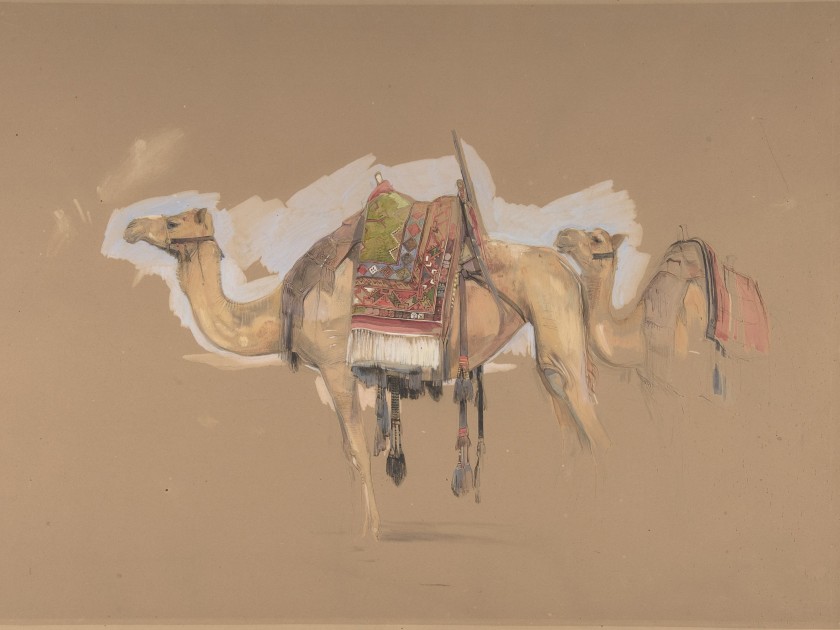

Two Camels, John Frederick Lewis, 1843

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anonymous Gift, 1961

When readers ask if I enjoy writing historical novels, one of the first things I always tell them is that the research is the fun part, writing the book is hard work. That was certainly the case for The Midwives’ Escape: from Egypt to Jericho.

There were so many interesting pieces of history to learn! For example, unlike most ancient cultures where men married more than one woman, in Lagash (modern-day Iraq) the custom was that a woman could marry more than one husband — as long as they were brothers. Of course I put that situation in my novel.

I had already learned a great deal about medieval midwifery while writing Rashi’s Daughters, so I decided to put that knowledge to use by making my Egyptian mother and daughter heroines midwives. I couldn’t resist naming them after the famous Egyptian midwives from Exodus 1:15. But I still had to research ancient midwifery to ensure that my midwives stayed in character. To my surprise, and delight, I learned that ancient Egyptian midwives utilized bronze forceps to pull out a baby wedged in the mother’s birth canal (a procedure I endured with my first child’s birth). So I made sure to write a scene that included the technique and, to show my older heroine’s expertise, I included a breech birth scene. They also knew what herbs brought on an abortion, and so I mention that as well.

Yet my midwife characters were by necessity healers. According to Numbers and Deuteronomy, Israelites were involved in a series of wars with various Canaanite armies while conquering the Promised Land. But I didn’t want to describe every conflict the Torah mentions, so I only detailed battles with the Israelites’ most well-known adversaries: Amalek and Bashan. Which meant learning about ancient weapons, various combat strategies, and common injuries. I turned to novels featuring soldiers for some of this background work and I was impressed by novels about ancient wars such as Harry Sidebottom’s Warrior of Rome and Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles.

In use were swords, shields, javelins, chariots, and bows and arrows. And a popular weapon was the sling — think David and Goliath. There are ancient paintings of soldiers that show slingers riding in chariots or walking beside them, their slings hanging from their belts. Used by shepherds and goat herders to keep carnivores away from their flocks, slings were relatively simple and inexpensive to make. And their ammunition — stones — was readily available and free.

Since my main characters were going to be women from the mixed multitude (non-Israelites) who left Egypt with the Israelites, the first thing I had to determine was who the mixed multitude were. Thankfully Los Angeles has many religious research libraries, including those at Hebrew Union College (HUC), American Jewish University (AJU), and Loyola-Marymount University (LMU), which is within walking distance of my house.

Early on, I found out that ancient Egypt had trade relations with many countries prior to 1700 BCE, especially with the Hittites from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). In between their own wars, these men were formidable mercenaries, some serving in Egypt. I was familiar with Hittites from the Bible story of David and Bathsheba (wife of Uriah the Hittite). Since I knew my novel would feature soldiers, (in particular I had been thinking of foreign ones, who could then train the fleeing Israelite slaves) Hittites were a logical choice. With a focus on women, I included Nubians, also known as Cushites, famous for their female equestrian-archers. This allowed me to introduce a specific Cushite who would marry Moses, much to Miriam and Aaron’s disapproval.

Was this a miracle? Maybe, it depends on whom you ask.

I learned about the Bronze Age Collapse at the end of twelfth century BCE, which caused many Mediterranean locales, such as Troy, Lebanon, Canaan, Syria, Cyprus, Lagash, Anatolia, Crete, and more to suffer drought and famine. Biblical scholars posit that this was when Jacob’s family left Canaan for Egypt, along with other starving peoples who later became part of the mixed multitude.

Not surprisingly, modern Bible scholars are skeptical of the version of history presented in the Torah, preferring to call it legend. Of course, six million Israelites didn’t escape Egypt; the entire Egyptian population was barely six million. Still, I couldn’t ignore all the miracles described in Exodus, such as the manna appearing in the desert just as food is running out, or the pillar of fire that kept the Egyptian army at bay all night. And how did so many people cross the Sea of Reeds, if not by a miracle?

I recalled a college astronomy class where I learned how tides are affected by the moon and sun. When the sun, moon, and Earth are in alignment (at a new or full moon), solar tides have an additive effect on lunar tides, creating extra high, high tides, and very low, low tides. During the vernal and autumnal equinoxes (March 21 and September 23, respectively) the sun is positioned directly above the equator, causing even higher high tides and lower low tides.

I found myself considering when Israelites observed the first Passover. In narrow low-lying wetlands, such as the Sea of Reeds, people could walk on crushed reeds during low tide, but the high tide would be over fifteen feet at its height, deep enough to drown heavily armored Egyptians and horses. But if the Israelites, and the mixed multitude, left one side of the shore and arrived at the other during high tide, especially when the east wind blew, they would be at the deepest water during the lowest tide and thus able to walk through it.

Was this a miracle? Maybe, it depends on whom you ask.

For those readers who want to delve deeper into this topic, I highly recommend The Exodus: How it Happened and Why it Matters by Richard Elliott Friedman.

And for readers who want to explore the rich world of ancient Egypt, I hope you’ll read my new book, The Midwives’ Escape: from Egypt to Jericho.

The Midwives’ Escape: from Egypt to Jericho by Maggie Anton

Maggie Anton is an award-winning author of historical fiction, as well as a Talmud scholar with expertise in Jewish women’s history. Intrigued that the great Jewish scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, she researched the family and their community. Thus the award-winning trilogy, Rashi’s Daughters, was born. Since 2005, Anton has lectured about the research behind her seven books at hundreds of venues throughout North America, Europe and Israel.