After my mother died, I realized I needed to study Yiddish.

My mother didn’t actually speak Yiddish, but she peppered her conversation with Yiddish words. In the kitchen: “Hand me that shisl (bowl).” At the window on a rainy day: “A pliukhe (downpour)!” On the phone: “The woman’s a makhesheyfe (witch).”

When my mother died, I missed these words laden with heritage. (My father, though a great lover of all things Jewish, had been raised a Christian and couldn’t help.) Bereft of my mom, and wanting a way to maintain my connection to my Jewish forebears, I went looking for a beginners’ class in the language once heard in kitchens, lanes, marketplaces, and union halls on both sides of the Atlantic. Yiddish became my home within Jewish culture.

When I became a translator from Yiddish into English, I learned that Yiddish had a long history as a portable homeland for writers. In the words of the scholar Sebastian Schulman, Yiddish literature is “a truly transnational republic of letters, a body of texts that since its earliest days has been written, read, and sung across political boundaries.”

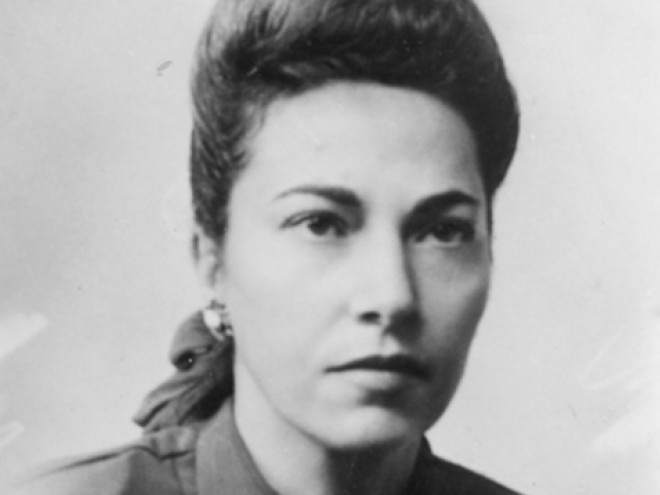

Sholem Aleichem was only one Yiddish writer who made a conscious choice to write in mame-loshn (mother tongue). Another was Yenta Mash (1922−2013), a little-known giant among Yiddish women writers whose work I’ve translated and collected in On the Landing: Stories by Yenta Mash (Northern Illinois University Press, 2018).

Mash is a master chronicler of exile. Her characters are always on their way to or from somewhere, always arriving or departing. Her work is urgently relevant today, as displaced people seek refuge across the globe. I put her alongside Jhumpa Lahiri, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and André Aciman for her keen insights into the experience of migration, assimilation, and resilience.

Gripping, honest, and somehow inspiring, no matter how grim the setting, Mash’s stories draw heavily on her own life — a life disrupted by repeated uprootings.

Born and raised in a small town, or shtetl, in the southeastern region of Europe once known as Bessarabia (today Moldova, east of Romania), Mash was deported to Siberia by the Soviets at the beginning of World War II. Though her exile saved her from the fate of Jews murdered by the Nazis, she suffered extreme hunger and privation during her seven years of hard labor. In 1948 she returned to Soviet Moldova, where she worked as a bookkeeper — and did not write — for three decades, before immigrating to Israel in the 1970s. There, finally, her words came pouring out, and received immediate acclaim. She published four volumes of short stories, appeared in Yiddish journals throughout the world, and received several literary prizes.

Those prizes were well deserved. Mash tells us much that we didn’t know about little-explored corners of Jewish experience in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and she does so in a richly elaborated literary style that is full of the friction of disparate cultures rubbing elbows.

As her characters struggle to adapt to new circumstances — whether in a harsh labor camp, in the postwar Soviet system, or in the not-always-friendly land of Israel — Mash portrays the most harrowing circumstances in meticulous detail. At the same time, though, she makes clear, as one critic wrote, that even “under hellish conditions, goodness and beauty can exist under the same roof. Often a kind of special illumination seems to shine forth out of that pitiless darkness.”

We see relationships forged, inner strength called upon, and a ceaseless wrestling with God. Mash’s characters keep the faith in their own way. They don’t stop believing, but neither do they let the Almighty off the hook for his many missteps.

When Mash arrived in Israel, her new land was hardly welcoming toward Yiddish, which was seen as an emblem of European oppression. Yet, like Sholem Aleichem and many others before her, Mash remained stubbornly loyal to her native tongue.

“Yiddish is my language,” she said. “In Yiddish I feel at home.”