Earlier this week Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub wrote about their discovery of the Elena Ferrante of Yiddish literature and her transgressive fiction stories, now translated into English as the collection Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories. Ellen and Yermiyahu will be guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all Week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

Two men are strolling together in the Borsht Belt when they come upon a flower by the side of the road.

“What’s the name of that?” one asks, pointing.

“How should I know?” replies the other. “What do you take me for, a milliner?”

The notion that the Yiddish language, and Jews themselves, are far removed from the natural world is well entrenched in the popular imagination. For Jews, the joke says, the only thing a flower is good for is trimming for a lady’s hat.

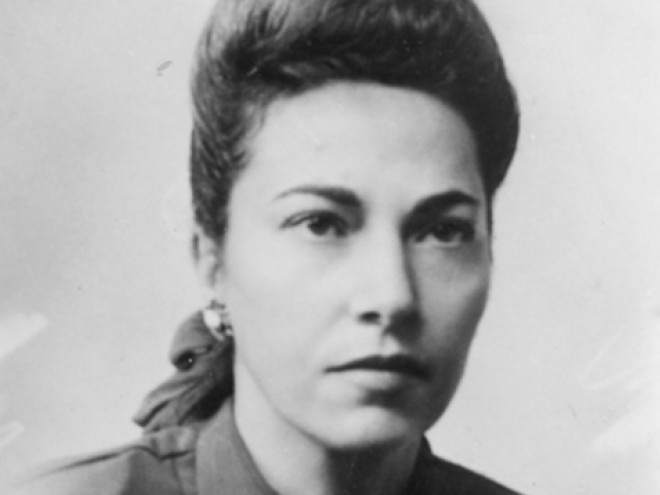

Yet in the fiction of Blume Lempel we translated and collected in Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories, nature plays a surprisingly significant role. Born in a small town in Eastern Europe in 1907, Lempel immigrated to Paris and then to New York, where she wrote in Yiddish into the 1990s. Her stories were acclaimed throughout the world of Yiddish letters.

In Lempel’s lyrical, jewel-like stories, the natural world operates as counterpoint, as driving force, as backdrop, and as protagonist. Sometimes the very hugeness of the natural world is invoked to put the life of the individual into perspective: one story opens with a vast world “encased in ice,” with “no marking of time,” where the “footsteps of eternity make no imprint in the void.” In another story, a woman flying to Reno for a divorce looks down into the “blue transparent void” that symbolizes her unknown future with its myriad choices; another woman lies under an apple tree on a hot day and travels in her mind far, far into the cosmos — all the way to the moon.

Many of Lempel’s protagonists are seemingly happiest, or most deeply themselves, when working in nature. A Brooklyn woman named Pachysandra tends the small plot of earth next to her apartment building and feels herself transported back to her home in South Carolina — “The rise and fall of her green days pursued her in her dreams.” Mrs. Zagretti lovingly plants a delicate fig tree in her yard on Long Island and proudly presents its fruits to her Jewish neighbor as an antidote to American consumerism.

Connections between humans and animals — even insects — are particularly powerful. In the title story in our collection, the squirrels in the zoo come running at the approach of their blind friend Danny. Mrs. Zagretti finds a soulmate in a housefly, eliciting a devastating reaction from her Jewish neighbor. Mrs. Zagretti is not the only character to feel a powerful tie with a fly, either: the protagonist of a different story tries to keep a fly alive in her apartment by feeding and speaking to it — when it lands on a mirror, she takes note of how it communes with its reflection. In yet another story, a resident of an old age home releases a fly into the world in hopes that it will “live out its life in joy and satisfaction.”

Far from serving as a gentle pastoral backdrop, nature is often the site of grave danger, where beauty is intertwined with menace. A young woman hiding in the forest remembers that “the wind brought me the smell of berries, a dead bird, the rotten carcass of a half-devoured creature.” The half-mad narrator of another story calls the flowers in her garden by the names of people who perished in the Holocaust. Each burns as a memorial candle in its particular season. “Soaking up hot sunshine and plenteous rain, hail and hurricane, they know the art of adaptation and survival,” just like the survivor who watches over them.

Far from serving as a gentle pastoral backdrop, nature is often the site of grave danger, where beauty is intertwined with menace. A young woman hiding in the forest remembers that “the wind brought me the smell of berries, a dead bird, the rotten carcass of a half-devoured creature.” The half-mad narrator of another story calls the flowers in her garden by the names of people who perished in the Holocaust. Each burns as a memorial candle in its particular season. “Soaking up hot sunshine and plenteous rain, hail and hurricane, they know the art of adaptation and survival,” just like the survivor who watches over them.

For Lempel, the boundaries between dream and reality, civilization and nature, human and animal are permeable, shifting, difficult to trace. Her evocation of the natural world gives her stories a weight more powerful than the trajectory of her plots, and the precision and musicality of her prose offer exceptional pleasure to the reader.

So much for the “unbridgeable divide” between Yiddish and nature.

Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub received the Yiddish Book Center’s 2012 Translation Prize for their work on the fiction of Blume Lempel, now available to English readers in their collection Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories.

Related Content:

- Joanna Rakoff: The Smell of Old England

- Michael Idov: The Act of Self-Translation

- Jerome Cheryn: Back to the Bronx