Notebooks housed in the Danish National Museum

The spring I was sixteen, I fractured my neck in a car accident. My best friend and I were on our way to Arizona to spend a week with her grandma; we left Ann Arbor for the Detroit airport before dawn, in a storm. Her mom was driving — we hit a patch of ice and went spinning until another car slammed into the side of ours. I remember the wet, wavy headlights coming toward us, the staggering noise, the flying and falling as we flipped from the road into a ditch. Landing felt like my ribs collapsing, bones compressing into a flattened, agonizing mess. My best friend was crying, and then, in the hideous silence of the backseat after, she asked me if we were dead. We weren’t sure what that was, what this was. There was the not knowing, and her familiar voice: are we dead? The experience of that particular uncertainty — in my body and mind — has stayed with me for thirty years.

My best friend and her mom were okay. I was okay — I broke a good bone, not the one a notch lower, which would have paralyzed me, not the one higher. I can’t remember what they said about that one. I tried not to hear, wanted to keep worse fear and more fear and other fear out. In the months that followed the accident, I wore a neck brace and stayed still. I’m a naturally frenetic person; moments of mandatory stillness are always strange and tricky turns for me. In the brace, I began traveling frantically in my mind. I made up stories that took place elsewhere, anywhere other than in that brace, in my body, in the dread I couldn’t outrun. I had written poetry forever already — terrible rhyming doggerel about high-school athletes I was in a rotation of dating and breaking up with. But something about the way the weeks stretched out as my neck healed made me seek a longer form of order.

Having thought I might be dead, I suddenly knew, in the way that we can know for a bit after horror befalls us, that it, whatever it may be, can in fact happen. And will. There are those who live with this fear all the time, and when I first felt it, I also first imagined what it might be to feel this way constantly, forever. My terror was too vast and amorphous to be examined or ordered by way of any short form. So I wrote, by hand, in composition notebooks, a romantic novel. It had no car accident in it, was set in China (where I had spent childhood summers), was definitely terrible, and gave me a beautiful escape. I can still see the way those lined pages looked, full of words, the only control I could take.

I can still see the way those lined pages looked, full of words, the only control I could take.

The chilly feeling of the accident has come back to me, pinned as I am, as we all are, by the plague and by fear for the world. There is a colorful, sharp aspect to the way everything looks, and I’m trying to write my way out of my mind. How, this time? What connection is there between the shapes our projects take and our particular states of disarray? I write across the genre range (fiction, non-fiction, and poetry), and have spent this unrecognizable Spring percolating the organizing power of art and the question of what form might best contain this difficulty. The neck brace days gave a daunting but long view, one of linked chapters. Over four months of lockdown, I’ve written exclusively sonnets. Their rules are so tidy, constraints so stable. Rhyming lines and blocky stanzas feel orderly. I am responsible for inventing only what fits inside those compact units. Iambic pentameter echoes conversation; by honoring the natural cadence of speech, iambs create a lovely counterpoint to harrowing content: terror, sterilization, violence, beloved people dying alone, all of us needing to be kept apart in order to keep each other safe.

Maybe the coming months will change where we are, and call for something longer than three stanzas and a couplet, let me unbuckle the seatbelt of iambic pentameter. Maybe not. I keep thinking of James Baldwin’s description of the difference between preaching and writing: “When you are standing in the pulpit, you must sound as though you know what you’re talking about. When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway.”

Our abilities to live, feel, and think all require an almost fearful wonder, a compulsion to discover what we don’t know.

What will so much uncertainty and disorder mean for writers? The freshness of this new and complex context, however awful, might give us a view of ourselves that is at once different and distant, a potentially productive shock. Our abilities to live, feel, and think all require an almost fearful wonder, a compulsion to discover what we don’t know. And, as Baldwin brilliantly suggests, may not want to know.

There is so much I don’t want to know, and yet I keep flickering over the macro and micro suffering again and again. I’m desperate to look away, but can’t possibly avert my eyes. This contradiction is common, I know, human, and not surprising; I’ve felt sickening versions of it many times before. How do we ask — ourselves and one another — about the relentless murder of Black Americans; about what’s happening at our borders; about countries we’ve devastated; about children imprisoned in detention facilities; about countless atrocities? How do we understand a global pandemic? What do hundreds of thousands of deaths look like?

Literature gives us a way to look closely, to do the work of imagining unbearable suffering, our own, and everyone else’s. Living in the syntax, imaginations, and stories of people other than ourselves, we get to inhabit their lives fully and privately. And this changes us. As Virginia Woolf puts it, books “split us into two parts as we read,” because “the state of reading consists in the complete elimination of the ego,” as well as “perpetual union with another mind.”

Literature gives us a way to look closely, to do the work of imagining unbearable suffering, our own, and everyone else’s. Living in the syntax, imaginations, and stories of people other than ourselves, we get to inhabit their lives fully and privately.

This is a reader meeting a writer, but we can also feel it as a division of ourselves as writers, into more minds than one — in a good way. Fiction is a ticket to fleeing our limitations (whether physical or psychological), connecting even with characters we might disdain, fear, or fear becoming. Reading and writing put us in other people’s interiors, give us the beauty of neatly made language, and the expression of what we knew in our own marrow to be true, but couldn’t yet articulate. Toni Morrison gave us Pecola Breedlove in The Bluest Eye, and like most women of my generation, I grew up feeling Pecola was real, that I knew her, and had access to her longing. How else, other than living in their pages, could we have learned the empathy that knowing the Breedloves taught? There’s no way.

When the boundaries between self and other dissolve, it’s possible to realize how many people have felt whatever it is we are feeling, no matter how novel each pain seems. James Baldwin said in an interview in Life Magazine: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dickens and Dostoevsky that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.”

Recently, my supremely thoughtful students at the University of Chicago asked a series of questions about anguish in the lives of writers, whether we need to be tragic, tormented. I was glad to be old enough to tell them (truthfully): I don’t think so. Instead, writing can be a place where we quarantine our worst fears and impulses, finding the right container for each darkness: an adolescent novel to measure the months it took to get my bones back together; sonnets to organize an examination of what I don’t want to know (but must find out).

Of course we all create and tell stories in countless ways and spaces: details of our days we shape as a way to make them meaningful and manageable; our memories and dreams we repeat to assess what they mean (and who they make us); our loves and triumphs we mark; and our tragedies we write, speak, and repeat to endure. Narratives we know — books and poems we remember forever — are templates for our own expressions. The most vulnerable among us are often robbed of the possibility of telling their stories, getting to define themselves.

The most vulnerable among us are often robbed of the possibility of telling their stories, getting to define themselves.

But every human being needs a say, and a way to listen to, see, and imagine perspectives that are not our own. This is why we create and read fictional characters, to know them, to practice, to expand into multiple versions of our best and worst selves. This seems an especially important exercise with people we don’t know at all, those whose experiences feel impossibly different from ours.

My favorite expression is the Chinese jingdi zhiwa, a frog in a well who looks up and thinks it can see all of heaven, but is actually seeing only a little circle of the sky. The frog needs to leave the well in order to see the world or understand anything about her place in it. Sometimes fear is a well; sorrow, too. Genre can be a well.

I often can’t see my projects without leaving them, which requires working on opposing projects: moving from an historical war novel to a slim poem, from a screenplay with the strictest possible economy back to luxurious prose. Then, from the outside, I can see what’s happening in the project I fled, and fix what wasn’t working, what I couldn’t see coherently from the inside. Will this moment of standing outside of our lives allow for new clarity about what’s around us, and about ourselves, reinvented?

This shared terror is an awful version of a primary experience of newness. Our days and activities are changed and unusual; our teaching, thinking, and writing all suddenly require reinvention. Having lost our familiar reference points, we must reimagine ourselves. When I can be cheerful about it, this challenge reminds me of the power of reading.

Certain questions may be best asked by particular genres. For me, those requiring precision and an economy of glittering efficiency tend to be poems. When the margins allow for an epic sweep and scope, or I’m trapped in a brace, I make a novel. Sometimes (like this moment, writing this), a core truth begs to be expressed by way of the frankness of nonfiction. Genre is a boundary best blurred, writing as shape-shifting as the infinite questions we have to ask ourselves and one another. These days, diminishing boundaries feel a lot like hope, revealing multiple ways to reach out across expanses threatening to distance us for real.

Genre is a boundary best blurred, writing as shape-shifting as the infinite questions we have to ask ourselves and one another.

Every night in Chicago’s south loop, need drives thousands of us to our windows and balconies to flash lights, sing, wave, and say: I see you. Sometimes, in the circles of light, I catch sight of those headlights coming from my memory of the accident; other times I see starlight, disco balls, sparklers. Watching and listening, I try to control my own nouns, to keep intact times I’ve danced, celebrated, lived.

We were not dead. I’m trying to remember how I responded to my best friend’s question that day in the crushed car: I don’t think so? I don’t know? I hope I said I love you. The truth is, I can’t remember.

So maybe this not-sonnet is a letter back to the 1980’s, or forward to an era when we’re all out of this brace. As changeable as our projects, we’ll morph with them, because asking, imagining, and understanding are synchronized tasks. I am young again in my mind now, my own first reader, waiting to find out what happens next. Hoping to transmit, too, to anyone who wants to keep me company. And to hear and read you back, always on receive.

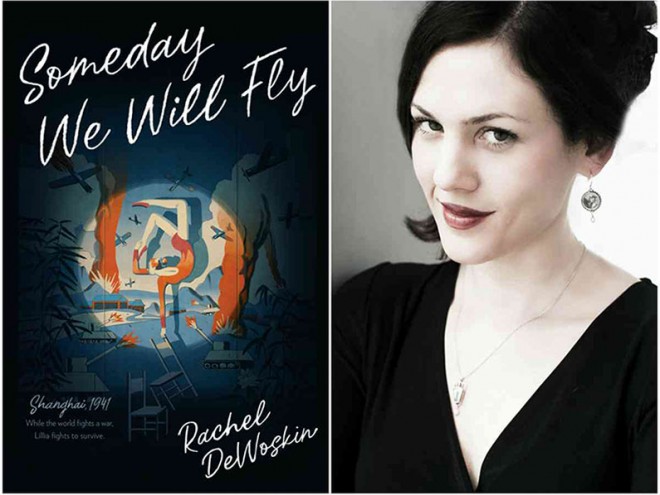

Rachel DeWoskin is the award-winning author of five novels: Banshee; Someday We Will Fly; Blind; Big Girl Small, and Repeat After Me; and the memoir Foreign Babes in Beijing, about the years she spent in Beijing as the unlikely star of a Chinese soap opera. Her poetry collection, Two Menus, was published by the University of Chicago Press in May of 2020, and she has Hollywood development deals for Foreign Babes in Beijing and Banshee. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and numerous journals and anthologies. She’s an Associate Professor of Practice at UChicago and an affiliated faculty member in Jewish and East Asian Studies.