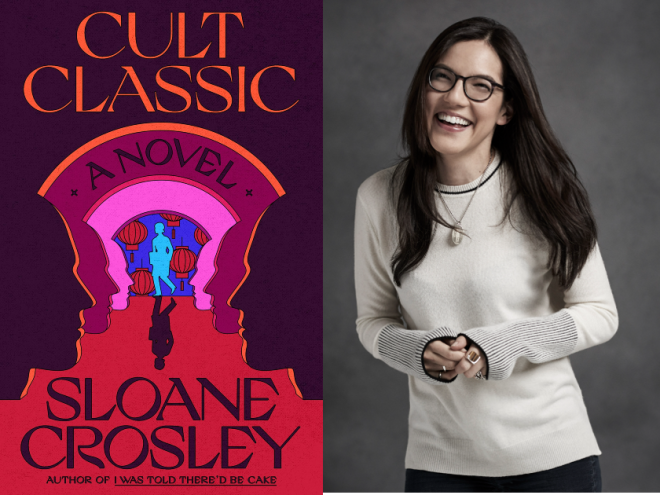

Author photograph by Petra Collins; design by Katherine Messenger

Wild, profound, and utterly unique, Melissa Broder’s second novel, Milk Fed, introduces us to Rachel: a woman in her mid-twenties with a judgmental mother, a soulless job at a Los Angeles talent agency, and a fixation on monitoring her calorie intake and remaining thin. At her therapist’s behest, Rachel makes a bulky clay figure to represent her worst fears for her body. The next day, the figure seems to come to life in the form of Miriam, a “zaftig” Orthodox woman who has started to work at Rachel’s favorite frozen yogurt shop. Instead of being repulsed, Rachel feels unexpectedly … lustful. In conversation with JBC editorial director Becca Kantor, Broder discusses the impossibility of separating the spiritual and the physical, the true meaning of perfection, and how she uses a “candy coating of humor” to reveal her deepest vulnerabilities.

Becca Kantor: Let’s start with the title. “Milk fed” seems to sum up so much about Rachel’s longings for different types of nourishment.

Melissa Broder: Milk Fed is really a story of appetite: there’s physical hunger, sexual desire, spiritual longing, and familial yearning. And it’s a look at the ways that we as humans — particularly as women — attempt to control and compartmentalize these interdependent instincts. “Milk fed” refers to physical hunger. It refers to maternal love. It also alludes to milk and honey — Rachel’s questions about her relationship, as an American Jew, to Israel.

BK: You weave the golem myth into your exploration of all of those desires through Rachel’s clay sculpture. What does this reveal about the interplay of all of Rachel’s fantasies and reality?

MB: For each of us, reality is malleable. After I wrote my novel The Pisces, people would often ask me if Theo, the merman character, was real. And I always said, Well, how real is anyone that we are ever in love with? How much is our perception of them, and how much is who they are? I often think that who we love is just as much a reflection of us as it is of the actual person. In some ways, any beloved can be a golem of sorts because there’s a layer that we create. That’s not to say that our beloved isn’t a real, functioning person in the world. But there are always those elements of projection.

BK: I was struck by how similar many of Rachel’s childhood experiences are to those you describe in your collection of personal essays, So Sad Today. In that book, you also mention fantasies that become realities for Rachel. In Milk Fed, we learn that a golem can be “a metaphor for that which is sought in the life of its creator.” Is your writing also a way of exploring different possibilities in or alternate versions of your own life?

MB: Rachel is not me. However, I am her creator. And I think, like with any mother and daughter, Rachel is going to have a lot of my attributes via nurture. She’s also going to have a lot of my attributes via DNA — simply the fact that she was born from me. I don’t see her as an avatar as much as a daughter. Or maybe like a clipping taken from a tree that has grown into its own tree.

BK: That mother-daughter dynamic is a central theme in Milk Fed. How did your own experiences inform Rachel’s relationship with her mother?

MB: Our parents are our first gods, and this may be particularly true of mothers. Milk Fed is very much a book that questions certitude: What are we being fed? Who has fed it to us? What were they fed — psychologically, culturally, and spiritually? Like Rachel, I have had moments when I looked at my thoughts and beliefs, and was stunned to discover that they weren’t monolithic truths — they were beliefs. I have had to ask myself: Are these even mine? How would I begin to dismantle them? Do I even want to dismantle them? What’s on the other side? The answers tend to fluctuate, but the questions are very good.

Our parents are our first gods, and this may be particularly true of mothers.

BK: Milk Fed shows how easily our perceptions of beauty can change. Could you talk about the fine line between what can be seen as repellent about the human body, and what is thought of as attractive?

MB: Miriam embodies a beauty that Rachel didn’t know she would find beautiful. Rachel cannot give that beauty to herself, but she can admire it in Miriam. It’s a case of what we fear most is what we desire most. Rachel also can’t give herself Miriam’s freedom of consumption, but in Miriam, she finds it fabulous. And even more fabulous because she is so afraid to give it to herself.

BK: Speaking of appearances, Rachel thinks of Los Angeles as only surface deep, a “Hollywood bullshit factory.” But for Miriam’s mother, LA is the city where she could be her most authentic self — where she could start her own business without being judged by the ultra-Orthodox community. Do you see your book as a commentary on LA? If so, what is that commentary?

MB: Los Angeles does have roots in the entertainment industry, and there is a lot invested here in the fake. However, I don’t know that in the twenty-first century, LA is that much more fake than any other place. The first time I moved to California — in my early twenties — I definitely had the California dream of, I’m going to go there and I’m going to learn to be chill and I will become a different person. And what I learned, of course, is that we take ourselves with us.

Rachel also brings herself to LA. She was already quite focused on her appearance before she came here. That said, for readers who don’t have the issues that Rachel has with body dysmorphia, LA serves as a good place to externalize that conflict. So much about appearances is monetized and is associated with the performative in LA simply by the nature of the industries that thrive here.

Miriam’s mother, Mrs. Schwebel, does liberate herself from some elements of her religious background, but there are others she doesn’t leave behind. She doesn’t even know why a person would want to free themself from certain prejudices, certain ideas. I think freedom often comes in different areas. At first Rachel perceives Miriam as very free, because Miriam is free in ways that Rachel isn’t. However, as Rachel gets to know Miriam she discovers that Miriam has her own limitations.

BK: Maybe most fundamentally, Rachel comes to realize that Mrs. Schwebel would never accept the idea of Miriam being in a relationship with another woman. How did you go about creating the Schwebels? Are they based on real people?

MB: The Schwebels were actually inspired by my experience of the Orthodox community. Growing up, I went to a Reform synagogue like Rachel. Before I was bat mitzvahed, we did an exchange program with Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn; we went to them, they didn’t come to us, because our houses weren’t kosher. I was very nervous about going, but I went. And I loved it. The food, the family, the humor. I was embraced.

Rachel’s impression of the Schwebels, especially upon first meeting them, mirrors that feeling of being welcomed. But then Rachel starts to question, What if I wasn’t Jewish? Would they still be so welcoming? She has moral and ethical questions, particularly regarding Israel, that she finds more difficult to cast aside. But the joy and the warmth that she experiences really reflect the time that I spent with the Orthodox community. While the Schwebels are all fictional, the cholent, the challah, the warmth, the laughter are not.

When I was with my host family in Brooklyn, I didn’t take into consideration the idea that I was welcomed because I was Jewish. And I wasn’t talking about my sexuality. I was certainly thinking about my sexuality at that age — in middle school, I was already romantically obsessed. But my host sister, who was a few years older than me, wasn’t even allowed to hold hands with a boy. She wasn’t dating. So those issues really weren’t coming into play.

I loved the innocence of it all. It was very Edenic for me, and it is only in retrospect that I think about the limitations of that world. And not even in the context of the Brooklyn family I stayed with — I’ve let that be just a beautiful experience.

BK: Rachel has a recurring fantasy of a shtetl that is also quite Edenic. How does that ideal serve as a foil to the world around her?

MB: Rachel is obviously aware of pogroms and the poverty and the restrictions on women that were very much a part of shtetl life. However, I think that Rachel’s shtetl fantasy is a desire to go inward — to get back to some sort of fundamental earthiness, and to feel rather than to perform. That desire gets sublimated into the shtetl as a symbol of realness and earthiness, a deep experiential feeling.

While the Schwebels are all fictional, the cholent, the challah, the warmth, the laughter are not.

LA is a very easy place to be a Jew in the twenty-first century. There aren’t any pogroms. There are flourishing Jewish communities. You’re not dealing with the snows of Russia or the cold of Poland. But at the same time, we can feel disconnected from our inner worlds and from one another, especially given the nature of all of our technology. So there can be a back-to-the-earth fantasy of a version of a place that might never have actually existed, but exists in our hearts.

BK: Especially because you first became known through your Twitter account So Sad Today, it’s interesting that Rachel’s relationship with Miriam seems to exist in a space where social media and modern technology are completely absent. And when modern technology does enter the story, it has an artificial or even toxic association for Rachel.

MB: I think the internet, like religion — like anything — contains potential for great beauty and for great disruption. Because Rachel is so disconnected from the physical experience of hunger, her body has become like a product for her. The relief of meeting Miriam and the Schwebels is very much about feeling and the internal. While the internet certainly can engender dopamine rushes and a lot of feelings, it is a very performative place. Part of what draws Rachel to the Schwebels and to Miriam is that their life seems grounded in the physical and the earth and food. Like when Rachel is at their Shabbat dinner table and she starts to think about the journey that the vegetables took to make it to the cholent. A potato growing in the ground — is that the opposite of the internet? I’m not sure, but to Rachel, it feels like the opposite.

BK: Rachel has a side gig as a stand-up comedian, and you do a fantastic job of integrating humor into her voice. Even though we only read a few lines from her sets, we fully believe in her ability just because the narration itself is so funny. In So Sad Today, you describe using humor as a mask to hide behind. Do you feel that applies to Rachel, too?

MB: A smile is very disarming. A smile can invite people in. But a smile can also be used as a shield. Like, I’m okay. Don’t ask questions. For Rachel, comedy serves multiple purposes. There’s the quest for validation, there’s the quest to be seen for who she really is, but at the same time, there’s still a defense. When you’re telling a joke or describing your pain in a funny way, you’re controlling the narrative.

I’ve always felt a desire to connect with people on a deep level. If I’m having a conversation and it doesn’t go to death, sex, and what’s really going on within fifteen minutes, I’m kind of like, Oh, this is exhausting. At the same time, I don’t have the confidence to just lay it all out there without giving it a bit of a candy coating because when you are being vulnerable, there is a fear of rejection. If I give you this candy coating, I can talk about these things, but you’re not going to feel compelled to try to solve them. This is about revealing rather than a cry for help. Rachel feels compelled to reveal herself, but at the same time, she doesn’t have the confidence to do so without the candy coating of humor.

I like to write in places where I’m not supposed to be writing — I don’t like writing at a desk.

BK: In addition to your novels and essay collection, you’ve written four collections of poetry. How does your background as a poet influence your narrative voice in fiction?

MB: One of the biggest challenges for me in writing fiction is the expansion of it. In poetry, everything is so concentrated. It took me a while to understand why I would say in two hundred pages what I could say in a two-page poem. In the end, it came down to the joy of spending time in a story. I love to read fiction, and in my novels I’m creating a longer experience for my readers — a world to get lost in for longer, the ability to spend more time away from their own reality. The way that my poetry background comes into my editorial process is that I read and edit my work rhythmically. There are certain things I’ve learned from writing poetry about rhythm, white space, and breath that I apply when I edit my novels.

BK: I feel like that emphasis on the spoken word relates to Rachel’s stand-up routine and narrative voice, too.

MB: Yes. I always dictate my first drafts of any work. That started as a functional thing. I like to write in places where I’m not supposed to be writing — I don’t like writing at a desk. When I lived in New York and I was writing poetry, I would write on the subway. And when I moved to LA, I began dictating in my car because I couldn’t type and drive. Milk Fed went through so many rounds of edits that there’s probably not all that much of the first draft left in there, but I think the conversational nature of my process definitely has an influence on the way my characters speak.

BK: In Milk Fed, Rachel uses Hebrew prayers almost as incantations. How does prayer function for you?

MB: I don’t pray to change the world; I pray to accept the world and to be able to stand within the universe’s will. In that way, I’m really praying to change myself. And then perhaps I can have some impact on the world. I don’t know if Rachel wills a golem into being — that’s up to the reader — but certainly Rachel wills personal transformation, which allows her to perceive the world in a different way. I like the idea that a miracle is not necessarily turning water into wine. It doesn’t have to be an actual burning bush. It can be a shift in our own perception.

A miracle is not necessarily turning water into wine. It doesn’t have to be an actual burning bush. It can be a shift in our own perception.

BK: What should readers ultimately take from Rachel’s spiritual journey?

MB: Every character in Milk Fed probably has more than one religion, but their denominations stray from the theological. If you look throughout the book, gods are made of familial approval, love, desire, the illusion of control. I think that all of us, even atheists, have gods. It’s just a question of what are you making your higher power.

When I was in my twenties like Rachel, I really believed that the answer was outside of me, and I was like a hungry ghost in search of it. I felt I had to figure it out with my head, and that any psychic-slash-astrologer-slash-new-age-priestess knew more than I did. Rachel is still searching doggedly for answers outside of herself.

Over the years, I’ve come to understand that everything I need is actually already within me. It’s just a question of being still enough to access it. Recently I was looking at all different definitions of perfection, and I found one that was “lacking nothing essential to the whole.” Like Rachel, my idea of perfection — whether that’s spiritual perfection, or a synthetic physical perfection — has often been based on an idea of lack and the necessity of striving for completion. But when I think about perfection as lacking nothing essential to the whole …Well, I don’t lack anything essential. I have all I need. So in a way, we are all already perfect.

Becca Kantor is the editorial director of Jewish Book Council and its annual print literary journal, Paper Brigade. She received a BA in English from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. Becca was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in Estonia writing and studying the country’s Jewish history. She lives in Brooklyn.