Detail of stained glass with Magen David on door leading into sanctuary of Kehila Kedosha Janina.

Queens College Special Collections and Hellenic American Project

The Romaniotes, or Romaniote Jews, are the oldest Jewish community in Europe, dating back at least 2,300 years to the time of Alexander the Great. They are Hellenized, Greek-speaking Jews native to the eastern Mediterranean. They established communities in many Greek cities, such as Ioannina, where my parents were born. The first clear historical reference to the Romaniotes dates to the 1300s where they were mentioned in Byzantine golden bulls (official decrees). Additionally, archeological remains are evidence of earlier communities, such as the synagogues in the Agora of Athens and Delos, dating to the 2nd century BCE; mosaic inscriptions found in the synagogue on the island of Aegina are believed to have been constructed between 300 and 350 CE and used until the 600s CE. The Romaniotes lived in relative peace under Ottoman rule, and by the 1800s were involved in many trades, including owning small shops and family businesses.

On March 25, 1944, the nearly 1,960 Romaniote Jews in Ioannina — including my mother’s family — were deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz. Only 180 returned. Today, there are very few Romaniote synagogues in the world; there are a handful in Greece, one in Israel, and only one in the Western Hemisphere, the Kehila Kedosha Ioannina Synagogue and Museum in Manhattan.

The Romaniotes are distinct from the Sephardim who settled in Ottoman Greece after the 1492 expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Romaniotes traditions vary from those of the Sephardic Jews. For example, the Sephardim speak Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish language, while the Romaniotes use demotic Greek as their everyday language. Yevanic, or Judeo-Greek, was both spoken and written using the Hebrew alphabet. A few words that our parents taught us appear in my memoir, Flower of Vlora.

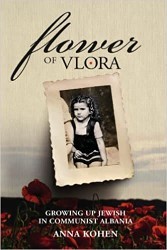

I decided to write my memoir, Flower of Vlora, for my grandkids; I didn’t know anything about my grandparents — especially from my mother’s side — except that they were sent to the concentration camps from Ioannina, Greece. The more I wrote, the more I realized that this story would have a larger audience.

In Ioannina, my paternal grandfather, Ilia, and his brother, Joseph, had a fabric dying business together. While the Jews of Ioannina earned their livings in many trades at that time, they worked primarily in the cloth industry. My aunt Nina was ready to get married to her future husband in Trikalla. According to Romaniote tradition, her family had to give her a dowry. My grandfather had no money and decided to take a loan out against the business. However, he could not repay the loan and the two brothers were forced to declare bankruptcy in 1938.

Many of the Romaniote Jews in Albania were hidden during the Nazi occupation of the country, and a number of Jews from the surrounding countries also found refuge in Albania.

My grandfather was a specialist in dying fabrics and was offered an opportunity by a Romaniote friend, also from Ioannina, in Vlora, Albania. He accepted the offer, moving his family to Albania, and ultimately helped his friend to save fabrics imported from England after a flood in the store. Joseph and his family went to Eretz Israel, today Israel.

My grandparents and my father, a young man at the time, met a small community of Romaniotes in Albania and decided to stay in Vlora. My father eventually returned to Ioannina, married my mother, and brought her to Vlora in 1942. Many of the Romaniote Jews in Albania were hidden during the Nazi occupation of the country, and a number of Jews from the surrounding countries also found refuge in Albania.

After the war, my parents came out from hiding in Trevllazer, where a Muslim family sheltered them from the Nazis. They could not go back to Greece, even though they were Greek citizens. We had great Romaniote friends in Vlora, most of whom had settled there before 1900. During the interminable period of Communist rule, the small group of Romaniotes kept the family traditions and practiced their religion secretly despite the watchful eyes of the Sigurimi, the police. There was no way for the family to leave the country, as Albania was under the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. They gave up the idea of escaping at that time and went on with their lives in Vlora. As years passed, the idea came up again more seriously as we kids were older; we had to orchestrate a scheme to leave.

My goal in writing the Flower of Vlora was to teach my children and grandchildren about their ancestors and their rich heritage. My hope is that they appreciate and are as proud as I am to be a Romaniote Jew.

Dr. Anna Kohen was born in Vlora, Albania, and left in 1966 with seven of her family members and moved to Greece where she completed Dental School and earned a dental degree. In 1991, and with the help of several Jewish organisations, she brought 37 of her Albanian relatives to the United States. That same year she was invited to Albania to celebrate the founding of the Albanian-Israeli society and was appointed Honorary Member. In 2004, the President of the Albanian Republic awarded her the medal for special Civil Merits for Valuable contributions in helping Albanians during the Kosovar humanitarian crisis. Dr. Kohen has served the Albanian community for over 30 years as President of the Albania American Women’s Organization.