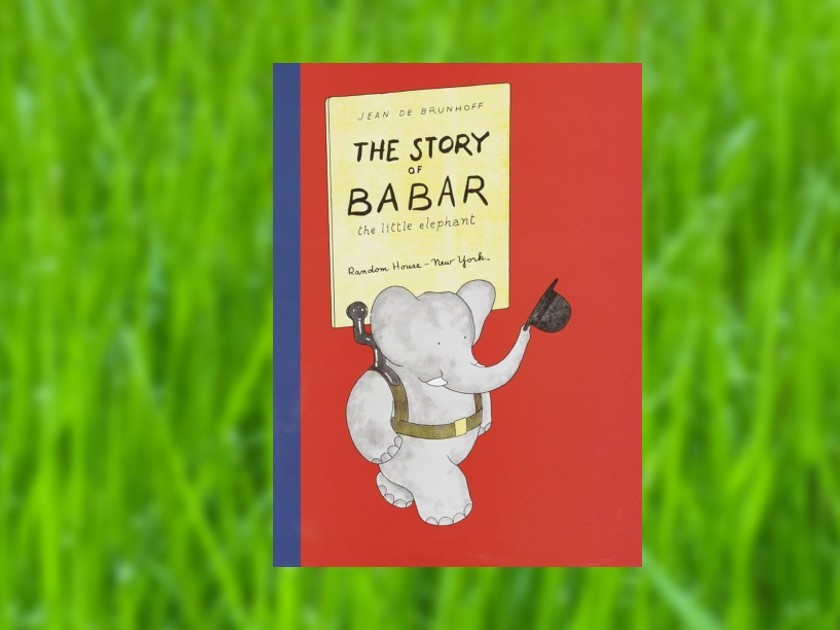

Laurent de Brunhoff passed away on March 22nd of 2024, at the age of ninety-eight. As an author and illustrator of children’s books, de Brunhoff has left behind a timeless and unique body of work. However, it is his series following the adventures of Babar the elephant that remain the most indelible of his artworks. Babar’s story was begun by Laurent de Brunhoff’s father, Jean, in 1931, and carried on by the younger de Brunhoff after his father’s death in 1937 at the age of thirty-seven. This fully realized world of carefully developed characters – pachyderms with a range of human qualities – has assured both his father’s legacy and his own.

By the twentieth century, the de Brunhoff family was not Jewish, and neither were their elephant creations. Yet, not surprisingly, given the pattern of Jewish assimilation in Europe, Jean de Brunhoff’s paternal grandfather was a Jew from the German territory of Baden who converted to Christianity. We can guess that Moritz von Haber, son of Solomon von Haber, was perhaps motivated to convert by a desire for social acceptance and professional success. This little-known fact about de Brunhoff’s genealogy might have been nothing more than a curiosity, except for the glimpse it offers into one of his later works of art. Meanwhile, the story of Babar begins with the titular character surviving the loss of his mother at the hands of a hunter, and ultimately marrying his cousin, Celeste, and becoming the patriarch of a close elephant family. He travels the world and establishes the equitable community of Celesteville (he even visits another planet in one story!). None of these adventures allude to a Jewish heritage or connection.

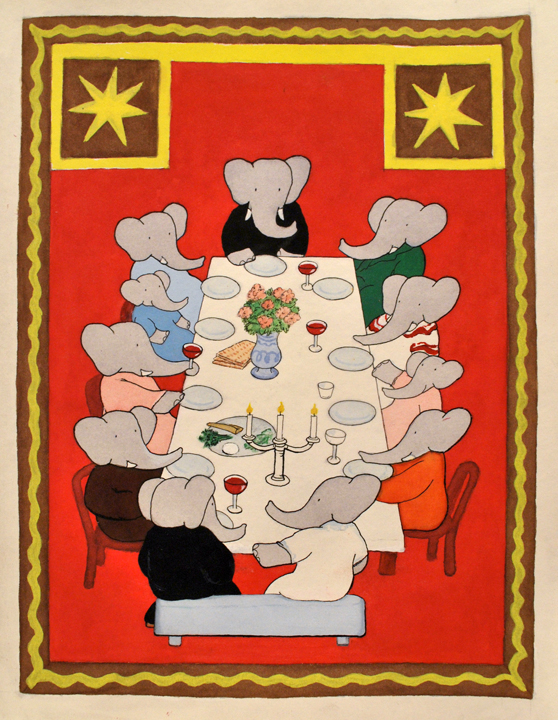

However, in the New York Public Library’s Dorot Jewish Division there is a unique compilation of Passover-themed art in the Rose Family Seder Books which offers new insight. Each year, the Rose family selected artists to contribute original works connected to Passover, creating an eclectic series of artists’ responses to the holiday’s meaning. In 2013, Laurent de Brunhoff interpreted the seder as a family gathering and religious ritual for Babar, Celeste, their children, and guests. They drink the four cups of wine, eat matzah, and recite the Four Questions with dramatic flair. In addition to the seder table and the children’s performance, there is the Rose’s annual list of guests’ signatures, enhanced with depictions of Babar and Celeste. What makes this seder night captured by de Brunhoff different from all others?

De Brunhoff captures the seder in motion. As at any seder, there are certain traditional elements included in the image. At the same time, de Brunhoff’s style unmistakably stamps the scene. Matzah, the seder plate, and glasses of wine indicate that the elephants are links in a long chain of tradition. Babar is identified by the suit described in the series as “a becoming shade of green.” Celeste and their children are present, as well as other adult elephant guests lending warmth and a sense of festivity to the occasion. These include anchoring figures of an elephant seated alone at one end of the table, with the visual contrast of a couple seated together at the other end. No one is wearing a kippah, perhaps an indication that this is a less traditionally observant family, or simply reflecting de Brunhoff’s choice of how to illustrate his familiar characters. The wine glasses which the elephants raise with their trunks are the larger bowled type specifically suited to red wine, and an elegant three-branched candelabra holds the holiday lights, details consistent with Babar’s Gallic style. The seder plate includes four of its five items and the matzah is uncovered.

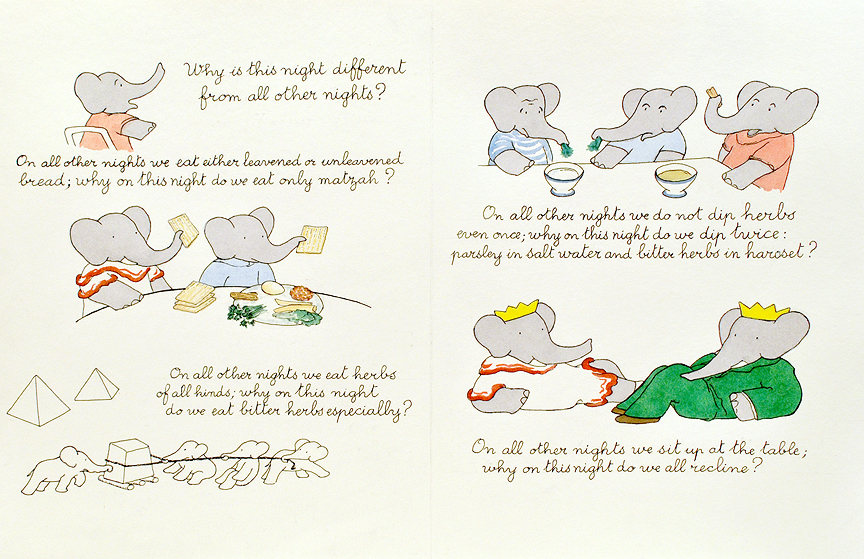

The next scene departs from the seder table, focusing on the Four Questions as delivered by Babar’s children. Shown separately from the rest of the guests, the painting accentuates the focus on children for this part of the night’s rituals. The children are not dressed identically as to how they appear in the seder scene, almost implying that what we see here is a rehearsal for the actual seder. Each question is accompanied by a caption in cursive, as were the original editions of the early Babar books. The children dip the herbs in salt water and charoset; the young elephant in a striped sailor shirt appears anxious, as he identifies with the implied tragedy. The children reenact the past, moving a heavy block of stone as enslaved Hebrews building for the Egyptians. Unlike the previous seder image, here the reclining Babar and Celeste are wearing their crowns. They are primarily parents, with the crowns signaling their benevolent authority as they prepare to answer their children’s questions.

The last component of de Brunhoff’s work is the list of guests who attended the Rose family seder. Babar and Celeste are facing the list, holding flowers and branches up towards words embellished with flowers, birds, and the figures of more elephants. These words are commands — “Extol, Reverence, Thank, Glorify” — selections from Hallel within the Haggadah.

As I sat before this glorious picture in the NYPL, I could not help but think of a related image in Babar the King, the third book in the series by de Brunhoff’s father, Jean. After a difficult day filled with near-tragedies, Babar has a bad dream. All his anxieties are personified as mythical creatures, but they are defeated by a flock of angelic elephants who trump the bad qualities with good ones, including: “Perseverance, Courage, Joy, Work, Patience.”

Whether or not Laurent de Brunhoff’s background played any role in the creation of Babar’s seder, he chose to embed the elephant king and family in a profoundly Jewish setting. Infused with all the brilliance of de Brunhoff’s seven-decade career, this seder night is indeed different and unique from all of Babar’s other nights.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.