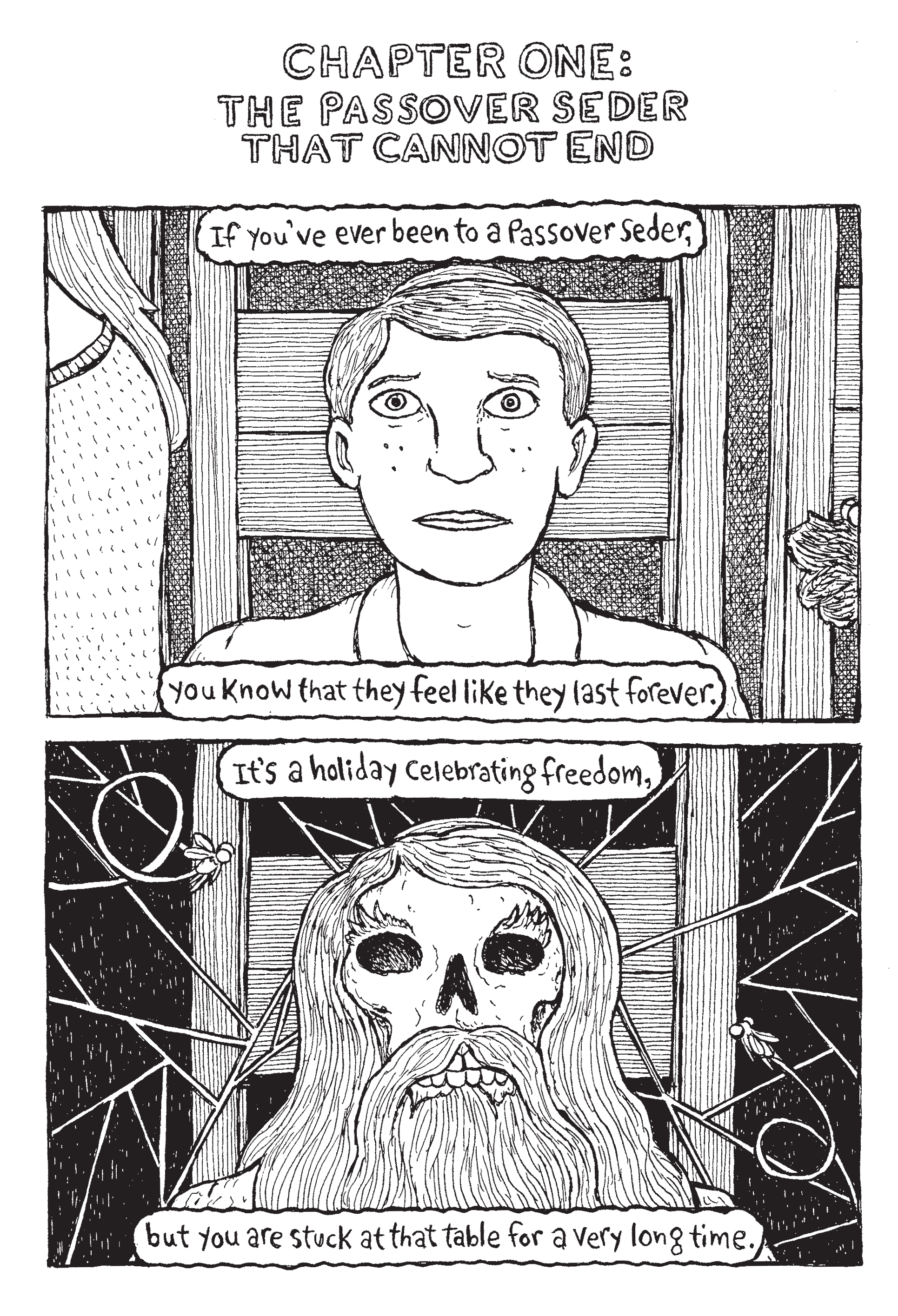

ES: You begin your journey into Pesach, the festival of freedom, by reconsidering a myth. This is a holiday Jews throughout the world are celebrating. It’s so imbued with meaning for everyone, across a broad range of religious observance. So it must be an unalloyed joy for children, right?

DH: Yes, and also because it’s a holiday that’s ostensibly supposed to be centering children.

ES: That is really at the center of your book. For many kids, it could be tedious, repetitive, a little bit opaque, even though, as you said, children have a starring role.

DH: Yes, this holiday’s celebrating freedom, but you are stuck at that table for a very long time. This is a dynamic that I’m very familiar with because my whole family’s life has been built to protect children from it. I’m the host of my family seder.

I’m one of four children, and, in the seder that I grew up in, my parents avoided this boredom by having us be very involved in a creative way. We would have to write songs and skits, acting out the different parts of the story. It was different every single year. We would work on this whole show that we would put on at different points in the seder. The story of Abraham smashing the idols would be Mesopotamian Idol, a parody of American Idol. It was always something based on whatever was trending in pop culture at that time.

Now, I also have four children. My parents have a total of fourteen grandchildren. So it’s a large seder I host, with a lot of young people. I had to make a decision. Either I can read every single page of the Haggadah, or I can have my children enjoy Pesach. That involves a ridiculous amount of creativity, and that’s what we’ve done. Our seder is very traditional in that we do read every page of the Haggadah. It’s very untraditional in that we use technology. We have all these different settings that you move through and you meet different characters in the Pesach story. In one room, the angel of death pops out of a closet and slays the Pharaoh’s son. In another room, we have a blue lasers and fog machine that fills the space with a blue fog, but only up to waist height. It creates this wave-like look on the surface. And as you walk through it, it parts in front of you. Everybody in our seder is personally experiencing coming out of Egypt. Some of these ideas I got from classical Jewish sources. Everybody’s very invested and the other most important part is the kids have roles in our Seder. And it’s become a competition every year of who can make it newer, more interesting, funnier. My daughter’s the wandering Aramean; she comes and she has a scroll that she wraps around the entire room that has the passage we all read out loud together. We have light-up Had Gadya animals that my husband made by soldering a bunch of LED lights together. So it’s like a Vegas seder!

Every year we make a movie out of these pieces and recreate the Pesach story. We divide up the story into the different family pods. This group of siblings is assigned to do the burning bush or some other piece of the tale. And then the final product is screened. No one knows what the other people have done, but everybody feels very invested in their part.

ES: The search for the afikoman, for a lot of families, is a brief scavenger hunt that ends the meal. How did you decide to make that the central motif of the story, a possibly endless journey into the past?

DH: This actually was sort of inspired by another seder that I went to growing up. For the second night, we would go to family friends that hosted this gigantic seder, with forty or fifty people. It was multi-generational, with everyone seated by age at this very long table. The old people were at one end and the kids were at the other end.

The people at the end of the table had survived the Warsaw Ghetto. They were singing a partisan song. Now I have a PhD. in Yiddish, but, at the time, I kept asking them to translate, and they wouldn’t. There was a middle section of the seder with people who were Soviet Refuseniks who had come over to the US 1979. They were using the seder as a part of their movement for Soviet Jewry. And then there were the kids on the end who were sort of just sitting around joking about The Simpsons. It was as though three very distinct seders were happening. The one part I really enjoyed and looked forward to at the seder in my house, was finding the afikoman which my dad had hidden. At this large seder, it was the opposite — the kids would hide it. This family’s house was much less organized than mine and there was a feeling of total chaos and there was always a point where someone didn’t remember where they had put the afikoman.

ES: You extended that experience. What if the afikoman actually disappeared and ended in time travel?

DH: Exactly. The reason that you give a prize to somebody to get the afikoman back is because you actually can’t end the ceremony without it.

ES: You pointed out that children are central to this celebration. At the seder, the four questions are performative and are an opportunity to give the parents an opportunity to kvell. The four sons, or children, are different. To me, that embodies one of the worst mistakes we could make as parents, which is to assign a personality to each child and compartmentalize them. Instead of simply refuting that, you have the oldest child come to an understanding of himself and why that is such a misleading way to look at families. How did you develop that idea?

DH: Yes, that’s the take away for the child who’s reading it, because children are looking for that sense of self. They’re in this identity formation part of their lives. As an adult, you look at the four children, and think, there’s a little bit of each of them in each of us. There’s moments in my day where I go through all four of these personalities. But as a child when you read about these four sons, you are not thinking that. Even when an adult tells you that, you’re thinking, “Yeah, but not really. My brother is the wicked son.” You have this sense of self-righteousness. I grew up in a family with four children, and now I have four children. Every time we got to this page, it always felt very personal. What I think about as a parent is, when you look at what you think of as your child’s worst quality, you are also looking at your child’s best quality.

ES: That’s true.

DH: Let’s say that your child gets really angry a lot. Is that the worst quality? Who else gets angry a lot? Moses. That guy has a major anger management problem. He sees the Egyptian taskmaster beating a Hebrew slave. He doesn’t write a letter to the editor about it. He kills the guy. He keeps getting angry throughout the Torah. He’s yelling at Pharaoh for the whole book of Exodus. He’s yelling at the Am Yisrael for the whole book of Deuteronomy. He’s supposed to talk to the rock. He hits the rock. He comes down from the mountain with the tablets. He sees the people worshiping idols, he smashes the tablets. He keeps lashing out. He wouldn’t be who he is, and he wouldn’t have the leadership that he had, if he didn’t do that. Because anger is an emotion that’s tied to our perception of injustice. Moses has an exquisite awareness of justice, and that’s the source of his leadership. We want children to get rid of a trait, minimize or outgrow it, but what I’m suggesting in the book is something a little different. Perhaps there is something about that trait that you want to dig into deeper. Like the “wicked” child. Isn’t he actually someone who sees when something isn’t working, in a way that you never would because you like to follow the rules? Or the “simple” one may be a person who’s so much kinder than you would ever be.

That’s what the “simple child” in the book is thinking about, not the substance of an idea, but how does this affect someone else’s feelings? The child who doesn’t know how to ask turns out to be the key to the whole story. Children are really also really worried about that, about living up to their reputation in the family.

ES: They are. Another part that they will also identify with in the story is the perspective that children have of the adults around them. They love and respect their parents and grandparents, but they also find them intensely frustrating. The grandfather who’s a beloved, yet irritating, old person. The great-grandmother is super-old, and also irritating, but she’s a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto.

DH: The only thing she ever says is, “You’re doing it wrong.”

ES: That’s right. The oldest child starts to think about his own family dynamics. Why is Dad so serious about Jewish holidays? Why does mom want to have so many children? Young readers are going to identify with his feelings of ambivalence.

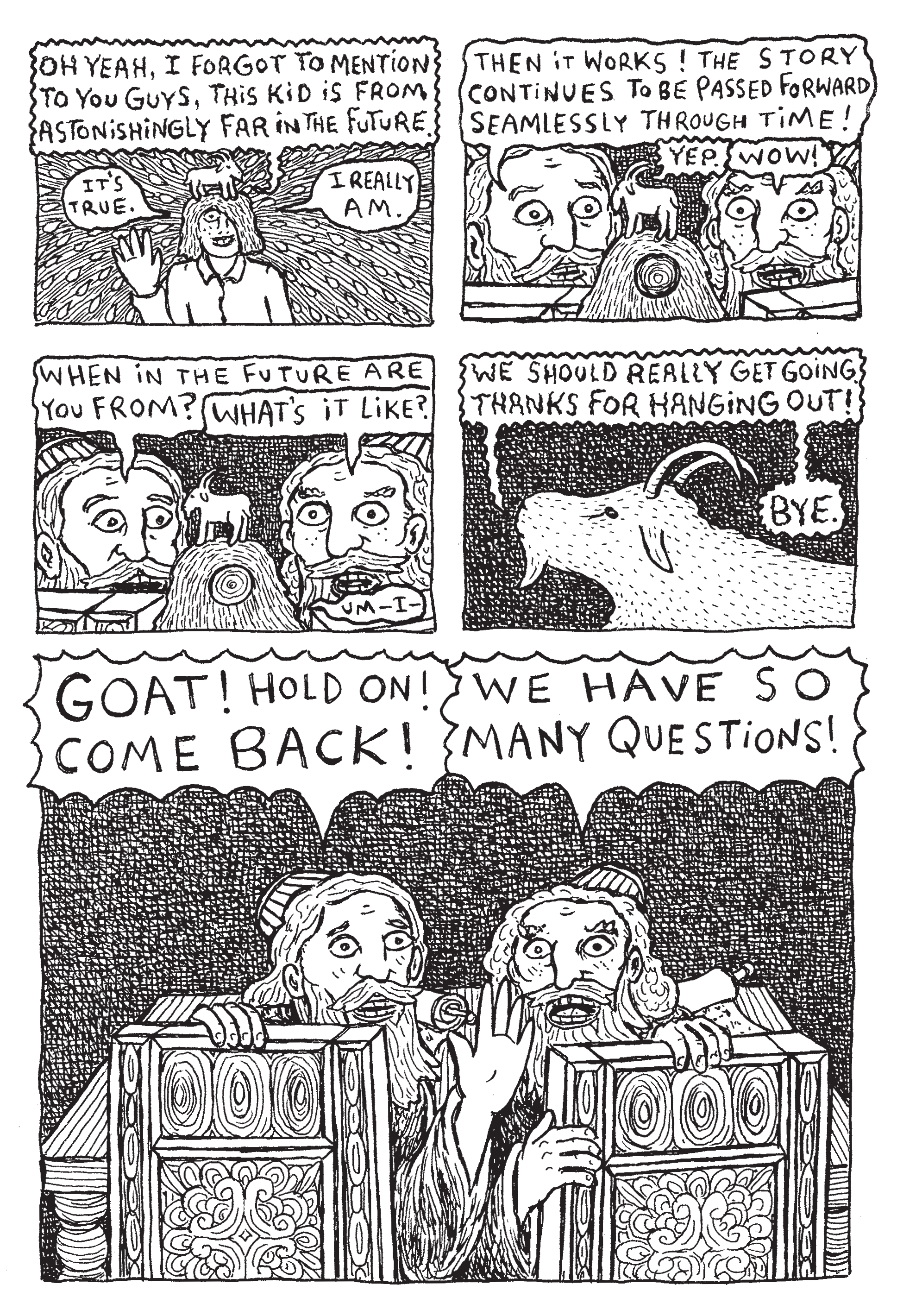

Art by Theo Ellsworth

DH: When he sees them in other contexts, as younger people, it suddenly all clicks into place. It’s driving him nuts that his dad’s so obsessed with holidays. Then he sees his father on Pesach in Minsk in 1982, when his mom smuggles a piece of matzah from a secret bakery. He sees his mother’s seder, and there’s no other kids at this seder table, and now she’s pregnant with her fifth kid. “Wow, that must’ve been really lonely for you.”

ES: Another part of the book has become countercultural in some ways today. Your journey through Jewish history seems like an implicit rebuke to the idea that’s become more prevalent, questioning the idea of Jewish peoplehood. Your use of the Hebrew term tel to describe the accumulation of archeological ruins of the seders, emphasizes that you’ve always thought of this holiday as timeless. How did you decide whom to include and where to go? (The time travel includes third century Babylonia, the Warsaw Ghetto, the eras of Gracia Nasi and Sigmund Freud.) How did you decide to assemble this picture of the Jewish people?

DH: This is a story about Am Yisrael, and what it means to be a part of Am Yisrael. There is also some diversity to what I’m representing. Freud’s seder is not a super observant one, it’s more like a Viennese dinner party than a traditional seder. There’s also some celebrations seen as names on the doors — Aden, in Yemen in 1949, Kibbutz Nahalal in 1958.

The seder is a reenactment of the Exodus from Egypt, but it’s also a reenactment of all the other seders that came before. That’s true in our own family’s lives. Each year, you’re reenacting previous seders, you’re reenacting what a previous generation did. But also within the seder structure itself, you’re reliving other seders. The Haggadah stops, to tell you this story about these rabbis in Bnei Brak, about how their “boring” seder went on all night. Except that if you learn this history, you know that these were rabbis who ended up being executed by the Romans because they were involved in a revolt.

I wanted to capture some of the diversity of seder experiences, but also the ways in which this story resonates at different points in Jewish history, points where it becomes literal. It’s the idea of Vehi Sheamda, that in every generation people have risen up against the Jewish people and God has saved us from their hands. This is not a book that shies away from this much darker aspect of Jewish history. I connect those pieces, which I don’t think are often connected so explicitly. The goat says , “They’re plotting a revolt against Rome.” And that’s similar to the Warsaw Ghetto seder.

Doña Gracia Nasi is included because this woman’s a superhero. She rescued tens of thousands of Jews from the Spanish Inquisition, bringing them to safety in the Ottoman Empire. And that connects, obviously, to Sephardi experience.

But, ultimately, I don’t think it’s about being Sephardi or Ashkenazi. Each of these stories is in many ways the same story, and are all part of the Am Yisrael story. I wanted to include Rav and Shmuel, two sages of the Gemara, because they gave us these two ideas of what the seder means. There is a debate between Rav and Shmuel about the purpose of the story, and the way you tell the story itself. The Haggadah that we have today includes both versions of this story. Shmuel’s version is that this is a political story about freedom from tyranny. You begin in Egypt and you end at the Red Sea. Rav’s idea is that the whole point of Pesach is the message of spiritual liberation. Shmuel’s idea is that we used to serve Pharaoh, and now we serve God. Rav’s idea is, we used to serve idols and now we serve God. That debate is not even a debate because, of course, we’ve settled it. It’s both of these things. I wanted to bring a child into that conversation.

ES: There’s another countercultural element, against the trend towards universalizing the seder, as a festival of freedom. Without denying the importance of that aspect of Passover, you focus on the particulars of the Jewish experience.

DH: I heard an interview recently about the surge in antisemitism. This person said, “We grew up with these traditions, like Pesach, where you’re learning about in every generation people rise up to destroy us. I thought that that was just educating me. I didn’t realize it was preparing me.”

Unfortunately, Jewish children today do need that preparation. But it’s not only preparing for doom, it’s also readying you to draw meaning from this tradition into your own life. It’s part of the preparation of understanding what it means to live with a historical consciousness. One Little Goat is not a universal story of liberation. Pesach is that, but in this book, I’m giving Jewish children a portal to travel through, so that they have access to this story, and to these resources, because they will need them. When I say they will need this story, I don’t just mean because of rising antisemitism. They will need it for whoever they become and whatever circumstances they find themselves in. I’ve needed it.

I’m hoping to highlight how Jewish peoplehood is basically just a really big family.

Art by Theo Ellsworth

ES: You mentioned that Theo Ellsworth’s work was your entry point into the book. His work has underground comics elements and I think that one of the reasons why the pictures are so evocative is because they are irreverent.

DH: As you say, there is something grungy and subversive about his work. He’s very edgy and it makes you feel like you’re looking at something you shouldn’t be looking at.

ES: The wrinkles on the great-grandmother are terrifying.

DH: Completely terrifying. And also hilarious. But what initially drew me to his work was how incredibly intricate it was. The level of detail in it activated in me a memory of illustrated books that I loved as a child.

Ellsworth is able to visualize and make concrete abstract concepts in an amazing way.I had this idea of an underground world. There would be lots of doors, and the doors would be labeled. You would open the door and come into the seder. He turned that into an Alice in Wonderland idea, where sometimes your head is the size of the door, and you come in and there’s small people inside. Sometimes you open that door and you’re tiny. And sometimes that door is a normal door, or a hatch in the ceiling. I never would have thought of any of this. That came entirely from him. The whole imagery of the clouds, of how you fast-forward 100 years in the tunnel, was from him. Even the idea of knocking on the door and illustrating the knock, of having a drawing of the sound of knocking on a door, these are not things I would have thought of.

Or the way that he drew the portal. I wrote in the script, “She throws the afikoman through a hole in the universe.” I was very vague about it. But he used that as a recurring idea, a way to communicate back and forth between these worlds. Ellsworth’s pictures have a subversive element; there is horror. When you go back to the original seder scene in Egypt, I remember him telling me, “It’s all going to be crosshatched and shaded. Everything’s going to have a totally different darker tone.” If you look at the way he draws the people and the room in that final scene in Egypt, he creates fear in every person’s face. Even the way he drew the goat. He uses dry humor, but there’s an integrity and dignity to the goat that I just feel another more typical children’s illustrator might have made it more, “Here’s a happy, fun animal. Here’s your animal sidekick.” And it’s not that. Instead, there’s a quiet fatalism.

ES: Dara, I feel as if you’ve touched upon my last question, but I still have to ask you: As an American Jewish author and a parent, how is this seder night going to be different from all other seder nights?

DH: This is our second seder after October 7th. In the first seder after October 7th, I was in a state of total despair. I’ve been speaking out basically non-stop, and I’ve been pulled into a lot of front row seats in a lot of situations. For example, I was on an antisemitism advisory group to the president of Harvard University. I was a witness in Congress’s investigation of Harvard about this. And I was in a state of despair about this at the seder last year.

This year, I’ve made a decision. I very recently founded my own non-profit. (Hopefully by Pesach we’ll have a website.) It’s called Mosaic Persuasion, and the mission of this organization is to educate the broader American public about who Jews are, starting in school settings and working through various other channels. So far, we’ve done workshops for school principals and administrators. The programs are not just, “Combating antisemitism. Here’s ten reasons why Israel’s not an apartheid racist state.” It’s a totally different approach that comes from my experiences in speaking with audiences around the country. Speaking often with non-Jewish audiences, I found that in my conversations with people around the country, there’s just so much more ignorance than malice. There’s a lot of room to turn this around, and the fact that there’s a lot more ignorance than malice means there’s a lot of opportunity to activate people’s curiosity. This year’s seder versus last year’s, I am feeling a sense of empowerment. I have hope going forward. Rabbi Akiva says it in One Little Goat identifying the meaning of the Pesach story, “The whole point of this is hope.” This is the innovation of the Pesach story, it is a way of imparting hope to future generations.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.