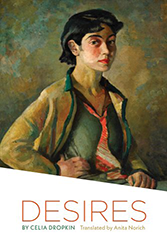

Roza, wife of Leyzer ben Moses Judah, Title Page of the Register of a Jewish Midwife. Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam.

One of the primary goals of The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization is to open the entirety of Jewish culture, including many overlooked voices, to English language readers. Among the many voices we include in Volume 6: Confronting Modernity, 1750 — 1880 are those of Jewish women, across class, professional, and ethnic lines. Each discovery brought new excitement. What we thought of as lost and silenced traces of lives suddenly appeared in overlooked sources. The role of Jewish midwives as respected and necessary medical experts, participants in ritual law, and writers who learned to shape their records and experiences in their own voices, exemplifies the volume’s inclusive vision. A small excerpt from the register of a Jewish midwife appears in the volume (vol. 6, p. 22). Jordan Katz’s masterful doctoral dissertation explored the midwives’ role in much greater depth, as her essay below demonstrates.

-Elisheva Carlebach, editor of The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, Volume 6

As a historian of premodern Jewish life, it can be difficult to find women’s voices in the sources. It’s not that Jewish women were absent, it’s just that they didn’t write often — or, at least, not nearly as much as men. So you can imagine my surprise when, as I sat down to read rabbinic sources about eighteenth-century communal life, I found a trove of information about a group of professional Jewish women, seldom considered: midwives.

While rabbinic sources are often mined for data on the development of halakha (Jewish law), I discovered numerous cases in which rabbis relied on the expert medical opinions of midwives to resolve their halakhic questions. This adds a new dimension to our understanding of how we can use rabbinic materials to get at the history of Jewish women in the early modern period (1750 to 1880).

From these sources, it becomes clear that midwives had far more experience with questions of women’s bodies than rabbis themselves did. In many instances, rabbis considered their judgments more reliable than those of (male) physicians.Midwives knew about women’s diseases, postpartum conditions, and self-inspections of their bodies; midwives supplied information to rabbis regarding women’s sexuality, their ailments, and their material gynecological practices — all central components of Jewish law.

Once I was aware of Jewish midwives, it became almost impossible not to see them. I began to locate them in all kinds of early modern European sources. They appeared in Jewish communal sources, where they negotiated their salaries, assumed responsibility for delivering the children of poor women, and testified that certain children were born out of wedlock. They appear in notarial records to certify their contracts, or as witnesses to extramarital affairs or violent rapes.

Some Jewish midwives even commissioned translations of medical handbooks into Yiddish, as did Rachel Salomons of Amsterdam. In 1709, she hired a local translator to change a midwifery treatise from Dutch to Yiddish, so she could read the work in her native language, “So that she will not need to observe any other midwife.” This book was likely part of her training, alongside an apprenticeship with an experienced midwife, which was completed with both Jewish and Christian midwives.

Some Jewish midwives even commissioned translations of medical handbooks into Yiddish, as did Rachel Salomons of Amsterdam.

This range of sources shows that by virtue of their gender, Jewish midwives were privy to sensitive information and able to serve as communal functionaries in a manner not typically afforded to other women during this period. They found themselves at the nexus between municipal and Jewish communal authorities, frequently navigating the competing aims of these systems. Within their communities, Jewish midwives were able to uniquely traverse boundaries; they moved between genders, religious communities, classes, and various ethnic communities within the Jewish world.

Perhaps one of the most significant ways that Jewish midwives contributed to early modern life was by keeping records, and thus allowing us for the first time to hear their own voices, unmediated by men. They participated in a burst of record-keeping in the early modern period. Jewish communities began to keep written communications of all sorts of occurrences in daily life, ranging from financial disputes between community members, to the appointment of rabbis.

Midwives, for their part, assumed responsibility for a different type of record keeping: birth records. Mirroring municipal efforts to document population growth, Jewish midwives began to keep track of the deliveries they attended.They documented this information in personal registers that included details about the child’s sex, birthdate (according to the Jewish calendar), parentage, and, in some instances, where the birth took place. Many of these entries mentioned only the identity of the father, while the mother’s name remained a mystery — unless the child was born to an unmarried woman. By verifying these births and tracking family lineages, including illegitimate children, Jewish midwives became agents of bureaucratic control and communal authority.

Perhaps one of the most significant ways that Jewish midwives contributed to early modern life was by keeping records, and thus allowing us for the first time to hear their own voices, unmediated by men.

As far as we know, these birth registers were the only extant records systematically composed by Jewish women during this period. I found in my research that over the course of the eighteenth century, midwives began to play with different ways of maintaining these records, incorporating various pieces of information as needed. As a result, midwives’ records from the early eighteenth century included some details that one might not expect to find in a vital record, such as the identification of clients solely through the person whose home they resided in, or by the baked goods they peddled on the street. Only by the end of the century were such records consolidated into a recognizable format.

By the time the midwife Roza bas Yukel of Groningen, Netherlands, sat down to record her deliveries in 1794, she was able to express in her own words what she perceived as the purpose of her register. On the title page, she composed a dual-language introduction, penned both in Yiddish and in Hebrew:

This is the book of the generations/children of man, those that were born by my hands among the Hebrew women. I. came to them, I the midwife, for they are vital [Exodus 1:15 – 19] and give birth to a son or daughter. I took this book as my possession, and I recorded in the name of those giving birth with the name of the newborn, with the date of birth, so that it should be a remembrance from the day I began this occupation and forward. And I prayed to the Lord above that he should strengthen me and give me courage and not let my hands falter while I am engaged in this profession, and may no obstruction be caused by my hands, heaven forbid, neither to the woman sitting on the birthing stool nor to the newborn about to be born: Only let it be expelled from the uterus like an egg from a hen.

This expression of purpose is unique to Roza’s register. Records from earlier midwives bear no such introductions or lyrical openings. Despite this, they embraced the same purpose: to serve as aides-mémoires through which to document the evolving population of the Jewish community in each locale; for the midwives themselves, for the women giving birth, and for the Jewish community at-large.

Jordan Katz completed her PhD in History at Columbia University. In the fall, she will begin a postdoctoral fellowship in the Judaic Studies Program at Yale.