Plaza Murillo, La Paz, Bolivia between 1908 and 1919, Library of Congress

On an otherwise uneventful afternoon in 1975, John Gelernter was walking through the streets of his hometown of La Paz, Bolivia, when he saw a familiar face.

Terrifyingly familiar.

“That’s Klaus Barbie,” he told the French colleague walking with him.

Barbie, the former Gestapo chief known in Bolivia as Klaus Altmann, was accompanied by his bodyguard. They overheard Gelernter. As the two pairs of people drew closer, the bodyguard pulled out a gun and pressed it to Gelernter’s ribs. He kicked his ankles and threatened to take him to the police station.

“That is when Barbie told him to let me go,” Gelernter told me recently. “And speaking very softly in German, knowing exactly and surprisingly who I was, said something like this: ‘Herr Gelernter, there is space for everybody here (in Bolivia), so let me be.’”

Gelernter didn’t tempt fate. He had already lost too many family members to the Nazis.

Only when I moved to La Paz in 2012 did I learn that there were between 10,000 and 20,000 Jewish refugees in Bolivia during World War II, many of whom were musicians, artists, and performers. I wondered what it had been like to have lost home, country, family, and professional ambitions, and to end up somewhere so alien.

I met John Gelernter in the garden of the Spanish embassy not long after I arrived with my husband Tim, who was at that time the head of delegation for the EU in La Paz, and our young daughter.

While Gelernter is currently the Honorary Finnish Consul General in Bolivia, he worked most of his life as concertmaster and guest conductor of the Bolivian Symphony Orchestra. At the same time, he was managing director of Cibo, a large heavy equipment and machinery supplier. “I studied engineering,” he said. “My father encouraged me to be a musician but insisted I have another career.”

With green eyes and reddish-blond hair, he is still sometimes mistaken for a foreigner and complimented on his fluent Bolivian Spanish. But when John described his encounter with Barbie, I wondered what it must have been like to have family who escaped the Nazis in Europe only to encounter them in Bolivia. The more I learned about the lives of Jewish refugees in La Paz, the more I wanted the world to hear these stories.

I wondered what it must have been like to have family who escaped the Nazis in Europe only to encounter them in Bolivia.

While John was born in Bolivia, the sister he never knew was born in a part of Poland that was taken over by Ukrainian forces of the USSR in September 1939 and then occupied by Germans from June 1941 until July 1944. That part of Poland is now part of the Republic of Ukraine.

Gelernter’s mother Matylda came from Bolechów. She and her husband Chaim lived in Stanislawow until Chaim was conscripted into the Russian army. On November ninth, 1941, Matylda and her infant daughter moved in with her parents in Bolechów, where some 3,000 Jews made up about seventy-five percent of the city’s population.

They could not stay for long. In September 1942, Germans and Ukrainians carried out their second assault on the Jews of Bolechów, torturing and murdering nearly 700 children and close to 900 adults in the town square and on the streets. “They took the children by their legs and bashed their heads on the edge of the sidewalks, whilst they laughed and tried to kill them with one blow,” said Matylda in testimony dated August 1946 in Katowice, Poland, and now archived in Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem holocaust museum. “Others threw children from the height of the first floor.” Some 2,000 were taken to the Belzec death camps, while Matylda and her family hid in her parents’ house.

At the end of November 1942, Matylda and her two-year-old daughter Elunia found sanctuary in a shelter in a drugstore’s basement. Together, twenty-five or so Jews boarded the walls, bricked the windows, rigged up lighting, dug a toilet, stored potatoes and lard, and installed a stove. All work was done at night, to keep anyone from noticing.

Once they had all squeezed inside the shelter they had constructed, the door was bricked shut, save for a small gap.

“At first they didn’t want to let me into the shelter,” Matylda said. “They didn’t want so many people, besides, they were afraid that my child with its screaming or crying would give away the shelter.” Only after her brother interceded was she allowed inside.

They slept during the days, not daring to stir before eight in the evening. Each family was allowed to cook at specific times. Matylda could use the oven only at two in the morning. Occasionally, the pharmacist brought food or newspapers. Often, food ran out. The oven broke down. The toilet overflowed.

“One thing cheered us up,” said Matylda. “We had poison from [pharmacist] Feller. Everyone had one little bottle, just in case we would fall alive into the hands of the Ukrainian militia.” They feared the torture they would face at the hands of the Ukrainians, who ripped off the ears of their countrymen, broke their noses, poked out their teeth, or beat them to death.

Eventually Matylda and the others were pressured to leave the shelter, as friends and relatives who knew about them came under increasing threats.

Matylda weighed thirty-seven kilos when she left for the Jewish factory workers’ barracks, the only place Jews were allowed to live, in June 1943. Her hips and shoulders were covered with sores from sleeping on a bench. Her daughter had developed an eye infection and had gone blind in the dark of their shelter.

“I looked like a corpse,” Matylda said. “Green skin was hanging off me, my teeth were mostly gone too.”

She found work at a labor camp sawmill. Those Jews capable of it had to work, while the rest, including her parents, were sent to a ghetto in Stryj.

Matylda couldn’t take her daughter to work and thus had to leave Elunia with her parents. Her second day of work, she was too ill to get out of bed.

And her illness saved her. That day the Gestapo swept in, took all the workers to the cemetery, and shot them.

On June fifth, Matylda’s parents and her daughter were killed in the liquidation of the Stryj ghetto.

There was no time to grieve. Matylda crept from yard to yard, seeking a new hiding place as she wondered if her husband still survived. At last she, her brother, and his wife found refuge in a hole behind a Polish man’s stove on the outskirts of town. The homeowner became nervous and wanted them to leave, but Matylda said if he evicted them she would poison herself in his yard and everyone would know he had been sheltering Jews.

There was no time to grieve. Matylda crept from yard to yard, seeking a new hiding place as she wondered if her husband still survived.

On August 6, 1944, when the Russians arrived, they emerged from the hole. After a few days, they left the house to inspect the ruins of the town, destroyed by retreating Germans. The Russian army gave them canned goods and flour. Some fruit and vegetables remained in local gardens.

They lived there until October 1945. “At the end of October 1945, we all packed into a train and forever left Bolechów, which, after all, to us Jews was no more.”

Miraculously, Chaim escaped the Russian army at the end of the war and was reunited with his wife. They moved to Katowice for a couple years before traveling to Paris, France, where they spent six months waiting for visas to Bolivia. Not only was their hometown now a graveyard, but it was part of the USSR. They did not want to stay behind the Iron Curtain.

Matylda’s brother Jakob had found refuge in Bolivia in 1939. By 1938, Bolivia was one of only three countries still granting visas to Jews fleeing the Nazis.

In 1948, the same year they arrived in La Paz, Bolivia, John Gelernter was born.

His mother never spoke to him about her experiences, which he learned about only in adulthood.

Matylda’s brother Jakob had found refuge in Bolivia in 1939. By 1938, Bolivia was one of only three countries still granting visas to Jews fleeing the Nazis.

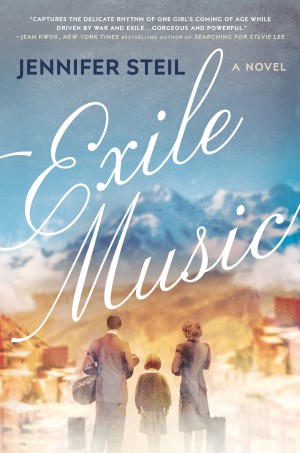

We lived in Bolivia for four years, until 2016. During that time and for several years after we moved back to Europe, I researched the book that became Exile Music, my new novel about a family of Viennese musicians who sought refuge in Bolivia. I interviewed survivors, read first-person accounts, traveled to Vienna and Genoa, visited synagogues, studied the history of the Vienna Philharmonic, listened to music of the era, visited archives, libraries, and museums, talked with Holocaust experts, and read about Klaus Barbie and the children of Izieu he ordered massacred.

All of this research sifted through me as I wrote, saturating me with the world of my characters. Many of John’s stories found their way into Exile Music. Like John, my characters are musicians. And they too have encounters with Nazis on the streets of their refuge.

Exile Music is a work of fiction, but it is my hope that the story I have crafted from research and imagination will allow readers a glimpse of a Jewish diaspora that has been too long overlooked. I owe it to John Gelernter and his family to keep them alive.

Jennifer Steil is the award-winning author of the novels Exile Music (Viking, May 5), The Ambassador’s Wife (Doubleday, 2015), and the memoir The Woman Who Fell From the Sky (Broadway Books, 2010) about her tenure as editor of a newspaper in Yemen. She currently lives between Uzbekistan and France.